-

1 Introduction

Emergency responders are important for the safety of society by reducing the risk of crimes, deaths and diseases, as they are tasked with not only monitoring compliance with regulations (e.g. police officers), but also providing assistance and (health) care (e.g. emergency medical workers and firefighters). Because they are often sent to the front line, this group of professionals has specific risks of experiencing trauma while performing their duties.1x D.S. Weiss, A. Brunet, S.R. Best, T.J. Metzler, A. Liberman, N. Pole, J.A. Fagan & C.R. Marmar, ‘Frequency and Severity Approaches to Indexing Exposure to Trauma: The Critical Incident History Questionnaire for Police Officers’, 23 Journal of Traumatic Stress 734 (2010). One of these traumatic experiences is experiencing violence at work, directed towards the professionals. Studies have shown that law enforcement officers and workers in (health) care have an increased risk of experiencing workplace violence in various countries, such as in the UK,2x See ‘Violence at Work’, available at: <www.hse.gov.uk/Statistics/causinj/violence/index.htm> (last visited 23 March 2016). the USA3x D.M. Gates, C.S. Ross & L. McQueen, ‘Violence against Emergency Department Workers’, 31 The Journal of Emergency Medicine 331 (2006); C.E. Rabe-Hemp and A.M. Schuck, ‘Violence against Police Officers’, 10 Police Quarterly 411 (2007). and the Netherlands.4x J. Naeye and R. Bleijendaal, Agressie en geweld tegen politiemensen [Aggression and violence directed at police] (2008).

Studies have shown that experiencing workplace violence may have several, potentially severe, consequences. For example studies suggest that experiencing workplace violence may result in increased feelings of distress,5x T.M. Leino, R. Selin, H. Summala & M. Virtanen, ‘Violence and Psychological Distress among Police Officers and Security Guards’, 61 Occupational Medicine 400 (2011). emotional exhaustion and burnout symptoms,6x M. Bernaldo-De-Quiros, A.T. Piccini, M.M. Gomez & J.C. Cerdeira, ‘Psychological Consequences of Aggression in Pre-hospital Emergency Care: Cross Sectional Survey’, 52 International Journal of Nursing Studies 260 (2015). insecurity,7x L. Middelhoven and F. Driessen, Geweld tegen werknemers in de openbare ruimte [Violence against Employees in the (Semi-)Public Space] (2001). sickness notifications, turnover intentions,8x M. Abraham, S. Flight & W. Roorda, Agressie en geweld tegen werknemers met een publieke taak [Aggression and Violence against Employees with a Public Task] (2011), at 36. and injuries or even death of professionals,9x See ‘About Law Enforcement Officers Killed and Assaulted, 2013’, available at: <www.fbi.gov/about-us/cjis/ucr/leoka/2013> (last visited 22 September 2015). which were found also in other populations who experience workplace violence.10x A.A. Grandey, J.H. Hern & M.R. Frone, ‘Verbal Abuse from Outsiders versus Insiders: Comparing Frequency, Impact on Emotional Exhaustion, and the Role of Emotional Labor’, 12 Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 63 (2007); M.T. Sliter, S.Y. Pui, K.A. Sliter & S.M. Jex, ‘The Differential Effects of Interpersonal Conflict from Customers and Coworkers: Trait Anger as a Moderator’, 16 Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 424 (2011). It should be noted that studies on workplace violence rarely have a longitudinal design, measuring violence and characteristics over time, and it is thus possible that some of these characteristics were present before experiencing workplace violence and were not a result from experiencing workplace violence. However, the longitudinal studies that were available suggest that professionals may suffer from psychological consequences after experiencing workplace violence.11x Id. Thus, workplace violence against emergency responders can affect professionals and organisations.

Therefore, reducing workplace violence of emergency responders is a priority for the political agenda in many countries.12x Eurofound, Physical and Psychological Violence at the Workplace (2013). In the Netherlands, this is reflected by the programme of the Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations that has been set up to prevent aggression and violence against ‘public sector professionals’, who work for the public interest, work in public services and work for or on behalf of a public body. Measures that have been taken to prevent workplace violence against public sector professionals are encouraging organisations to communicate which behaviours of citizens are and are not acceptable, and to provide training to professionals.13x Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations, Handreiking agressie en geweld [Guide to Aggression and Violence] (2011). In addition, the maximum sentence demanded for violent offenders may be raised up to three times the regular maximum sentence if the victim is a public sector professional.14x See ‘Geweld tegen werknemers met publieke taak’, available at: <www.rijksoverheid.nl/onderwerpen/geweld-tegen-werknemers-met-publieke-taak/inhoud/aanpak-geweld-tegen-werknemers-met-publieke-taak> (last visited 22 September 2015).

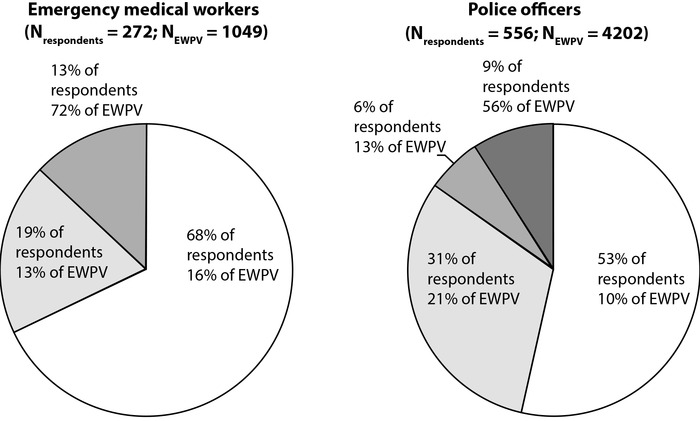

While all high-risk professions may frequently experience violence, it has been widely shown in general victimisation studies that experiencing violence is not equally distributed. Having experienced victimisation has often been found to be the strongest correlate of subsequent experiences of violence or other crimes, for many populations,15x See e.g. K.H. Breitenbecher, ‘Sexual Revictimization among Women. A Review of the Literature Focusing on Empirical Investigations’, 6 Aggression and Violent Behavior 415 (2001); G. Farrell and A.C. Bouloukos, ‘International Overview: A Cross-National Comparison of Rates of Repeat Victimization’, 12 Crime Prevention Studies 5 (2001). including professionals at work.16x L. van Reemst, T.F.C. Fischer & B.W.C. Zwirs, Geweld tegen de politie: De rol van mentale processen van de politieambtenaar [Violence against the Police: The Role of Mental Processes of the Police Officer] (2013). According to survey studies, some professionals experience workplace violence relatively often and others experience relatively little workplace violence.17x It is important to note that victimisation, as measured in self-report victimisation surveys, is probably a combination of the actual frequency of victimisation and how likely it is that people report this victimisation in a survey (e.g. based on to what extent they remember the incidence or experienced harm from the victimisation incidence). This is often considered a limitation of victimisation surveys, as it does not allow the separation of actual and perceived victimisation. However, if we are interested in decreasing experiences of victimisation, this combination of frequency and remembrance or harm of victimisation could be considered our concept of interest in victimisation studies. This unequal distribution is related to the profession of people, but victimisation experiences are also unequally distributed within specific professions.18x Abraham et al. (2011), above n. 8; A. Ettema and R. Bleijendaal, Slachtofferprofielen [Victim Profiles] (2010); T.F.C. Fischer and L. Van Reemst, Slachtofferschap in de publieke taak [Victimisation in the Public Task] (2014). The unequal distribution within professions will be illustrated by a figure that was derived from the study of Fischer and Van Reemst.19x Fischer and Van Reemst, above n. 18. The study was based on data from the Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations, who have monitored workplace violence in the public sector in the Netherlands. In this study, latent class analyses were used to identify categories of self-reported victimisation of workplace violence (verbal, physical, intimidation, sexual and discrimination), in the past year, of emergency medical workers (N = 272, who experienced 1,049 workplace violence incidences in total), police officers (N = 556, who experienced 4,202 incidences in total) and other employees (excluding firefighters).

As can be seen in Figure 1, a relatively large percentage of professionals experienced only a small percentage of total workplace violence incidences, whereas a small percentage of professionals experienced a high percentage of total workplace violence incidences. For emergency medical workers, a group of only 13% of professionals reported 72% of all workplace violence incidences, and for police officers, 9% of professionals reported 56% of incidences. The results of this study suggest that, also within specific professions, some professionals experience more workplace violence than others.

Overall, the differences in experiencing workplace violence raise the following question: which characteristics of professionals are related to experiencing more external workplace violence within professions, and to what extent? This knowledge is needed to reduce external workplace violence in the future and to provide directions for future studies. This paper will present a theoretical framework to study variations in workplace violence experienced by emergency responders, by applying and integrating criminological theories that have been used in victimology, and highlighting empirical applications and ethical dilemmas related to the theories. Thereby, in this paper, differences in victimisation are explained using the victim’s perspective.Distribution of incidences of EWPV of emergency medical workers and police officers, based on Fischer and Van Reemst. With permission from Fischer and Van Reemst, above n. 18. For detailed information about the categories, see the publication.

