-

1 Problem Definition and Background

France, Germany, Belgium, and the Netherlands have taken concrete steps to design and develop international commercial courts. Most of the projects claim to be building courts that match the preferences of court users (hereafter the new courts).1xFrom the website of the Netherlands Commercial Court: ‘[…] to create a baseline that judges, lawyers and parties can easily refer to’ (See the website of the NNC: https://www.rechtspraak.nl/English/NCC (last visited 8 February 2019), or the International Chamber of the Paris Court of Appeal […] il est unanimement estimé que pour se rapprocher des standards internationaux, il serait indispensable que nos juridictions répondent, mieux qu’elles ne le font actuellement, aux impératifs de délais exigés pour la resolution des affaires aux enjeux financiers importants.’ (Haut comité juridique de la place financière de Paris, ‘Preconisations sur la mise en place à Paris de chambres specialisees pour le traitement du contentieux international des affaires’, (2017), HCJP, Paris). They also try to challenge England and Wales, which evidence suggests is the most attractive jurisdiction in the EU.2xS. Vogenauer, ‘Regulatory Competition Through Choice of Contract Law and Choice of Forum in Europe: Theory and Evidence’, European Review of Private Law 13, at 53-60 (2013); E. Lein, R. McCorquodale, L. McNamara, H. Kupelyants & J. del Rio, ‘Factors Influencing International Litigants’ Decisions to Bring Commercial Claims to the London Based Courts’ (2015), Ministry of Justice, London. For the success of these projects, it is important that their proposed offer not only correspond with the expectations prospective users, but also manage to attract some of the litigants that go to London. This article argues that lawyers are the most important group of choice makers and that their preferences are not sufficiently matched by the new courts. Lawyers have certain litigation service and court perception preferences. And while the new courts are an improvement compared with the existing courts, they do not sufficiently address lawyers’ preferences, in particular those related to court perception.

This article proceeds as follows. The first section identifies the dominant position lawyers have in relation to their clients and reports findings from a survey I organised on lawyers’ choice-of-court preferences. The second section provides an overview of not only the new courts in the EU, but also the general characteristics of the jurisdiction where they operate. The third section compares the offer of the new courts – within the framework of their jurisdiction – with the demand of their potential court users. It highlights the discrepancy between the preferences of lawyers and the offer of courts. The fourth section concludes this article and offers some recommendations for improvement to court designers and policy makers. -

2 Lawyers’ Choice-of-Court Preferences

This section shows why lawyers dominate their clients and what their most preferred element in making a choice of court is in relation to international commercial cases. The first part of this section identifies lawyers, and not their clients, as the real force when it comes to making a choice of court. The second part reports some of the findings from a survey I organised on lawyers’ choice-of-court preferences in Europe.3xThis survey was conducted during my PhD studies. Results of this study were published in: E. Themeli, Civil Justice System Competition in the European Union (2018), at 266-304.

2.1 Lawyers as Choice-of-Court Makers

Cross-border litigation requires mobility. This means that parties should have financial resources for, knowledge of and, the legal possibility for litigating abroad;4xIn the European Union, parties can make a choice of court agreement, which are regulated by Art. 25 of the Brussels I (recast) Regulation (Regulation (EU) No. 1215/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 December 2012 on jurisdiction and the recognition and enforcement of judgments in civil and commercial matters OJ L 351, 12 December 2012, page 1-32). According to it, parties have considerable freedom to choose any of the courts in the EU despite their domicile or connecting factors with the chosen jurisdiction. Despite some restrictions – for example, the exclusive jurisdiction conferred to some courts by Art. 24 – Art. 25 gives European courts a global reach; it allows even parties with no connection to the EU to litigate in the courts of its Member States. In matters relating to insurance, consumer contracts, and individual contracts of employment choice of court agreement is regulated by Arts. 15, 19, and 23, respectively. These articles aim at providing vulnerable parties an opportunity to reach a choice of court agreement, while offering protection against the abuses of stronger parties. In this view Art. 25 is the most important for the new international commercial courts. For more on Art. 25 see: U. Magnus, ‘Introduction to Articles 25-26’, in U. Magnus and P. Mankowski (eds.), European Commentaries on Private International Law: Brussels Ibis Regulation (2016) 583, at 583-669; F. Garcimartin, ‘Choice-of-Court Agreements’, in A. Dickinson and E. Lein (eds.), The Brussels I Regulation Recast (2015) 277, at 277-306. in addition, they need to overcome certain psychological hurdles. So while there is a broad autonomy to choose a court in the EU5xX.E. Kramer, E. Themeli, ‘The Party Autonomy Paradigm: European and Global Developments on Choice of Forum’, in V. Lazić and S. Stuij (eds.), The Brussels Ibis Regulation: Changes and Challenges of the Renewed Procedural Scheme (2017) 27, at 38-40. and financial difficulties to litigate abroad can be solved, lack of legal knowledge and psychological hurdles are difficult to overcome. Psychological hurdles include diffidence of foreign jurisdictions, choice habits, choice overload, and lack of information.6xChoice habits are important because once established, it is hard to change them. Certain game theories explain that if for some reason a choice option attracts the more attention, that is, is the most chosen, most players develop their strategies assuming that all the others will choose that option. At that point the expectation becomes self-fulfilling, and the option that has a starting edge draws even more attention towards itself. See also: T. Ginsburg, R.H. McAdams, ‘Adjudicating in Anarchy: An Expressive Theory of International Dispute Resolution’, 45 William and Mary Law Review 1229, at 1264-1266, and 1256 (2004). Some choice habits take the form of default contractual terms, and at that point become ‘sticky’. See for more: D. Snyder, ‘Private Lawmaking’, 64 Ohio State Law Journal 371, at 417 (2003). , 7xChoice overload affects lawyers as well. However, when it comes to making a legal choice, lawyers’ choice overload limit may be higher than that of their clients. On the psychology of legal choice making see: G. Low, ‘A Psychology of Choice of Laws’, 24 European Business Law Review 363 (2013); G. Cuniberti, ‘The International Market for Contracts: The Most Attractive Contract Laws’, 34 Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business 455 (2014). , 8xFor a psychological perspective see: R. Salecl, ‘Society of Choice’, 20 A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 157 (2009); B. Schwartz, ‘The Tyranny of Choice’, 290 Scientific American 70 (2004); B. Schwartz, A. Ward, J. Monterosso, S. Lyubomirsky, K. White & D.R. Lehman, ‘Maximizing Versus Satisficing: Happiness Is a Matter of Choice’, 83 Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1178 (2002). , 9xLack of information can be considered also a practical hurdle. To overcome these psychological hurdles, litigants hire lawyers.10xHere I mean both lawyers hired as external experts, or as internal employees of legal entities. The presence of a lawyer in the structure of the legal entity may help to overcome some of these psychological problems. But considering the complicated source of these problems and the nature of the legal reasoning, these lawyers are not enough to overcome all of these psychological hurdles. Lawyers are highly specialised professionals, with experience and knowledge of the law. So, lawyers may be the solution to overcome some of the psychological hurdles and the legal information problems mentioned above, but they also increase litigation costs, making it even more expensive. In cross-border litigation, one lawyer may not even be enough. Often clients hire one lawyer for each jurisdiction they are involved. Therefore, the costs of cross-border litigation may escalate quickly, making it expensive for many and prohibitive for more.

It is suggested that lawyers dominate their clients as a result of six factors. First, legal knowledge is entropic by nature.11xD.M. Engel, ‘Society of Choice’, 2 American Bar Foundation Research Journal 817, at 820-1 (1977). The more time passes the more complicated the interpretation of law becomes. This means that even repeat players see their knowledge become outdated overtime, and even lawyers are obliged to spend more and more time on similar cases. As mentioned earlier, complexity and time are elements that increase the costs of litigation, which means that entropy plays a role in the cost of litigation. Second, a lawyer’s service is a credence good, which is a good produced by an expert, and of which consumers cannot assess the quality and the quantity they need.12xR. van den Bergh and Y. Montangie, ‘Competition in Professional Services Markets: Are Latin Notaries Different?’, 2 Journal of Competition Law and Economics 189, at 193 (2006); U. Dulleck and R. Kerschbamer, ‘On Doctors, Mechanics, and Computer Specialists: The Economics of Credence Goods’, 44 Journal of Economic Literature 5 (2006). This places the producer in a position to dictate what and how much a client should buy. When it comes to legal services, clients can only trust lawyers on what and how much service they will need.13xIt can be questioned at this point whether or not companies with an internal lawyer or legal department can overcome this situation. The answer is yes and no: yes, in case the lawyer is knowledgeable enough and the case is part of this knowledge; no, if the case is complicated and if the lawyer lacks the necessary knowledge. It should be taken into account that lawyers tend to specialise in particular fields of law; and while experts on their field, they may not be able to give an opinion in others fields. But regardless of the position, the lawyer remains the most important element in the choice of court process. Third, lawyers conduct their activities in a superstar type of market.14xG.K. Hadfield, ‘The Price of Law: How the Market for Lawyers Distorts the Justice System’, 98 Michigan Law Review 953, at 972-6 (2000). In these markets, a small difference in quality is reflected in a big difference in earnings. Clients – unaware of the quality and quantity of lawyer service they need – consider lawyers’ fee as an indicator of their quality.15xIt helps in this regards the fact that lawyers are highly specialised and clustered in small speciality groups. See for this J.P. Heinz, E.O. Laumann, R.L. Nelson & E. Michelson, ‘The Changing Character of Lawyers’ Work: Chicago in 1975 and 1995’, 32 Law and Society Review 751, (2006). So large companies and wealthy persons have the tendency to overpay for their legal services. Fourth, the initial lawyer–client relationship develops slowly, but costs increase relatively fast due to the complexity of law, the credence good character of the lawyer’s service, and the superstar type of market lawyers create. These are sunk-costs because they cannot be recovered once incurred. At the beginning, every lawyer has to study a case before offering a strategy or an advice, which creates costs. This initial cost cannot be transferred to another lawyer, and thus it anchors the client to the very first lawyer in many cases. Fifth, a litigation resembles a sunk-cost auction, which means that once a client starts investing in a litigation, the costs escalate so quickly that the only way out of this situation is by investing more in the hope of winning and recovering the costs. Sixth, the market for lawyers resembles a monopoly where natural and legal barriers for entering the market exist.16xL.E. Ribstein, ‘Lawyers as Lawmakers: A Theory of Lawyer Licensing’, 69 Missouri Law Review 299, at 314-5 (2004). These barriers make it (relatively) difficult to enter the market. Furthermore, natural barriers, such as the possibility to acquire meaningful professional knowledge, restrict the number of available lawyers for a certain type of case. For example, any large law firm that has been dealing with international commercial cases has been collecting knowledge as well. This knowledge remains with the firm and helps it to accumulate even more of it. It becomes, therefore, difficult for other lawyers to enter this specific market without that specific knowledge. Other barriers like education requirements, availability of this education, qualification costs, bar membership requirements, and so forth further increase the difficulties to enter the market, emphasising its resemblance with a monopoly.