With permission from Fischer and Van Reemst, above n. 18. For detailed information about the categories, see the publication.

This paper makes contributions to the literature on theory development of workplace violence against emergency responders: as studies about workplace violence against emergency responders are often published in journals focusing on practitioners in (pre-hospital) emergency care,20x See e.g. C.C. Mechem, E.T. Dickinson, F.S. Shofer & D. Jaslow, ‘Injuries from Assaults on Paramedics and Firefighters in an Urban Emergency Medical Services System’, 6 Prehospital Emergency Care 396 (2002); S. Koritsas, M. Boyle & J. Coles, ‘Factors Associated with Workplace Violence in Paramedics’, 24 Prehospital and Disaster Management 417 (2009). studies are often limited in their theoretical foundations. Therefore, classic victimisation theories have rarely been applied to workplace violence against emergency responders.21x Some examples in other populations: T.F.C. Fischer, L. van Reemst & J. de Jong, ‘Workplace Aggression Toward Local Government Employees: Target Characteristics’, International Journal of Public Sector Management (2016); S. Landau and Y. Bendalak, ‘Personnel Exposure to Violence in Hospital Emergency Wards: A Routine Activity Approach’, 34 Aggressive Behavior 88 (2008); F. van Mierlo and S. Bogaerts, ‘Vulnerability Factors in the Explanation of Workplace Aggression’, 11 The Journal of Forensic Psychology Practice 265 (2011). Applying victimological theories helps us to identify and categorise possible ‘risk factors’ of workplace violence, and integrating theories helps us to explain workplace victimisation better. Applying victimological theories seems justified because we can consider professionals who experience workplace aggression and violence as ‘victims’, even though definitions of victims differ and the word is subject to stigma (or at least related to concepts such as suffering, passivity and forgiveness).22x J. van Dijk, ‘Free the Victim: A Critique of the Western Conception of Victimhood’, 16 International Review of Victimology 1 (2009).

In this paper, first, the context of workplace violence against emergency responders will be described, including the function of emergency responders, and the nature and extent of workplace violence against emergency responders. Second, criminal opportunity theories and personal vulnerability notions (originating from the victim precipitation theory) will be applied to experiencing workplace violence. These two victimological perspectives address the role of situational and victim characteristics in victimisation. The results from studies about correlates of workplace violence of emergency responders will be described in relation to these theories, and arising opportunities for future research will be described. Lastly, I will reflect on ‘victim blaming’, which is an ethical topic related to studying differences in workplace violence and provides a direction for future research about workplace violence against emergency responders. -

2 Role and Function of Emergency Responders

The three groups of professionals working as emergency responders (police officers, firefighters and emergency medical workers) share many common work circumstances because they all respond to emergencies and are needed for public safety. Emergency respondents’ work also requires fitness of the professionals and has physical demands.23x See also S.N. Kales, A.J. Tsismenakis, C. Zhang & E.S. Soteriades, ‘Blood Pressure in Firefighters, Police Officers, and Other Emergency Responders’, 22 American Journal of Hypertension 11 (2009). All emergency responders are thought to have a relatively high risk of experiencing violence at work, because of the frequent contact with citizens (or patients, family or bystanders), the negative emotions and frustrations an emergency may cause to these citizens and the broad variety of citizens they deal with, including citizens who are more likely to be offenders, such as people who are under the influence of alcohol or drugs or have a mental illness.24x See e.g. M.M. LeBlanc and E.K. Kelloway, ‘Predictors and Outcomes of Workplace Violence and Aggression’, 87 Journal of Applied Psychology 444 (2002).

In addition to these similarities, each profession is unique. Police officers enforce laws and de-escalate (potential) threats, firefighters safeguard people by rescuing or fire extinguishing, and emergency medical workers provide medical care before arriving at the hospital. Although it will not be possible to give an exhaustive list of differences in this paper, I will describe some additional differences between the professions that might influence professional-citizen interactions. First, police officers can legitimately use physical force in interaction with citizens25x See e.g. G.P. Alpert, R.G. Dunham & J.M. MacDonald, ‘Interactive Police-Citizen Encounters that Result in Force’, 7 Police Quarterly 475 (2004). and can use weapons to do so, such as batons or a service weapon, whereas firefighters and emergency medical workers cannot. Second, firefighters leave for an emergency with more professionals than police officers and emergency medical workers. Third, the frequency of contact of citizens varies between professions, with police officers having the most and firefighters having the least contact with citizens. Police officers may remain outside even if no emergency calls were received, whereas many firefighters work as volunteers and only work if a call was received. Lastly, in severe or complex emergencies, the three professions may work together, each having their own work task. These differences in work situations may cause differences in professional-citizen interactions and experienced workplace violence (EWPV).26x Similar to other occupations. For example studies in the general health care sector have indicated that different occupations may result in differences in EWPV and correlates of EWPV. E. Viitasara, M. Sverke & E. Menckel, ‘Multiple Risk Factors for Violence to Seven Occupational Groups in the Swedish Caring Sector’, 58 Industrial Relations 202 (2003); S. Winstanley and R. Whittington, ‘Violence in a General Hospital: Comparison of Assailant and Other Assault-Related Factors on Accident and Emergency and Inpatient Wards’, 106 Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 144 (2002). However, because of their similarities, all have a heightened risk of experiencing workplace victimisation. Therefore, it is important to study workplace violence in this population. -

3 Nature and Extent of Workplace Violence against Emergency Responders

In studies, the act of violence and aggression against professionals is often referred to as ‘workplace aggression’ or ‘workplace violence’. Schat and Frone’s definition of workplace violence is ‘behaviour that a target wants to avoid, takes place in a work-related situation, and is potentially physically or psychologically damaging to the target’.27x A.C.H. Schat and M.R. Frone, ‘Exposure to Psychological Aggression at Work and Job Performance: The Mediating Role of Job Attitudes and Personal Health’, 25 Work & Stress 23 (2011); K.E. Dupre, K.A. Dawe & J. Barling, ‘Harm to Those Who Serve: Effects of Direct and Vicarious Customer-Initiated Workplace Aggression’, 29 Journal of Interpersonal Violence 1 (2014). ‘Workplace’ thus refers to the type or context of the situation and not the actual location, and it can occur in public space, for example. Regarding the nature of external workplace violence, studies have shown that workplace violence can take physical and psychological shapes. This includes being hit, punched and grabbed (physical), being yelled at and being called names (psychological). Threats are sometimes studied as a separate type (or included in the definition of psychological workplace violence), as are sexual harassment and being discriminated against. Overall, types of workplace violence that have been addressed in studies have varied greatly.28x J. Barling, K.E. Dupre & E.K. Kelloway, ‘Predicting Workplace Aggression and Violence’, 60 Annual Review of Psychology 671 (2009).

In this paper, I focus on external workplace victimisation. I will not focus on internal workplace violence, which is violence initiated by an individual within the organisation, for example bullying or assault between workers or between a supervisor and a worker, and is more often the focus of research.29x K. Aquino and S. Thau, ‘Workplace Victimization: Aggression from the Target’s Perspective’, 60 Annual Review of Psychology 717 (2009); N.A. Bowling and T.A. Beehr, ‘Workplace Harassment from the Victim’s Perspective: A Theoretical Model and Meta-Analysis’, 91 Journal of Applied Psychology 998 (2006); B.J. Tepper, ‘Abusive Supervision in Work Organizations: Review, Synthesis and Research Agenda’, 33 Journal of Management 261 (2007). External workplace violence occurs more frequently30x B.L. Bigham, J.L. Jensen, W. Tavares, I.R. Drennan, H. Saleem, K.N. Dainty & G. Munro, ‘Paramedic Self-Reported Exposure to Violence in the Emergency Medical Services (EMS) Workplace: A Mixed-Methods Cross-Sectional Survey’, 18 Prehospital Emergency Care 489 (2014). and is a type of workplace violence initiated by people outside the organisation, such as clients, patients, students, suppliers, intruders and citizens in general.31x C. Mayhew and D. Chappell, ‘Workplace Violence: An Overview of Patterns of Risk and the Emotional/Stress Consequences on Targets’, 30 International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 327 (2007); D. Yagil, ‘When the Customer Is Wrong: A Review of Research on Aggression and Sexual Harassment in Service Encounters’, 13 Aggression and Violent Behavior 141 (2008). Specifically, emergency responders most often experience victimisation from people they provide a (safety) service to.32x See e.g. M.M. LeBlanc, K. Dupre & J. Barling, ‘Public-Initiated Violence’, in E. Kelloway, J. Barling & J. Hurrell (eds.), Handbook of Workplace Violence (2006) 261.