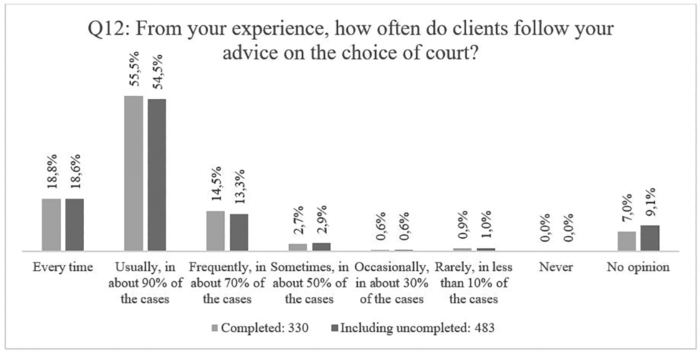

The concurrence of these factors puts clients in a disadvantageous position. They search for a service often unsure of the quality and quantity they want, while costs escalate quickly, and the possibility to withdraw becomes more expensive. Lawyers benefit from this situation to dictate litigation plans and choice-of-court strategies, which makes them the true output source of the lawyer–client relationship. A relatively small group of lawyers working for the biggest law firms can be expected to be the most experienced in dealing with international commercial cases. Empirical evidence seems to confirm these findings. Results from the survey I conducted on lawyers (described hereunder) show that 45.7 per cent of the respondents discuss the choice of court with their clients in less than 50 per cent of the cases. When it comes to choice-making, only 28.1 per cent of the respondents have experience of clients making the choice, and the rest consider that they (lawyers) make the actual choice. In addition, respondents were asked to indicate how often clients followed their advice when making a choice of court (Question 12, chart hereunder), and 91.5 per cent of them responded that clients followed their advice in 70 per cent or more of the cases. Evidently, the empirical results at hand support the theoretical claim that lawyers dominate their clients and are the real choice-of-court makers in many situations.

2.2 Lawyers’ Choice-of-Court Preferences in the EU – Empirical Evidence

2.2.1 Methodology and Approach to the Study

Most of the previous surveys on choice of law or choice of forum have been conducted on business representatives or companies, with few having lawyers as respondents.17xL.G. Moser Meira, ‘Parties’ Preferences in International Sales Contracts: An Empirical Analysis of the Choice of Law’, 20 Uniform Law Review 19 (2015); T. Eisenberg and G. Miller, ‘The Flight to New York: An Empirical Study of Choice of Law and Choice of Forum Clauses in Publicly-Held Companies’ Contracts’, 30 Cardozo Law Review 1475 (2008-2009); G. Cunibertit, ‘The Laws of Asian International Business Transactions’, 25 Washington International Law Journal 35 (2016); G. Cunibertit, ‘The International Market for Contracts: The Most Attractive Contract Laws’, 34 Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business 455 (2014); S. Vogenauer, ‘Regulatory Competition through Choice of Contract Law and Choice of Forum in Europe: Theory and Evidence’, European Review of Private Law 13 (2013); S. Sanga, ‘Choice of Law: An Empirical Analysis’, 11 Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 894 (2014). , 18xAmong the surveys organised on lawyers: P. Durand-Barthez, ‘The “Governing Law” Clause: Legal and Economic Consequences of the Choice of Law in International Contracts’, International Business Law Journal 505 (2012). The above analysis, however, shows that the real choice makers are lawyers, and in particular lawyers working in large law firms. Considering this, I conducted a survey on this type of lawyers for their choice-of-court preferences.19xAs mentioned, the survey was conducted in the ambit of a previous study. See n. 3. I selected the top law firms on the basis of their revenues in the EU. For this I used two lists, namely, one from The American Lawyer,20x The American Lawyer, October 2014. which lists the top one hundred law firms in the world in terms of revenue, and the other is the list of the top one hundred law firms in Europe (excluding British and American law firms) as drawn by the Lawyer.21xThe Lawyer, periodically, publishes the European 100 Report, which is an analysis of the market for lawyers in the EU and focusing only on the continental law firms. For this survey, I used data from the 2014 Report. See for the updated version: https://www.thelawyer.com/reports/european-100-2018-report/ (last visited 8 February 2019). I could not distinguish between lawyers knowledgeable or experienced enough and those with insufficient or little knowledge in the choice-of-court issues because lawyers’ biographies were not always available and not always detailed enough. I decided to distribute the survey to all the lawyers working in these law firms, inviting only those who have experience in choice-of-court matters to respond. From the websites of these law firms, I collected the individual email addresses of all their lawyers working in the EU, to which I sent an email inviting them to take part in the survey. I received 529 responses, of which 330 completed, while the rest had different degrees of incompleteness. The survey was conducted between October and November 2015.

2.2.2 Demographics

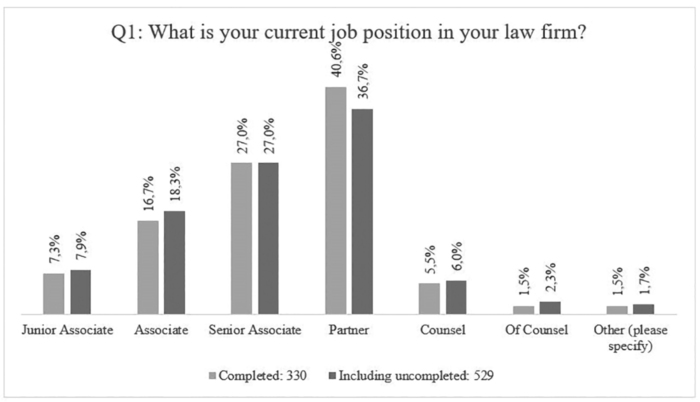

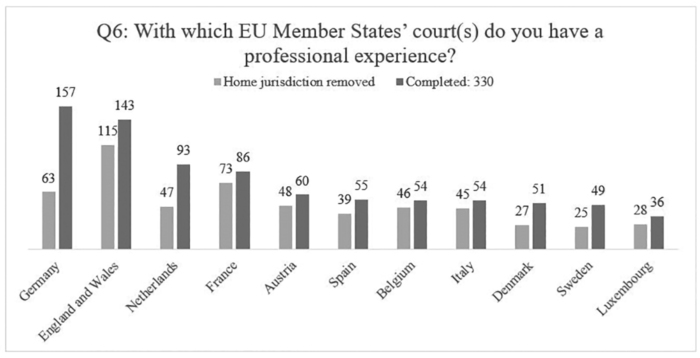

Results from the survey show that the majority of the respondents were partners (40.6 per cent) or senior associates (27 per cent) in their firms.22xCompared to Junior Associates with 7.3 per cent, and Associates with 16.7 per cent. In addition, 70.6 per cent of the respondents had more than six years of experience in their job, where 57.27 per cent of them had more than eleven years of experience. These results indicate that most of the respondents held senior positions and had considerable experience in their job. Their senior position is significant because they are often team leaders who control and design the strategies of larger groups of lawyers; furthermore, they are among the most experienced in their firms when it comes to choice-making. For the majority of the respondents (65.1 per cent), choice of court was also a frequent activity. When asked where they conducted most of their professional activity, 28.48 per cent of the respondents answered Germany, followed by the Netherlands (13.94 per cent), and England and Wales (8.48 per cent). Despite their seat, the vast majority of the respondents reported a full professional proficiency in English (76.7 per cent). This is interesting for three reasons. First, it is a further evidence that English is the lingua franca of international trade and business. Second, it further justifies why the new courts offer proceedings in English. Third, it is a hint that the legislation and the administrative bodies surrounding an international commercial court should be available in English so as to further facilitate the ability of foreign lawyers to familiarise with a jurisdiction. Respondents were also asked to mention the courts with which they have had a professional experience. Most of them reported experiences with the English, French and German courts. Using the data from this question, it can be calculated that lawyers have experience with an average of 3.23 courts, which can be reduced to 2.23 if their home jurisdiction is removed. In other words, it can be expected that a professional lawyer knows from a first-hand experience only two courts. While this is not per se negative, it shows that lawyers tend to have only a limited practical knowledge of foreign courts.

2.2.3 Choice-of-Court Preferences

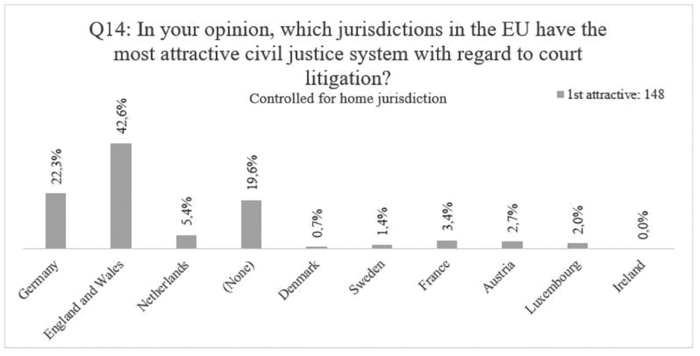

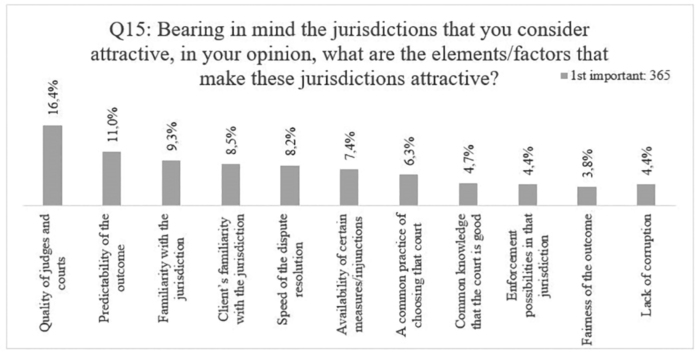

The central part of the survey asked respondents to mention the most attractive court in the EU (Question 14). To eliminate any home bias, I removed from the answers the respondents’ home jurisdiction. After this operation, England and Wales (42.6 per cent), Germany (22.3 per cent), and the Netherlands (5.4 per cent) were the most preferred jurisdictions.23xThese results are comparable with the results of the Vogenauer (see n. 17) and the Lein surveys (see n. 2), thought the target population is different. The most attractive elements of these courts (Question 15) were ‘quality of judges and courts’ (22.3 per cent), ‘predictability of the outcome’ (11 per cent) and ‘the familiarity [of the respondent] with the jurisdiction’ (9.3 per cent). Most of the factors can be categorised as either having to do with the intrinsic quality of the judicial system (‘quality of judges and courts’, ‘predictability of the outcome’, etc.) or having to do with how it is perceived (‘familiarity with the jurisdiction’, ‘a common practice of choosing that court’, etc.).

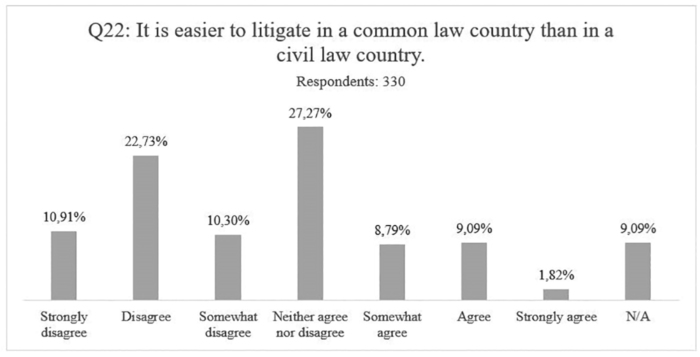

Frequently, choice of court is made together with the choice of law. Parties match the law and the court of a jurisdiction in order to reduce complexity. It becomes more complex if a foreign law is interpreted by a foreign judge. Considering this, I asked respondents which was more important during the choice of court, substantive law or procedural law (Question 13). Results do not provide a clear answer, but preferences lean on the substantive law side, which may indicate that choice of court follows the choice of law. In addition, I asked respondents to reflect on the differences between common law and civil law and in which of them it was easier to litigate. These questions are important considering that it is often mentioned that an advantage of London is the use of common law compared with the civil law of continental Europe. Respondents agree (Question 21) that the differences between common law and civil law are considerable, but they disagree that it is easier to litigate in a common law country compared with a civil law country (Question 22). These results seem to indicate that the difference between civil and common law is not that important in making a choice of court.