The extent of external workplace violence varies depending on the definition of workplace violence. For example, in 2011, the monitor of the Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations of the Netherlands studied the extent of EWPV in many public sector employees. Their conceptualisation of workplace violence included five types of behaviour: verbal aggression (including name-calling and yelling), physical aggression (including pushing and hitting), threats and intimidation (including threatening of family members and stalking), sexual intimidation (including sexual harassment and rape) and discrimination (including negative comments about skin colour, age or sexual preference). The results of their study indicates that 68% to 73% of police officers, 79% to 89% of emergency medical workers and 44% to 48% of firefighters reported experiencing external workplace violence in the previous year.33x Abraham et al. (2011), above n. 8, at 29. It should be noted that, in their research, police officers who work in other departments, including those who work mostly behind desks were included, which suggests that the percentage of police officers who experienced workplace violence among those who respond to emergency calls might be higher. Studies have suggested that emergency responders most commonly experience psychological workplace violence, followed by physical (and sexual) workplace violence.34x See e.g. Bigham et al., above n. 30. -

4 Explaining Variations in Workplace Violence against Emergency Responders

Victimisation is generally considered to be an interaction between the offender and victim. From the victim’s perspective, characteristics that could influence the likelihood of becoming a victim of external workplace violence are based on the situation the victim is in (including to what extent they are in contact with possible offenders) or on the individual victim (and how they interact with possible offenders). Important theories, predominantly referring to situational characteristics, are the criminal opportunities, such as the lifestyle/exposure theory,35x M.J. Hindelang, M.R. Gottfredson & J. Garofalo, Victims of Personal Crime: An Empirical Foundation for a Theory of Personal Victimization (1978). and the routine activity theory. These were developed around the same time (late 1970s) and are often used in combination.36x L.E. Cohen and M. Felson, ‘Social Change and Crime Rate Trends: A Routine Activity Approach’, 44 American Sociological Review 588 (1979). Meier and Miethe37x R.F. Meier and T.D. Miethe, ‘Understanding Theories of Criminal Victimization’, 17 Crime and Justice 459 (1993); R.F. Meier and T.D. Miethe, Crime and Its Social Context: Towards an Integrated Theory of Offenders, Victims, and Situations (1994). suggested in their work on victimisation theories that these were the more sophisticated theories compared to previous, more limited, ideas about victimology. I will first explain criminal opportunity theories, after which I will present to what extent these theories have been tested and supported in external workplace violence studies.

4.1 Criminal Opportunity Theories

In a nutshell, criminal opportunity theories claim that people vary in the likelihood of experiencing victimisation because they differ in the activities they perform.38x L.E. Cohen, J.R. Kluegel & K.C. Land, ‘Social Inequality and Predatory Criminal Victimization: An Exposition and Test of a Formal Theory’, 46 American Sociological Review 505 (1981). The lifestyle/exposure theory39x Hindelang et al., above n. 35. tries to explain differences in victimisation risks by focusing on the differences in lifestyle, which could be routine daily activities, work/school or leisure activities. These lifestyles are said to explain the differences in exposure to dangerous time, place and others. Hindelang and colleagues elaborate upon various demographic characteristics that may influence peoples’ risk of victimisation indirectly. Because of shared expectations or structural constraints, socio-demographic characteristics such as gender, age or race may affect people’s lifestyle and thus their risk of victimisation.

The routine activity theory adds that routine activity influences the convergence in time and space of three important elements: a motivated offender, a suitable target and the absence of a capable guardian.40x Cohen and Felson, above n. 36. Although originally the routine activity theory has been developed to explain differences in crime rates instead of victimisation risks, this theory has been applied across units of analysis, including victimisation.41x Meier and Miethe (1993), above n. 37, at 470. This means that victimisation is more likely to occur if an individual is in the presence of a motivated offender, is a suitable target (e.g. has valuable possessions or is ‘attractive’ for other reasons) and lacks guardianship (e.g. lacks safety precautions). For example someone who is present in high crime areas and among (repeat) offenders more often is thought to be more likely to be a victim, than someone who rarely finds him or herself in these situations.

The lifestyle/exposure theory and the routine activity theory have similarities. In both theories, the main focus is on the opportunity to become a victim, provided by their activities and lifestyle, instead of the personal motivations of offenders to commit crime. Because of the similarities in the lifestyle/exposure theory and the routine activity theory, these theories have often been used in combination, as an integrated theory.42x Cohen et al., above n. 38. Overall, the idea that victimisation risks vary because of variations in activities and related socio-demographic characteristics is still dominant in many victimisation studies.43x See e.g. K. Holtfreter, M.D. Reisig & T.C. Pratt, ‘Low Self-Control, Routine Activities, and Fraud Victimization’, 46 Criminology 189 (2008); Landau and Bendalak, above n. 21; T.J. Taylor, A. Freng, F.A. Esbensen & D. Peterson, ‘Youth Gang Membership and Serious Violent Victimization: The Importance of Lifestyles and Routine Activities’, 23 Journal of Interpersonal Violence 1441 (2008); M.S. Tillyer, R. Tillyer, H.V. Miller & R. Pangrac, ‘Reexamining the Correlates of Adolescent Violent Victimization: The Importance of Exposure Guardianship and Target Characteristics’, 26 Journal of Interpersonal Violence 2908 (2011). To test these theories, studies focus on to what extent socio-demographic characteristics of the potential victim and situational characteristics of their activities (routine, work/school or leisure) are related to victimisation. Situational characteristics that could be related to victimisation of professionals are characteristics related to the time and place of peoples’ activities, such as the type of work they do, how often, when and where they work, and the type of citizens they work with.4.2 Criminal Opportunity Theories and External Workplace Victimisation

Socio-demographic characteristics that have previously been studied in relation to workplace violence of emergency responders are typically age and gender. Often, men are found to experience more workplace violence than females,44x M. Abraham, A. van Hoek, P. Hulshof & J. Pach, Geweld tegen de politie in uitgaansgebieden [Violence against the Police in Nightlife] (2007); J.T. Grange and S.W. Corbett, ‘Violence against Emergency Medical Services Personnel’, 6 Prehospital Emergency Care 186 (2002); Middelhoven and Driessen, above n. 7; A. Oliver and R. Levine, ‘Workplace Violence: A Survey of Nationally Registered Emergency Medical Services Professionals’, Epidemiology Research International (2015). with the exception of sexual harassment, which is more often experienced by females.45x C. Mayhew and D. Chappell, ‘Occupational Violence: Types, Reporting Patterns and Variations between Health Sectors’, Taskforce on Prevention and Management of Violence in the Health Workplace Working Paper Series no. 139:1 (2001). M. Boyle, S. Koritsas, J. Coles & J. Stanley, ‘A Pilot Study of Workplace Violence Towards Paramedics’, 24 Emergency Medicine Journal 760 (2007). Often, younger professionals are found to be more likely to experience workplace violence.46x Abraham et al. (2007), above n. 44; Grange and Corbett, above n. 44; Middelhoven and Driessen, above n. 7. No association was found between ethnicity and victimisation of professionals.47x Ettema and Bleijendaal, above n. 18. As described, these characteristics are theoretically related to workplace violence by people having specific lifestyles because of their socio-demographic characteristics. However, studies have not shown which lifestyle characteristics are mediating the relationship between being young and male, and experiencing workplace violence. For example, theoretically, young professionals could experience more victimisation, because they have had less experience and training (lacking safety precautions) or because older professionals have less contact with citizens (possibly motivated offenders) because they do more desk work.

According to previous studies, various situational characteristics explain differences in victimisation of emergency responders. To explain differences in workplace violence experiences between emergency responders, the profession itself is an important situational indicator.48x Abraham et al. (2011), above n. 8. The profession determines the situation professionals are in and the type of contact they have with citizens (as described in para. 2). However, other characteristics are important to explain differences in victimisation within professions. Professionals who are more in contact with people are more likely to experience victimisation, as indicated by studies that found working more hours per week and having more contact with citizens to be related to external workplace violence.49x Abraham et al. (2007), above n. 44; J. Broekhuizen, J. Raven & F. Driessen, Geweld tegen de brandweer [Violence against Firefighters] (2005); Gates et al., above n. 3; Koritsas et al., above n. 20; Middelhoven and Driessen, above n. 7; LeBlanc and Kelloway, above n. 24; C. Sikkema, M. Abraham & S. Flight, Ongewenst gedrag besproken [Undesirable Conduct Discussed] (2007); Van Reemst et al., above n. 16. In addition, the type of contact with citizens (including location and time of contact) and the type of citizens they work with are related to experiencing workplace violence. According to studies, professionals experience more workplace violence if they work in economically depressed areas, in urban areas, in public spaces, on their own, during the evening or at night, or, more often, in contact with citizens who are unknown to the professional.50x Id.; Boyle et al., above n. 45; R.J. Kaminski, ‘Assessing the County-Level Structural Covariates of Police Homicides’, 12 Homicide Studies 350 (2008); Oliver and Levine, above n. 44. In addition, professionals who deal with more ‘incidents’ (such as arresting people)51x J. Timmer, Politiegeweld: Geweldgebruik van en tegen de politie [Police Violence: Violence by and against the Police] (2005). or have more ‘bad news conversations’ are more often confronted with workplace violence. Regarding their work location, professionals who work in an urban area are found to experience more workplace victimisation.52x K. Barrick, M.J. Hickman & K.J. Strom, ‘Representative Policing and Violence towards the Police’, 8 Policing 193 (2014); M.G. Jenkins, L.G. Rocke, B.P. McNicholl & D.M. Hughes, ‘Violence and Verbal Abuse against Staff in Accident and Emergency Departments: A Survey of Consultants in the UK and the Republic of Ireland’, 15 Journal of Accident & Emergency Medicine 262 (1998). Also, professionals who work with people who use alcohol or drugs, who have previously been in contact with the police or who have a mental illness are more likely to experience external workplace violence.53x Grange and Corbett, above n. 44; Jenkins et al., above n. 52; L. Loef, M. Heijke & B. Van Dijk, Typologie van plegers van geweldsdelicten [Typology of Perpetrators of Violence] (2010); Naeye and Bleijendaal, above n. 4; J.L. Taylor and L. Rew, ‘A Systematic Review of the Literature: Workplace Violence in the Emergency Department’, 20 Journal of Clinical Nursing 1072 (2010). All these characteristics seem related to how often professionals are in the presence of possible motivated offenders or lack guardianship.

It is possible also that the organisational climate influences the amount of workplace victimisation by their prevention and aftercare policies with respect to aggression and violence, as this is found to be related to workplace violence in other populations.54x S.R. Kessler, P.E. Spector, C. Chang & A.D. Parr, ‘Organizational Violence and Aggression: Development of the Three-Factor Violence Climate Survey’, 22 Work & Stress 108; P.E. Spector, M.L. Coulter, H.G. Stockwell & M.W. Matz, ‘Perceived Violence Climate: A New Construct and its Relationship to Workplace Physical Violence and Verbal Aggression, and their Potential Consequences’, 21 Work & Stress 117 (2007). Prevention and aftercare measures of organisation may affect the nature of interaction between professionals and citizens, for example by training, which may provide a safety precaution against experiencing workplace violence.

As shown, many characteristics have already been found to be related to experiencing workplace violence. However, there is still the need to improve the explanation of differences in victimisation for three reasons. First, because it is rather difficult to directly use these situational and socio-demographic characteristics in interventions, as they are either relatively stable or unwanted to change. For example even though working at night seems to pose more threat, we would not want to stop emergency care at night. I will come back to this issue in the discussion of this paper. Second, because studies show that the differences in experiences of workplace violence that are explained by (only) situational and socio-demographic characteristics is limited.55x Abraham et al. (2011), above n. 8; Fischer and Van Reemst, above n. 18; Naeye and Bleijendaal, above n. 4. Lastly, because criminal opportunity theories mainly focus on being in the same time and place as an offender and not the motivation of offenders. Therefore, studies using these theories rarely, or indirectly, describe victim characteristics that may influence the motivation of the offender, thereby lacking a possibly important element for explaining workplace violence.4.2.1 Professionals’ Vulnerability

The other element of being suitable as a target is the idea of being more ‘attractive’ (although some researchers have highlighted the unwanted connotations of this word),56x D. Finkelhor and N.L. Asdigian, ‘Risk Factors for Youth Victimization: Beyond a Lifestyle/Routine Activities Theory Approach’, 11 Violence and Victims 3 (1996) at 5. as a possible target, which is the core idea of vulnerability notions of victims, originating from the victim precipitation theory. The victim precipitation theory explains that the victim might contribute to the victimisation experience.57x Meier and Miethe (1994), above n. 37; M.E. Wolfgang, Patterns in Criminal Homicide (1958). According to further developments of the theory, this happens by being more ‘vulnerable’ to being victimised than others, in other words more ‘victimisation prone’.58x See e.g. J. Goodey, Victims and Victimology: Research, Policy and Practice (2005), at 70. Originally, precipitation was considered to occur whenever the victim first used physical force against the subsequent offender.59x Wolfgang, above n. 57. Following this idea, several researchers studied the extent to which serious crime followed action from the victim, such as physical force.60x M. Amir, Patterns in Forcible Rape (1971); L.A. Curtis, ‘Victim Precipitation and Violent Crime’, 21 Social Problems 594 (1973); and more recently: S.M. Ganpat, J. van der Leuk & P. Nieuwbeerta, ‘The Influence of Event Characteristics and Actors’ Behaviour on the Outcome of Violent Events: Comparing Lethal with Non-lethal Events’, 53 British Journal of Criminology 685 (2013); L.R. Muftic, L.A. Bouffard & J.A. Bouffard, ‘An Exploratory Analysis of Victim Precipitation among Men and Women Arrested for Intimate Partner Violence’, 2 Feminist Criminology 327 (2007). The theory was debated because it was considered as blaming the victim, which I will elaborate upon later in this paper. However, the idea that some people are more vulnerable to victimisation than others remained.

This idea was further developed among others by Sparks,61x R.F. Sparks, ‘Multiple Victimization: Evidence, Theory and Future Research’, 72 Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology 762 (1981). who developed six characterisations of victim proneness: precipitation (precipitation or encouraging victimisation), facilitation (putting themselves consciously or subconsciously at risk, e.g. by forgetting to protect oneself), vulnerability (attributes which lead to higher victimisation risk), opportunity (people must be in the same place as the offender), attractiveness (e.g. wearing jewellery in case of theft) or impunity (unlikely to report to the police).

There seems to be overlap between these vulnerability notions and criminal opportunity theories, as both highlight the role of opportunity and protection (in other words, guardianship), but vulnerability notions seem to add the role victim may have in the motivation of the offender: They might encourage, facilitate or attract victimisation, besides being in the same time and space as offenders. In this way, the actual interaction between offender and victim receives more attention, than in opportunity theories. Finkelhor and Asdigian highlight that victims may have characteristics that an offender may want to obtain or use (influencing the ‘instrumental goal’ of aggressiveness62x R.B. Felson, ‘Violence as Instrumental Behavior’, in E. Kelloway, J. Barling & J. Hurrell (eds.), Handbook of Workplace Violence (2006) 7. of possible offenders), may arouse anger or jealousy (influencing the ‘frustration-aggression’ of possible offenders), or may compromise the ability to resist or deter victimisation.63x Finkelhor and Asdigian, above n. 56.

Thus, some people may be more vulnerable to experiencing victimisation, for example by having certain psychological characteristics including emotional, cognitive, personality and behavioural characteristics. Probably, psychological characteristics are not directly, but rather indirectly related to victimisation. For example Egan and Perry64x S.K. Egan and D.G. Perry, ‘Does Low Self-Regard Invite Victimization?’, 34 Developmental Psychology 299 (1998). describe that having low self-regard may be associated to experiencing victimisation, because of lower motivation to act assertively or to defend oneself. As can be derived from the notion of Egan and Perry, emotional, cognitive and personality characteristics seem related to victimisation because of the behaviour victims perform.

In general victimisation literature, originally based on victims of bullying, two types of victims are distinguished based on their behaviour and related psychological characteristics: the passive (or submissive) and the provocative victim.65x D. Olweus, Aggression in the Schools: Bullies and Whipping Boys (1978); D. Olweus, ‘Victimization by Peers: Antecedents and Long-Term Outcomes’, in K.H. Rubin and J.B. Asendorpf (eds.), Social Withdrawal, Inhibition, and Shyness in Childhood 315 (1993); D. Olweus, Bullying at School (1994). The passive victim is characterised to be passive, insecure and frequently rejected. The provocative victim is characterised to be aggressive, hostile or irritating. In many general victimisation studies, passive and aggressive behaviour have been found to be related to victimisation.66x J.N. Kingery, C.A. Erdly, K.C. Marshall, K.G. Whitaker & T.R. Reuter, ‘Peer Experiences of Anxious and Socially Withdrawn Youth: An Integrative Review of the Developmental and Clinical Literature’ 13 Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review 91 (2010); C. Salmivalli and T. Helteenvuori, ‘Reactive, but not Proactive Aggression Predicts Victimization among Boys’, 33 Aggressive Behavior 198 (2007).4.2.2 Psychological Characteristics and Behaviour of Professionals

The passive and provocative victims were also proposed in mainly internal, but also external, workplace violence studies.67x K. Aquino and K. Lamertz, ‘A Relational Model of Workplace Victimization: Social Roles and Patterns of Victimization in Dyadic Relationships’, 89 Journal of Applied Psychology 1023 (2004); E. Kim and T.M. Glomb, ‘Get Smarty Pants: Cognitive Ability, Personality and Victimization’, 95 Journal of Applied Psychology 889 (2010) at 890. Studies that address individual characteristics and victimisation at a certain point in time (cross-sectional studies) indicate that victims score higher on aggressive and dominating behaviour and lower on self-determination than non-victims.68x K. Aquino, S.L. Grover, M. Bradfield & D.G. Allen, ‘The Effects of Negative Affectivity, Hierarchical Status and Self-Determination on Workplace Victimization’, 42 Academy of Management Journal 260 (1999); K. Aquino and M. Bradfield, ‘Perceived Victimization in the Workplace: The Role of Situational Factors and Victim Characteristics’, 11 Organization Science 525 (2000); K. Aquino and K. Byron, ‘Dominating Interpersonal Behaviour and Perceived Victimization in Groups: Evidence for a Curvilinear Relationship’, 28 Journal of Management 69 (2002). Whereas having more dominating behaviour supports the notion of the more provocative victim, lower self-determination could support the notion of the more passive victim. This was not yet structurally tested among emergency responders, although interviews performed in these populations point in the same direction.69x W. Roeleveld and I. Bakker, Slachtofferschap van geweld binnen de publieke taak [Victimization of Violence in the Public Task] (2010).