2.2.4 Analysis

On the basis of the results of the survey, it can be said that lawyers have two groups of preferences: one is litigation service related, and the other is court perception related. Results from the survey hint that court perception preferences are very important, and perhaps more important than litigation service preferences.24xFor this, consider also the surveys of Durnad-Barthez, and Vogenauer. Above n. 17 and 18. For example, according to the civil justice part of the Rule of Law Index (RLI), England (as the United Kingdom) is fourteenth in the world and eighth in Europe.25xIn the EU, England ranks seventh after Netherlands, Denmark, Germany, Sweden, Finland, Austria, and Estonia. RLI data can be accessed at http://data.worldjusticeproject.org/#table (last visited 8 February 2019). Also an analysis of the EU Justice Scoreboard shows that the United Kingdom’s civil judicial system ranks seventh in the EU.26x See n. 3, at 245. In view of these results, England appears to have a qualitative judicial system, but certainly not the best in the EU. One can rebut that England has the best (international) commercial courts in Europe; however, there is no evidence for this. So, while England does not have the best judicial system, it seems that lawyers’ perception about its courts is of a relatively high level. In fact for respondents, ‘familiarity with the jurisdiction’, ‘client’s familiarity with the jurisdiction’, and ‘a common practice of choosing that court’ are some of the most attractive elements that indeed have little to do with the intrinsic qualities of the system and more with how it is perceived.27xAlready, the research of Lein was suggesting this for a different group of respondents. See Lein n. 2. Indeed, evidence seems to support this claim. Results from Question 6 of the survey show that most of the respondents reported professional experiences in England. This number is almost double compared with that of the second-placed Germany, which speaks of the familiarity that lawyers (and perhaps their clients) have with England. According to the results from Question 20, the majority of the respondents (69.9 per cent) considered England to actively trying to attract litigants in its court system, the Netherlands and Germany are second and third with 23.9 per cent and 23.1 per cent of the responses, respectively. Furthermore, the Law Society of England and Wales continually promotes London’s courts in international events.

In sum, lawyers consider two groups of preferences when making a choice of court: one is the litigation service preferences, and the other is court perception preferences. The case of England, which is the most attractive jurisdiction in the EU, shows that court perception preferences are very important. In fact, considering that the quality of English courts is not better than many others in Europe, perception seems to be essential to its success. For the new courts, therefore, it is important not only to be highly qualitative, but also to be perceived positively. If the system where they are embedded does not have a sufficiently positive perception, the new courts should try to improve this. If they do not improve this court perception, their success is at risk. -

3 Strategies of the New International Commercial Courts

The previous section demonstrated that in some situations lawyers may dominate their clients, and when it comes to the choice of court chances are high that they will be the one to take the decision. On the basis of the results of the survey, lawyers seem to have two types of preferences when it comes to cross-border courts: one includes those related to the litigation service of the court, while the other one includes court perception preferences. To be successful, the new courts’ offer should match these preferences. The new courts, however, can respond only to some of the preferences of lawyers, for example, ‘quality of judges and courts’, ‘predictability of the outcome’ or ‘speed of the dispute resolution’. Other preferences, such as ‘familiarity of the jurisdiction’, ‘enforcement possibilities in that jurisdiction’ or ‘a common practice of choosing that court’, can be related only to the quality and reputation of the jurisdiction where the new court is established. To assess whether or not the new courts will match the preferences of their potential users, it becomes important to consider not only their offer but also the health of the judicial system where they operate. This section takes on this task. It provides an overview of the judicial system where each new court operates, focusing on the particular elements that fulfil the preferences of parties when making a choice of court; in addition, it makes on overview of how the offer of the new courts matches the preferences of their potential users. To assess the offer of each judicial system, I use data from the EU Judicial Scoreboard (Scoreboard) and the Rule of Law Index (RLI) with a particular attention on the elements considered important by potential court users. I highlight, therefore, how attractive the new courts would look for prospective court users. Despite being part of the bigger competitive picture, I omit England from this analysis because it does not offer a new court, but, instead, promotes its already existing judicial system.

The EU Judicial Scoreboard is a collection of data related to the civil justice system of each EU Member State. In the words of the Commissioner for Justice Věra Jourová ‘… it helps Member States to address the challenges they are facing with their justice system’.28xForeword to the 2018 EU Justice Scoreboard. Despite the name there is no ranking of the best or worst jurisdiction. This has never been the aim of the Scoreboard. Data collected by each Member State are organised and reported into categories, with figures being the smallest unit that report data. In each figure, Member States are ranked on the basis of their performance. Every figure provides relative29xRelative because it is difficult to find a reference frame in which to assess the importance of the data. In absence of any reference frame, data from different Member States can be compared with each other to consider the relative health of each Member State in relation with the others. data about the health of each Member State; I use the ranking in some of the figures to consider the general offer that the new courts provide. The Rule of Law Index is a study organised by the World Justice Project, a not-for-profit organisation based in the United States. As the name suggests, the RLI collects data on several factors that influence the rule of law in each of the jurisdictions it studies. One of the factors considered is civil justice, for which seven sub-factors are considered.30xThese sub-factors are ‘Accessibility and affordability’, ‘No discrimination’, ‘No corruption’, ‘No improper government influence’, ‘No unreasonable delay’, ‘Effective enforcement’, and ‘Impartial and effective ADRs’. Data from the civil justice factor of the RLI are used hereunder to consider the general outlook of the new courts’ judicial system.