Regarding psychological characteristics, relatively little information was available about indicators of external workplace violence of emergency responders. Studies that have addressed psychological characteristics have mainly focused on police officers. These indicate that police officers who score higher on neuroticism and openness to experience,70x K. Ellrich and D. Baier, ‘The Influence of Personality on Violent Victimization – A Study on Police Officers’, Psychology, Crime & Law (2016). who experience more job-related stress71x E. Zavala, ‘Examining the Offender-Victim Overlap among Police Officers: The Role of Social Learning and Job-Related Stress’, 28 Violence and Victims 731 (2013). and who select aggressive responses72x L. van Reemst, T.F.C. Fischer & B.W.C. Zwirs, ‘Response Decision, Emotions, and Victimization of Police Officers’, 12 European Journal of Criminology 635 (2015). experience more workplace violence. In other populations, more psychological characteristics have been addressed, such as victims having more general negative affectivity,73x A.A. Grandey, D.N. Dickter & H. Sin, ‘The Customer Is Not Always Right: Customer Aggression and Emotion Regulation of Service Employees’, 25 Journal of Organizational Behavior 397 (2004). emotional exhaustion,74x Grandey et al. (2004), above n. 73; Grandey et al. (2007), above n. 10; M.S. Hershcovis and J. Barling, ‘Toward’ a Multi-Foci Approach to Workplace Aggression: A Meta-Analytic Review of Outcomes from Different Perpetrators’, 31 Journal of Organizational Behavior 24 (2010); S. Winstanley and L. Hales, ‘A Preliminary Study of Burnout in Residential Social Workers Experiencing Aggression: Might It Be Cyclical?’, 45 British Journal of Social Work 24 (2014). psychological distress,75x H.J. Gettman and M.J. Gelfand, ‘When the Customer Shouldn’t Be King: Antecedents and Consequences of Sexual Harassment by Clients and Customers’, 92 Journal of Applied Psychology 757 (2007). feelings of unsafety,76x Gates et al., above n. 3. risk perception,77x LeBlanc and Kelloway, above n. 24. mental and physical health,78x Dupre et al., above n. 27; Hershcovis and Barling, above n. 74; Schat and Frone, above n. 27. and lower self-esteem79x Bowling and Beehr, above n. 29. than non-victims. These could be related to workplace victimisation of emergency responders as well.

Again, it is important to note that it is often unclear whether these psychological characteristics preceded or were a result from experiencing workplace violence. More research is needed that studies psychological characteristics and workplace violence over time, to determine whether these are indicators or consequences of experiencing workplace violence. Especially for feelings of unsafety and physical health, it seems likely that these are consequences of experiencing workplace violence rather than indicators, whereas for stable personality characteristics, such as neuroticism and openness to experience, it seems likely that these characteristics existed before experiencing workplace violence. For other characteristics, the direction of the relationship is less obvious. For example one could experience more negative feelings as a result of victimisation. In the other direction, by having negative feelings, professionals could approach a situation more ‘negatively’, which could result in being less able to de-escalate a potentially threatening situation (because they did not perceive the threat on time, for example) or allowing a situation to escalate sooner (e.g. by being less friendly). Therefore, research is needed that studies the relationships over time.

In addition, more knowledge is needed about the relationship between psychological characteristics and workplace violence for emergency responders specifically, as many studies focus on other populations. For example as dominance, aggression and lower self-esteem have been linked to victimisation (including violence in the workplace) in other populations, this should also be studied in police officers, firefighters and emergency medical workers. Studying dominance could especially be interesting for police officers, as a certain degree of dominance seems relevant to accurately perform as a police officer, because of the work tasks of the police.

In addition, more characteristics could influence the degree of (de-)escalation of the situation and thus the extent of workplace violence the professional experiences. For example, in various contexts, people seem to adjust their behaviour according to how they interpret situations.80x N.R. Crick and K.A. Dodge, ‘A Review and Reformulation of Social Information-Processing Mechanisms in Children’s social Adjustment’, 1 Psychological Bulletin 74 (1994). K.A. Dodge, ‘A Social Information Processing Model of Social Competence in Children’, in M. Perlmutter (ed.), Minnesota Symposium on Child Psychology (1986) 77. Studies in other populations also found these interpretations, referred to as hostile attributions of the situation, to be related to victimisation: people who interpret hypothetical situations as more hostile, generally, also experience more victimisation.81x L. van Reemst, T.F.C. Fischer & B.W.C. Zwirs, ‘Social Information Processing Mechanisms and Victimization: A Literature Review’, 17 Trauma, Violence, and Abuse 3 (2016). Aquino, Douglas and Martinko82x K. Aquino, S. Douglas & M.J. Martinko, ‘Overt Anger in Response to Victimization: Attributional Style and Organizational Norms as Moderators’, 9 Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 152 (2004). have found a relationship between workplace violence and various other negative attributions, namely the tendency to attribute negative outcomes as external to themselves, stable, intentional and controllable. Studying hostile attributions as a possible indicator of workplace violence could thus be worthwhile. -

5 Blaming the Victim by Considering Professionals’ Suitability

A risk in studying victim characteristics in workplace violence, such as their psychological or behavioural characteristics, is that it might be considered blaming the victim. This is one of the ethical dilemmas researchers have to deal with when studying this topic. In particular, the victim precipitation theory and related vulnerability notions are often considered to hold the victim to a greater or smaller extent responsible for experiencing victimisation.

The explanation that is commonly given for blaming the victim to occur is that people tend to believe in a just world.83x S. Hamby and J. Grych, ‘The Complex Dynamics of Victimization: Understanding Differential Vulnerability without Blaming the Victim’, in C.A. Cuevas and C.M. Rennison (eds.), The Wiley Handbook on the Psychology of Violence (2016). M. Stel, K. van den Bos & M. Bal, ‘On Mimicry and the Psychology of the Belief in a Just World: Imitating the Behaviors of other Reduces the Blaming of Innocent Victims’, 25 Social Justice Research 14 (2012). According to the just world theory,84x M.J. Lerner, The Belief in a Just World (1980). people have a basic need to believe that the world is just, that good things happen to good people and bad things happen to bad people. This protects them from the idea that something bad could happen to them. As a response, they may believe that the victim has done something to deserve what happened to them, and therefore blame the victim. In addition, Hamby and Grych85x Hamby and Grych, above n. 83. describe the high premium on risk reduction in American culture, and probably also in other Western cultures. This comes with the idea that people have a responsibility to protect themselves: they should take (sometimes extreme) steps to stop or avoid their vulnerability to violence.5.1 Victim Blaming in Theories and Empirical Studies about Workplace Violence

In the context of victimological theories and in particular the victim precipitation theory, the study of victims originated from the culture of the criminal law, focusing on degrees of innocence or blame for events.86x Goodey, above n. 58; H. von Hentig, The Criminal & His Victim (1948); B. Mendelsohn, ‘A New Branch of Bio-Psychological Science: La Victimology’, 10 Revue Internationale de Criminologi et de police technique 782 (1956). In addition, as described, the original study of victim precipitation focused on physical force performed by the victim, previous to the crime.87x Wolfgang, above n. 57. Focusing on the innocence or blame, this theory was soon considered to blame the victim. Although there are explanations for why people blame victims, blaming the victim does not seem considered politically correct or socially acceptable, which is reflected in the legal system that tries to find and prosecute offenders and tries to compensate victims. This resulted in the fear of blaming the victim and tendency to avoid blaming the victim.88x O. Zur, ‘Rethinking “Don’t Blame the Victim”: The Psychology of Victimhood’, 4 Journal of Couple Therapy 15 (1995).

The fear of blaming the victim may cause the concern among researchers and professionals that addressing potential victim characteristics in research will be considered victim blaming and will promote further victim blaming.89x Hamby and Grych, above n. 83. No other victimological theory than the victim precipitation theory has looked so explicitly to the role of victims in victimisation. Therefore, this theory has probably received the most criticism and has been considered as blaming the victim.