Some criticism about these instruments exits. Both the Scoreboard and the RLI remain quantitative studies with little qualitative insight. Furthermore, the data they provide come with little context, which can be misleading. Despite the lacunae, both the Scoreboard and the RLI are unique in their task, and provide a compilation of data helpful in quantitative longitudinal and in-depth studies. The analysis, hereunder, refers only to some of the figures of the Scoreboard, in particular, Figure 5 (‘Number of incoming civil and commercial litigious cases’), Figure 8 (‘Time needed to resolve litigious civil and commercial cases’), Figure 16 (‘Number of pending litigious civil and commercial cases’) and Figure 59 (‘Businesses’ perception of judicial independence’).

The next section reports data from the Scoreboard and the RLI for each of the new courts’ jurisdictions. It makes an inventory of the offer of the new courts together with the judicial system where they are embedded. In Section 3, the results of this inventory will be compared with the lawyers’ preferences to understand how much the offer of the new court matches them.3.1 Belgium – Brussels International Business Court

Belgium scores eighteenth in the world for the civil justice factor of the RLI, with high results on all the sub-factors but the ‘no unreasonable delay’. Compared with the other Member States considered in this study, Belgium scores better than France, but lower than the Netherlands and Germany. Compared with the EU and EFTA31xEuropean Free Trade Association includes Iceland, Lichtenstein, Norway, and Switzerland. and North America, Belgium ranks eleventh out of twenty-four jurisdictions. Compared with developed countries, Belgium is rather average with no clear excellence.

Data from the Scoreboard (Figure 5) show that Belgian courts receive a relatively high number of civil and commercial litigious cases. Only Romania has higher figures. It is obvious to think that the high number of cases may play a role in the ability of the Belgian courts to resolve them. Surprisingly enough, Belgian courts are the fastest in the EU in resolving litigious civil and commercial cases (Figure 8). While this is true for the first instance courts, data from third instance court show that these are amongst the slowest (seventh place from the bottom, Figure 9). It can be argued that part of the large number of cases that are resolved by the first instance courts reach the higher courts, which do not have the capacity to process this volume and thus create delays and case backlog. As a result, the number of pending cases in Belgium is somehow average compared with other EU Member States (Figure 16), and while better than France, it is not as good as the Netherlands or Germany. As regards independence, businesses consider Belgian courts to be more independent than those of Germany or France. Belgium ranks ninth in this figure compared with the second-ranked Netherlands, and the third-placed United Kingdom.

Belgium is the last actor to enter the competition to attract international commercial cases and the race to create a special court for this. As mentioned in the introduction, Belgium plans to create the Brussels International Business Court (BIBC). The prominent characteristics of the BIBC will be as follows: (a) court proceedings will be held in English; (b) the court will be composed of a judge supported by two lay judges selected among experts in the field of dispute, and lay judges may also be non-Belgian nationals; (c) proceedings will be conducted according to the UNCITRAL Model Law on international commercial arbitration; (d) the possibility of appeal will be limited only to cassation; and (e) court fees will be relatively high.32xThe bill can be accessed at the official page of the Belgian parliament: http://www.dekamer.be/doc/flwb/pdf/54/3072/54k3072011.pdf (last visited 8 February 2019).

The draft law suggests that the BIBC is trying to avoid any association with the current court system in Belgium.33xThis is also accepted in the bill. In particular see page 10-11. It does this in offering a new procedure that is, UNCITRAL Model Law, a special composition of the judging panel, and the absence of appeal. These may address three issues related to the Belgian courts. The first one is the relative slow pace at which commercial cases are resolved in Belgium’s higher courts. Reducing the possibility to appeal provides parties with a final decision, but more importantly it gives the impression that court proceedings are fast and to the point. The second issue is the quality of judges. The BIBC will have in its offices selected judges, probably among the best in Belgium. These judges will be supported, case by case, by lay judges with considerable experience in the field.34xSelecting the best judges to sit in the courts and supporting them with lay judges with a high reputation in field may be very productive according to Coyle. This is often mentioned as a success factor for arbitration. J.F. Coyle, ‘Business Courts and Interstate Competition’, 53 William and Mary Law Review 1915, at 1972-1973 (2012). The final issue is the relative obscurity of the Belgian courts. Data from the survey, analysed in Section 1, show that few lawyers are familiar with the Belgian courts. These data in conjunction with the data on lawyers’ preferences when choosing a court, suggest that any new court aspiring to attract cross-border commercial cases should create a fan base. And this fan base can be created more easily by providing them with a set of rules that is relatively ‘famous’, in this case the UNCITRAL Model Law. However, this is only one facet of the same object, which includes familiarity with the court, common knowledge that the court is good, and a common practice of choosing that court, which do not seem to be addressed by the BIBC project.3.2 Germany – Chambers for International Commercial Disputes

In the civil justice factor of the RLI, Germany ranks third in the world, and in the EU, EFTA, and North America subgroup, with above-average high scores in each sub-factor. In particular, the German civil justice scores high in the ‘No corruption’, ‘No improper government influence’, and ‘Effective enforcement’ sub-factors. Only the Netherlands and Denmark score better than Germany in the RLI ranking. Data from the Scoreboard show that Germany has relatively few incoming civil and commercial litigious cases (Figure 5). This number is higher compared with the Netherlands, but lower compared with Belgium and France. German courts are on the median line for the time needed to resolve civil and commercial cases, when it comes to both first instance (Figure 8), and higher instance (Figure 9). The speed of the German courts is reflected in the low number of pending cases (Figure 16), which is higher than the Netherlands, but lower than Belgium and France. Businesses’ perception of judicial independence in Germany has been constantly falling from 2010 to 2017 (Figure 59). It is not clear why this is happening, but it may require some attention from the government.