Regarding empirical studies, this fear of blaming the victim might result in less cooperation in studies, and less acceptance of results of studies about victim characteristics or interventions about preventing workplace violence, thereby lowering the effectiveness of studies and interventions. Possibly as a response to the discussion on blaming the victim, research often does not explicitly refer to the victim precipitation theory, even though describing the vulnerability of the victim.90x Finkelhor and Asdigian, above n. 56; Tillyer et al., above n. 43. Victim blaming could even be a reason not to study or communicate about (specific) victim characteristics, although it is difficult to determine to what extent this has occurred.

However, the theory and empirical studies do not explicitly attribute blame or state that the victim deliberately provoked victimisation. As Hambly and Grych state: ‘Attribution of blame hinges on the intentionality of an action’.91x Hamby and Grych, above n. 83. Victims, and in this case professionals, may not have freely chosen the behaviour or psychological characteristics that might influence experiencing violence, and did not intend it to result in the victimisation.92x K.G. Shaver, The Attribution of Blame, Causality, Responsibility, and Blameworthiness (1985). Vulnerability notions and studies do provide important information: they suggest that victims may have vulnerable characteristics, and it also suggests that victimisation is an outcome that is influenced by offender-victim interaction. Victim characteristics may thus indirectly or unknowingly influence victimisation. And this is also addressed by other victimological theories such as the criminal opportunity theories, which address congruence of a suitable target, lacking guardianship and a motivated offender.

More recently, researchers in workplace violence seem to increasingly study victim characteristics in external workplace violence, but always seem aware of the possibility that it may be perceived as blaming the victim, by addressing some sentences to this discussion.93x See e.g. Muftic et al., above n. 60. Studying victim characteristics is important to find out which characteristics protect people from being victimised, even though being in risky situations at times. If we do not study what characteristics pose more risk, we will not know which characteristics pose less risk for victimisation. Therefore, by increasingly allowing victim characteristics to be studied, we gain more knowledge on how to prevent victimisation, for example by using this knowledge in training for professionals. -

6 Discussion

In this paper, I have provided a theoretical framework for studying differences in external workplace violence. I proposed that researchers should take into account both situational and victim characteristics to gain a broader perspective on experiencing workplace violence. Situational characteristics could be characteristics of the work task, the work situation (including the type of people they deal with) or the organisation of professionals. In addition, research should take into account victim characteristics, which are briefly mentioned by criminal opportunity theories but are elaborated upon in the (further developments of the) victim precipitation theory. Whereas criminal opportunity theories focus on the presence of motivated offenders, being suitable and lacking guardianship in time and place (and socio-demographic that are indicators of this presence), the victim precipitation theory focuses, primarily, on being vulnerable because of psychological or behavioural characteristics.

The reviewed knowledge and gaps in the literature provide important directions for future research and practice. First, many studies that were described focus on either situational characteristics or victim characteristics. We would gain more knowledge about workplace violence and how to prevent it, if we take both perspectives into account. In addition to studying both types of characteristics, researchers should examine the interaction between individuals and situations, as, in general, the relationship between person and situation seems to be reciprocal and interdependent.94x P. Wilcox, C.J. Sullivan, S. Jones & J.-L. Van Gelder, ‘Personality and Opportunity: An Integrated Approach to Offending and Victimization’, 41 Criminal Justice and Behavior 880 (2014); R. Wortley, ‘Exploring the Person-Situation Interaction in Situational Crime Prevention’, in N. Tilley and G. Farrell (eds.), The Reasoning Criminologist: Essays in Honour of Ronald V. Clarke (2012) 184. Police officers, fire fighters and emergency medical workers may each have unique personal characteristics because of self-selection (particular kinds of persons may be chosen for these jobs), selection processes at the organisation, training received or experiences at work. Therefore, the profession or the specific work conditions (situational characteristics) should be analysed in interaction with victim characteristics, to examine which characteristics may, independently of other characteristics, prevent violence in which situations or jobs. For example the possible differences between the three types of emergency responders should be addressed. The unique characteristics and work situations of these types of professionals may allow differences in relationships between characteristics and workplace violence, which have, to my knowledge, not been tested among emergency responders yet.

Second, although an increasing number of studies focus on victim characteristics, few have addressed victim characteristics in studies about emergency responders. It would be interesting to study which characteristics are indicators of external workplace violence experienced by emergency responders, and by which emergency responders. Therefore, future studies will need to test to what extent the known correlates of workplace violence in other populations, such as dominance, aggression and self-esteem, are indicators of workplace victimisation of emergency responders as well.

Third, as described, the design of most studies about workplace violence is cross-sectional, measuring characteristics and workplace violence at a certain point in time. Future studies should provide more information about how characteristics are related, for example if victim characteristics were present before victimisation or were developed after victimisation. As an experimental study is unethical in case of experiencing victimisation, one way of addressing the direction of relationships would be research using a longitudinal design, such as a cross-lagged panel design.95x D.A. Kenny ‘Cross-Lagged Panel Correlation: A Test for Spuriousness’, 82 Psychological Bulletin 887 (1975). Victim characteristics and experienced external workplace violence would be measured during multiple time points (e.g. six or twelve months apart), and the relationship between characteristics and experienced victimisation would be analysed while taking into account characteristics and victimisation at the other point in time. In this way, we gain knowledge about the direction of relationships.

Lastly, regarding implications of addressed characteristics for the prevention of workplace violence, the criminal opportunity theories propose adjustments to the context of the workplace, and the victim precipitation theory proposes adjustments to the professional. It is important to bear our other goals in mind when considering these adjustments, especially in the context of emergency care. Besides preventing workplace violence, we also want society and people to be safe. Even though preventing workplace violence can have positive effects on professionals, organisations and the quality of work, it could have negative side effects. For example if emergency responders do not have any contact with citizens or do not work at night, they will most likely not be victimised by citizens, as these were found to be strong correlates of workplace violence based on the criminal opportunity theories. However, in this way, safeguarding citizens is difficult, or even impossible. Characteristics based on the victim precipitation theory could be addressed by training or selection. For example whereas dominant behaviour was suggested to increase the likelihood of experiencing violence, this behaviour could also be necessary for certain work tasks, such as arresting citizens (for police officers). If so, lowering dominant behaviour by training may not always be wanted. We would thus have to think about these possible side effects and consider developing alternative interventions if we believe unwanted side effects will occur. Possible alternatives are working in larger groups of professionals or having police officers present at night. However, these alternatives do not directly address the correlates and therefore it is needed to first evaluate these types of interventions with regard to their effectiveness. Studying characteristics of the situation and victim provide insight into what type of interventions could be affective.

In addition to possible characteristics related to workplace violence against emergency responders, I addressed how studying characteristics of targets of workplace violence are sometimes interpreted as blaming the victim, which could have negative side effects such as less research and knowledge about workplace violence and how to prevent it. While in particular the victim precipitation theory is often considered to blame the victim, others have argued that professionals may not have freely chosen the behaviour or characteristics that might be ‘attractive’ nor intended it to result in victimisation. For emergency responders, the fear of blaming the victim may be even more present, as emergency responders are important for the safety of society. Being (perceived as) heroes of society and being sent to the front line, any possible disrespect such as ‘trying to blame the professional’ may be disapproved of even more than in other populations. In addition, tension between acting with the risk of inviting violence and spectating with the risk of not avoiding violence is maybe even more difficult for professionals responsible for safety. Therefore, professionals invested in reducing workplace violence against emergency responders should be even more aware of the possibility of being perceived as blaming the victim. Careful and respectful communication about the topic could be a solution.

Overall, this paper contributed to theory development about workplace violence against emergency responders and providing an explanation why addressing characteristics related to differences in workplace violence needed more research. More knowledge about possible risk factors is needed, specifically by longitudinal research addressing a combination of victim and situational characteristics, while looking at differences between police officers, fire fighters and emergency medical workers. In this way, knowledge on workplace violence will be gained and effective prevention strategies can be developed. -

1 D.S. Weiss, A. Brunet, S.R. Best, T.J. Metzler, A. Liberman, N. Pole, J.A. Fagan & C.R. Marmar, ‘Frequency and Severity Approaches to Indexing Exposure to Trauma: The Critical Incident History Questionnaire for Police Officers’, 23 Journal of Traumatic Stress 734 (2010).

-

2 See ‘Violence at Work’, available at: <www.hse.gov.uk/Statistics/causinj/violence/index.htm> (last visited 23 March 2016).

-

3 D.M. Gates, C.S. Ross & L. McQueen, ‘Violence against Emergency Department Workers’, 31 The Journal of Emergency Medicine 331 (2006); C.E. Rabe-Hemp and A.M. Schuck, ‘Violence against Police Officers’, 10 Police Quarterly 411 (2007).

-

4 J. Naeye and R. Bleijendaal, Agressie en geweld tegen politiemensen [Aggression and violence directed at police] (2008).

-

5 T.M. Leino, R. Selin, H. Summala & M. Virtanen, ‘Violence and Psychological Distress among Police Officers and Security Guards’, 61 Occupational Medicine 400 (2011).

-

6 M. Bernaldo-De-Quiros, A.T. Piccini, M.M. Gomez & J.C. Cerdeira, ‘Psychological Consequences of Aggression in Pre-hospital Emergency Care: Cross Sectional Survey’, 52 International Journal of Nursing Studies 260 (2015).

-

7 L. Middelhoven and F. Driessen, Geweld tegen werknemers in de openbare ruimte [Violence against Employees in the (Semi-)Public Space] (2001).

-

8 M. Abraham, S. Flight & W. Roorda, Agressie en geweld tegen werknemers met een publieke taak [Aggression and Violence against Employees with a Public Task] (2011), at 36.

-

9 See ‘About Law Enforcement Officers Killed and Assaulted, 2013’, available at: <www.fbi.gov/about-us/cjis/ucr/leoka/2013> (last visited 22 September 2015).

-

10 A.A. Grandey, J.H. Hern & M.R. Frone, ‘Verbal Abuse from Outsiders versus Insiders: Comparing Frequency, Impact on Emotional Exhaustion, and the Role of Emotional Labor’, 12 Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 63 (2007); M.T. Sliter, S.Y. Pui, K.A. Sliter & S.M. Jex, ‘The Differential Effects of Interpersonal Conflict from Customers and Coworkers: Trait Anger as a Moderator’, 16 Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 424 (2011).

-

11 Id.

-

12 Eurofound, Physical and Psychological Violence at the Workplace (2013).

-

13 Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations, Handreiking agressie en geweld [Guide to Aggression and Violence] (2011).

-

14 See ‘Geweld tegen werknemers met publieke taak’, available at: <www.rijksoverheid.nl/onderwerpen/geweld-tegen-werknemers-met-publieke-taak/inhoud/aanpak-geweld-tegen-werknemers-met-publieke-taak> (last visited 22 September 2015).

-

15 See e.g. K.H. Breitenbecher, ‘Sexual Revictimization among Women. A Review of the Literature Focusing on Empirical Investigations’, 6 Aggression and Violent Behavior 415 (2001); G. Farrell and A.C. Bouloukos, ‘International Overview: A Cross-National Comparison of Rates of Repeat Victimization’, 12 Crime Prevention Studies 5 (2001).

-

16 L. van Reemst, T.F.C. Fischer & B.W.C. Zwirs, Geweld tegen de politie: De rol van mentale processen van de politieambtenaar [Violence against the Police: The Role of Mental Processes of the Police Officer] (2013).

-

17 It is important to note that victimisation, as measured in self-report victimisation surveys, is probably a combination of the actual frequency of victimisation and how likely it is that people report this victimisation in a survey (e.g. based on to what extent they remember the incidence or experienced harm from the victimisation incidence). This is often considered a limitation of victimisation surveys, as it does not allow the separation of actual and perceived victimisation. However, if we are interested in decreasing experiences of victimisation, this combination of frequency and remembrance or harm of victimisation could be considered our concept of interest in victimisation studies.

-

18 Abraham et al. (2011), above n. 8; A. Ettema and R. Bleijendaal, Slachtofferprofielen [Victim Profiles] (2010); T.F.C. Fischer and L. Van Reemst, Slachtofferschap in de publieke taak [Victimisation in the Public Task] (2014).

-

19 Fischer and Van Reemst, above n. 18.

-

20 See e.g. C.C. Mechem, E.T. Dickinson, F.S. Shofer & D. Jaslow, ‘Injuries from Assaults on Paramedics and Firefighters in an Urban Emergency Medical Services System’, 6 Prehospital Emergency Care 396 (2002); S. Koritsas, M. Boyle & J. Coles, ‘Factors Associated with Workplace Violence in Paramedics’, 24 Prehospital and Disaster Management 417 (2009).

-

21 Some examples in other populations: T.F.C. Fischer, L. van Reemst & J. de Jong, ‘Workplace Aggression Toward Local Government Employees: Target Characteristics’, International Journal of Public Sector Management (2016); S. Landau and Y. Bendalak, ‘Personnel Exposure to Violence in Hospital Emergency Wards: A Routine Activity Approach’, 34 Aggressive Behavior 88 (2008); F. van Mierlo and S. Bogaerts, ‘Vulnerability Factors in the Explanation of Workplace Aggression’, 11 The Journal of Forensic Psychology Practice 265 (2011).

-

22 J. van Dijk, ‘Free the Victim: A Critique of the Western Conception of Victimhood’, 16 International Review of Victimology 1 (2009).

-

23 See also S.N. Kales, A.J. Tsismenakis, C. Zhang & E.S. Soteriades, ‘Blood Pressure in Firefighters, Police Officers, and Other Emergency Responders’, 22 American Journal of Hypertension 11 (2009).

-

24 See e.g. M.M. LeBlanc and E.K. Kelloway, ‘Predictors and Outcomes of Workplace Violence and Aggression’, 87 Journal of Applied Psychology 444 (2002).

-

25 See e.g. G.P. Alpert, R.G. Dunham & J.M. MacDonald, ‘Interactive Police-Citizen Encounters that Result in Force’, 7 Police Quarterly 475 (2004).

-

26 Similar to other occupations. For example studies in the general health care sector have indicated that different occupations may result in differences in EWPV and correlates of EWPV. E. Viitasara, M. Sverke & E. Menckel, ‘Multiple Risk Factors for Violence to Seven Occupational Groups in the Swedish Caring Sector’, 58 Industrial Relations 202 (2003); S. Winstanley and R. Whittington, ‘Violence in a General Hospital: Comparison of Assailant and Other Assault-Related Factors on Accident and Emergency and Inpatient Wards’, 106 Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 144 (2002).

-

27 A.C.H. Schat and M.R. Frone, ‘Exposure to Psychological Aggression at Work and Job Performance: The Mediating Role of Job Attitudes and Personal Health’, 25 Work & Stress 23 (2011); K.E. Dupre, K.A. Dawe & J. Barling, ‘Harm to Those Who Serve: Effects of Direct and Vicarious Customer-Initiated Workplace Aggression’, 29 Journal of Interpersonal Violence 1 (2014).

-

28 J. Barling, K.E. Dupre & E.K. Kelloway, ‘Predicting Workplace Aggression and Violence’, 60 Annual Review of Psychology 671 (2009).

-

29 K. Aquino and S. Thau, ‘Workplace Victimization: Aggression from the Target’s Perspective’, 60 Annual Review of Psychology 717 (2009); N.A. Bowling and T.A. Beehr, ‘Workplace Harassment from the Victim’s Perspective: A Theoretical Model and Meta-Analysis’, 91 Journal of Applied Psychology 998 (2006); B.J. Tepper, ‘Abusive Supervision in Work Organizations: Review, Synthesis and Research Agenda’, 33 Journal of Management 261 (2007).

-

30 B.L. Bigham, J.L. Jensen, W. Tavares, I.R. Drennan, H. Saleem, K.N. Dainty & G. Munro, ‘Paramedic Self-Reported Exposure to Violence in the Emergency Medical Services (EMS) Workplace: A Mixed-Methods Cross-Sectional Survey’, 18 Prehospital Emergency Care 489 (2014).

-

31 C. Mayhew and D. Chappell, ‘Workplace Violence: An Overview of Patterns of Risk and the Emotional/Stress Consequences on Targets’, 30 International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 327 (2007); D. Yagil, ‘When the Customer Is Wrong: A Review of Research on Aggression and Sexual Harassment in Service Encounters’, 13 Aggression and Violent Behavior 141 (2008).

-

32 See e.g. M.M. LeBlanc, K. Dupre & J. Barling, ‘Public-Initiated Violence’, in E. Kelloway, J. Barling & J. Hurrell (eds.), Handbook of Workplace Violence (2006) 261.

-

33 Abraham et al. (2011), above n. 8, at 29.

-

34 See e.g. Bigham et al., above n. 30.

-

35 M.J. Hindelang, M.R. Gottfredson & J. Garofalo, Victims of Personal Crime: An Empirical Foundation for a Theory of Personal Victimization (1978).

-

36 L.E. Cohen and M. Felson, ‘Social Change and Crime Rate Trends: A Routine Activity Approach’, 44 American Sociological Review 588 (1979).

-

37 R.F. Meier and T.D. Miethe, ‘Understanding Theories of Criminal Victimization’, 17 Crime and Justice 459 (1993); R.F. Meier and T.D. Miethe, Crime and Its Social Context: Towards an Integrated Theory of Offenders, Victims, and Situations (1994).

-

38 L.E. Cohen, J.R. Kluegel & K.C. Land, ‘Social Inequality and Predatory Criminal Victimization: An Exposition and Test of a Formal Theory’, 46 American Sociological Review 505 (1981).