Data from both the RLI and the Scoreboard may be interpreted to show that German courts are better than those of France and Belgium, but not better than those of the Netherlands. Germany seems to score relatively high on the time needed to resolve a dispute, although the fall of the “independence perception” needs to be addressed. Fast courts give the impression of an efficient court, which is also what the brochure ‘Law Made in Germany’ claims.35xLaw Made in Germany is a brochure prepared and published by a consortium of German institutions, which promote the German legal culture including law and courts. It is also served by a dedicated website: https://www.lawmadeingermany.de/ (last visited 8 February 2019). It should be added, though, that the fact that cases are resolved relatively fast in German courts does not mean that they are efficient; other factors may be important here.36xFor instance better resources, better trained lawyers, more human resources in courts, etc.

Germany’s attempt to create a special setting for international commercial disputes is rather complicated. Some attempts to create special English-speaking sections in certain courts have failed.37xIn 2010, the courts of Cologne, Bonn, and Aachen created a project to use English as the language of oral proceedings in case parties would ask for it. The attempt was not very successful because apart from the oral part, the rest of the process was in German. https://www.lto.de/recht/hintergruende/h/modellprojekt-in-nrw-lg-koeln-goes-international/ (last visited 8 February 2019). The failure may be attributed to Article 184 of the Courts Organisation Act, which requires the use of German during court proceedings.38x“Gerichtsverfassungsgesetz in der Fassung der Bekanntmachung vom 9. Mai 1975 (BGBl. I S. 1077), das zuletzt durch Artikel 1 des Gesetzes vom 12. Juli 2018 (BGBl. I S. 1151) geändert worden ist”. To overcome this, the proponents of the chambers for international commercial disputes have put forward amending the Courts Organisation Act with the intention to allow parties to use English in these special chambers.39xDeutscher Bundestag, Entwurf eines Gesetzes zur Einführung von Kammern für Internationale Handelssachen (KfiHG), Drucksache 19/1717 of 18 April 2018, Begründung, at 8-10 available at http://dipbt.bundestag.de/dip21/btd/19/017/1901717.pdf (last visited 8 February 2019). Other parts of the proposal focus on time management, and a streamlined and predictable process. Apart from this proposal, which attempts regulation on a national level, on regional level the ‘Frankfurt Justice Initiative’ seems to be the most advanced. This Initiative was started by a group of academics and lawyers with the support of the Minister of Justice of the Federal State of Hessen.40x http://conflictoflaws.net/2017/the-justice-initiative-frankfurt-am-main-2017-law-made-in-frankfurt/ (last visited 8 February 2019). The aim of the Initiative was to capitalise from the possible litigation migration from post Brexit London, the position of Frankfurt as an international financial hub, and the good reputation of the German courts. An achievement of the Initiative was the creation of the Chamber for International Commercial Disputes at the Lower State Court in Frankfurt (Landgericht Frankfurt am Main), which in its own words ‘was established to create an attractive forum for cross-border disputes of English-speaking parties allowing them to benefit from Germany’s reliable and expeditious public dispute resolution mechanisms and highly efficient enforcement mechanisms’.41x https://ordentliche-gerichtsbarkeit.hessen.de/ordentliche-gerichte/lgb-frankfurt-am-main/lg-frankfurt-am-main/chamber-international (last visited 8 February 2019).

Germany’s court system health seems to be better than most of the other Member States in Europe. Considering the data from the survey analysed in Section 1, Germany is the jurisdiction where lawyers have more experience after England and Wales, while its courts report fast proceeding times. These are some of the most important ingredients for creating an attractive jurisdiction for international commercial courts. In addition, Germany has a strong export-oriented economy, with a potential for cross-border litigation. What Germany lacks, in my opinion, is more aggressive promotion of its system and a different approach to establishing international commercial courts. Perhaps, it would be better to establish a single commercial court at federal level instead of courts at state level, though this may be more challenging from the legislative point of view. A positive aspect of this idea is that such a court would accumulate experience and a fan base faster than a multitude of small courts. Furthermore, it would concentrate the most talented judges in a single place, providing a more attractive venue, while reducing competition between the different federal states.42xJudges concentration is similar to what was already mentioned in n. 30 above. As it was the case with Belgium, Germany lacks a clear strategy to promote its new courts. It may be too soon to think about this considering that the proposal is still under scrutiny in the Parliament, but strategies that target lawyers’ court perception are of considerable importance as the above analysis showed.3.3 France – International Chamber for Commercial Disputes

Based on the results of the RLI, France’s civil justice is twenty-second in the global ranking, and thirteenth in the EU, EFTA, and North America group. France ranks better than Belgium, but worse than the Netherlands, Germany, and the United Kingdom. France seems to have a low score in the ‘No discrimination’ subgroup, while the score in the other subgroups is high. Relative to the other Member States, French courts receive an average number of civil and commercial litigious cases, which is lower than that of Germany and the Netherlands, but higher than that of Belgium. However, French courts seem to be relatively slow, being almost at the bottom of the table, for the time needed to resolve litigious civil and commercial cases (Figure 8). This situation does not improve even if the first, second, and third instance are considered (Figure 9). In both these figures, France is the last from the jurisdictions studied in this article. The slow processing time reflects also in the number of pending cases (Figure 16), which is the sixth highest in the EU. France, however, has a similar score with that of Germany when it comes to businesses’ perception of judicial independence, but compared with Germany the perception is improving and not deteriorating.