-

39 Hindelang et al., above n. 35.

-

40 Cohen and Felson, above n. 36.

-

41 Meier and Miethe (1993), above n. 37, at 470.

-

42 Cohen et al., above n. 38.

-

43 See e.g. K. Holtfreter, M.D. Reisig & T.C. Pratt, ‘Low Self-Control, Routine Activities, and Fraud Victimization’, 46 Criminology 189 (2008); Landau and Bendalak, above n. 21; T.J. Taylor, A. Freng, F.A. Esbensen & D. Peterson, ‘Youth Gang Membership and Serious Violent Victimization: The Importance of Lifestyles and Routine Activities’, 23 Journal of Interpersonal Violence 1441 (2008); M.S. Tillyer, R. Tillyer, H.V. Miller & R. Pangrac, ‘Reexamining the Correlates of Adolescent Violent Victimization: The Importance of Exposure Guardianship and Target Characteristics’, 26 Journal of Interpersonal Violence 2908 (2011).

-

44 M. Abraham, A. van Hoek, P. Hulshof & J. Pach, Geweld tegen de politie in uitgaansgebieden [Violence against the Police in Nightlife] (2007); J.T. Grange and S.W. Corbett, ‘Violence against Emergency Medical Services Personnel’, 6 Prehospital Emergency Care 186 (2002); Middelhoven and Driessen, above n. 7; A. Oliver and R. Levine, ‘Workplace Violence: A Survey of Nationally Registered Emergency Medical Services Professionals’, Epidemiology Research International (2015).

-

45 C. Mayhew and D. Chappell, ‘Occupational Violence: Types, Reporting Patterns and Variations between Health Sectors’, Taskforce on Prevention and Management of Violence in the Health Workplace Working Paper Series no. 139:1 (2001). M. Boyle, S. Koritsas, J. Coles & J. Stanley, ‘A Pilot Study of Workplace Violence Towards Paramedics’, 24 Emergency Medicine Journal 760 (2007).

-

46 Abraham et al. (2007), above n. 44; Grange and Corbett, above n. 44; Middelhoven and Driessen, above n. 7.

-

47 Ettema and Bleijendaal, above n. 18.

-

48 Abraham et al. (2011), above n. 8.

-

49 Abraham et al. (2007), above n. 44; J. Broekhuizen, J. Raven & F. Driessen, Geweld tegen de brandweer [Violence against Firefighters] (2005); Gates et al., above n. 3; Koritsas et al., above n. 20; Middelhoven and Driessen, above n. 7; LeBlanc and Kelloway, above n. 24; C. Sikkema, M. Abraham & S. Flight, Ongewenst gedrag besproken [Undesirable Conduct Discussed] (2007); Van Reemst et al., above n. 16.

-

50 Id.; Boyle et al., above n. 45; R.J. Kaminski, ‘Assessing the County-Level Structural Covariates of Police Homicides’, 12 Homicide Studies 350 (2008); Oliver and Levine, above n. 44.

-

51 J. Timmer, Politiegeweld: Geweldgebruik van en tegen de politie [Police Violence: Violence by and against the Police] (2005).

-

52 K. Barrick, M.J. Hickman & K.J. Strom, ‘Representative Policing and Violence towards the Police’, 8 Policing 193 (2014); M.G. Jenkins, L.G. Rocke, B.P. McNicholl & D.M. Hughes, ‘Violence and Verbal Abuse against Staff in Accident and Emergency Departments: A Survey of Consultants in the UK and the Republic of Ireland’, 15 Journal of Accident & Emergency Medicine 262 (1998).

-

53 Grange and Corbett, above n. 44; Jenkins et al., above n. 52; L. Loef, M. Heijke & B. Van Dijk, Typologie van plegers van geweldsdelicten [Typology of Perpetrators of Violence] (2010); Naeye and Bleijendaal, above n. 4; J.L. Taylor and L. Rew, ‘A Systematic Review of the Literature: Workplace Violence in the Emergency Department’, 20 Journal of Clinical Nursing 1072 (2010).

-

54 S.R. Kessler, P.E. Spector, C. Chang & A.D. Parr, ‘Organizational Violence and Aggression: Development of the Three-Factor Violence Climate Survey’, 22 Work & Stress 108; P.E. Spector, M.L. Coulter, H.G. Stockwell & M.W. Matz, ‘Perceived Violence Climate: A New Construct and its Relationship to Workplace Physical Violence and Verbal Aggression, and their Potential Consequences’, 21 Work & Stress 117 (2007).

-

55 Abraham et al. (2011), above n. 8; Fischer and Van Reemst, above n. 18; Naeye and Bleijendaal, above n. 4.

-

56 D. Finkelhor and N.L. Asdigian, ‘Risk Factors for Youth Victimization: Beyond a Lifestyle/Routine Activities Theory Approach’, 11 Violence and Victims 3 (1996) at 5.

-

57 Meier and Miethe (1994), above n. 37; M.E. Wolfgang, Patterns in Criminal Homicide (1958).

-

58 See e.g. J. Goodey, Victims and Victimology: Research, Policy and Practice (2005), at 70.

-

59 Wolfgang, above n. 57.

-

60 M. Amir, Patterns in Forcible Rape (1971); L.A. Curtis, ‘Victim Precipitation and Violent Crime’, 21 Social Problems 594 (1973); and more recently: S.M. Ganpat, J. van der Leuk & P. Nieuwbeerta, ‘The Influence of Event Characteristics and Actors’ Behaviour on the Outcome of Violent Events: Comparing Lethal with Non-lethal Events’, 53 British Journal of Criminology 685 (2013); L.R. Muftic, L.A. Bouffard & J.A. Bouffard, ‘An Exploratory Analysis of Victim Precipitation among Men and Women Arrested for Intimate Partner Violence’, 2 Feminist Criminology 327 (2007).

-

61 R.F. Sparks, ‘Multiple Victimization: Evidence, Theory and Future Research’, 72 Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology 762 (1981).

-

62 R.B. Felson, ‘Violence as Instrumental Behavior’, in E. Kelloway, J. Barling & J. Hurrell (eds.), Handbook of Workplace Violence (2006) 7.

-

63 Finkelhor and Asdigian, above n. 56.

-

64 S.K. Egan and D.G. Perry, ‘Does Low Self-Regard Invite Victimization?’, 34 Developmental Psychology 299 (1998).

-

65 D. Olweus, Aggression in the Schools: Bullies and Whipping Boys (1978); D. Olweus, ‘Victimization by Peers: Antecedents and Long-Term Outcomes’, in K.H. Rubin and J.B. Asendorpf (eds.), Social Withdrawal, Inhibition, and Shyness in Childhood 315 (1993); D. Olweus, Bullying at School (1994).

-

66 J.N. Kingery, C.A. Erdly, K.C. Marshall, K.G. Whitaker & T.R. Reuter, ‘Peer Experiences of Anxious and Socially Withdrawn Youth: An Integrative Review of the Developmental and Clinical Literature’ 13 Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review 91 (2010); C. Salmivalli and T. Helteenvuori, ‘Reactive, but not Proactive Aggression Predicts Victimization among Boys’, 33 Aggressive Behavior 198 (2007).

-

67 K. Aquino and K. Lamertz, ‘A Relational Model of Workplace Victimization: Social Roles and Patterns of Victimization in Dyadic Relationships’, 89 Journal of Applied Psychology 1023 (2004); E. Kim and T.M. Glomb, ‘Get Smarty Pants: Cognitive Ability, Personality and Victimization’, 95 Journal of Applied Psychology 889 (2010) at 890.

-

68 K. Aquino, S.L. Grover, M. Bradfield & D.G. Allen, ‘The Effects of Negative Affectivity, Hierarchical Status and Self-Determination on Workplace Victimization’, 42 Academy of Management Journal 260 (1999); K. Aquino and M. Bradfield, ‘Perceived Victimization in the Workplace: The Role of Situational Factors and Victim Characteristics’, 11 Organization Science 525 (2000); K. Aquino and K. Byron, ‘Dominating Interpersonal Behaviour and Perceived Victimization in Groups: Evidence for a Curvilinear Relationship’, 28 Journal of Management 69 (2002).

-

69 W. Roeleveld and I. Bakker, Slachtofferschap van geweld binnen de publieke taak [Victimization of Violence in the Public Task] (2010).

-

70 K. Ellrich and D. Baier, ‘The Influence of Personality on Violent Victimization – A Study on Police Officers’, Psychology, Crime & Law (2016).

-

71 E. Zavala, ‘Examining the Offender-Victim Overlap among Police Officers: The Role of Social Learning and Job-Related Stress’, 28 Violence and Victims 731 (2013).

-

72 L. van Reemst, T.F.C. Fischer & B.W.C. Zwirs, ‘Response Decision, Emotions, and Victimization of Police Officers’, 12 European Journal of Criminology 635 (2015).

-