In February 2018, the Court of Appeal of Paris inaugurated a special chamber for international commercial disputes.43xThe protocol that establishes this chamber: https://www.cours-appel.justice.fr/sites/default/files/2018-06/CICAP_English_Protocole%20barreau%20de%20Paris%20-%20Cour%20d’appel%20de%20Paris_mai2018.pdf (last visited 8 February 2019). This special chamber will serve as second instance to the already existing International and European Chamber of the Paris Commercial Court.44xThe protocol: https://www.cours-appel.justice.fr/sites/default/files/2018-06/CICAP_EnglishVersion_Protocole%20barreau%20de%20Paris%20-%20Tribunal%20de%20commerce%20de%20Paris.pdf (last visited 8 February 2019). The main features of these chambers are the use of English in documentary evidence (procedural acts will be drafted in French) and during hearings, which will have a bigger place in the process – inspired by the common law tradition. Court decisions will be issued in French, accompanied by a sworn translation in English. Said features have been agreed between the courts of first instance and appeal, and the bar association of Paris. From a positive perspective, French courts and lawyers, with this agreement and the blessing of the Ministry of Justice, have avoided the legislative path that goes through the parliament.45x See the article from Biard in the same issue of this journal. A. Biard, ‘International Commercial Courts in France: Innovations Without Revolution?’, Erasmus Law Review (2019). From a negative perspective, this solution may be pragmatic, but legal certainty may be affected here. Considering that the use of English before the courts is based on a memorandum of understanding between the courts and the bar of Paris, parties may contest the use of English during court proceedings as a violation of French law and Constitution.46xE. Jeuland, ‘The International Division of the Paris Commercial Court’, 4 Tijdschrift voor Civiele Rechtspleging 143, at 144 (2016).

France is one of the strongest economies in the EU, and also the centre of many international organisations and companies. The prospect of Brexit in conjunction with the need to offer a premium service to international commercial litigants resulted in a renovation of the existing international commercial chambers. Supposedly, Brexit provides a financial opportunity to attract litigants migrating from the London courts, while financial opportunity provides a reason for creating new streamlined court procedures. In fact, if the new procedures agreed between the Parisian courts and the bar association can improve the performance of the French courts, the later ones can become very attractive to international commercial litigants. On the positive side, France is the second jurisdictions with which lawyers have the most experience after the first-placed England and Wales.47xQuestion 6 from the Survey. This fact plays an important role considering that ‘familiarity with the court’ and ‘a common practice of going to that court’ are two of the elements that influence choice of court for lawyers. Another positive factor of the French courts is their early start, which may have created a fan base or ‘a common practice of going to that court’, which may be detrimental to fend off the new emerging courts from Belgium, Germany or the Netherlands.3.4 The Netherlands – The Netherlands Commercial Court

The Netherlands has the best civil justice system in the world according to the RLI, with a very high score on all the subgroups, in particular in ‘no corruption’ and ‘no improper government influence’ subgroups. Data from the Scoreboard show that the Netherlands receives a relatively low number of civil and commercial cases, which is almost seven times less than Belgium and almost two times less than Germany (Figure 5). This low number of incoming cases may play a role in the short amount of time needed to resolve them. Figure 8 shows that Dutch courts are relatively fast when the first instance is considered, surpassed only by Belgium, Latvia, and Luxembourg. The same can be said for the number of pending litigious civil and commercial cases, which is the fourth lowest in the EU (Figure 16). Furthermore, the Netherlands is the second Member State with the highest perception of judicial independence by companies (Figure 59). Considering the RLI and the Scoreboard, it is clear that the Netherlands scores not only better than Belgium, Germany, and France, but also better than the United Kingdom.

Having this in mind, the First Chamber of the Dutch parliament approved the law for the establishment of the Netherlands Commercial Court (NCC) on 11 December 2018.48xG. Antonopoulou, E. Themeli and X.E. Kramer, ‘No fake news: the Netherlands Commercial Court proposal approved!’, http://conflictoflaws.net/2018/no-fake-news-the-netherlands-commercial-court-proposal-approved/ (last visited 8 February 2019). The NCC opened its doors on 1 January 2019 as a special chamber of the District Court of Amsterdam, which is specialised in resolving international commercial disputes in English. Parties should specifically agree to go to this court for resolving their disputes. Court fees are higher compared with the normal court to justify the special organisation and special procedural rules created for this court. The aim of these rules is to improve efficiency, and to offer case management in a case-by-case approach.49x See also the bill on the NCC ‘Reglement voor de internationale handelskamers van de rechtbank Amsterdam (NCC District Court) en het gerechtshof Amsterdam (NCC Court of Appeal)’ available at: https://www.rechtspraak.nl/SiteCollectionDocuments/concept-ncc-reglement-juni-2018.pdf (last visited 8 February 2019). One positive aspect of the NCC proposal is that it requires some marketing plans.50x See the article from Bauw in the same issue of this journal. E. Bauw, ‘Commercial Litigation in Europe: In Transformation: The Case of the Netherlands Commercial Court’, Erasmus Law Review (2019). If perhaps these marketing plans would suggest also activities that tackle the court perception of lawyers, it may pave the road to success for the NCC.

Considering the high score of the Netherlands, it seems difficult to find an area of improvement for the Dutch courts. However, the Dutch should not rest on laurels and should consider also that the success of the NCC depends also on how it is perceived. Attracting cross-border litigants requires considerable effort, which the NCC’s promoters seem to acknowledge. But more effort will be needed to establish a common practice of choosing this court. Two factors may be essential here, one is Brexit and the possible migration of litigation from England to other EU jurisdictions, and the second is the fact that the Netherlands is one of the most preferred jurisdictions for registering a company. The hope here is that companies registered in the Netherlands may bring cases to the NCC, and perhaps Brexit and the proximity of the Netherlands with England may also play a positive role in this respect. -

4 Conclusions: Matching Preferences and Courts

This article argues that the new courts in Belgium, Germany, France, and the Netherlands do not seem to properly address users’ court perceptions. Section 1 showed that large and medium companies, assisted by their lawyers, are the most probable users of the international commercial courts. Lawyers and not clients are responsible for the choice of court as a result of the service type they provide, the qualities of the market for lawyers, and some other factors created as a combination of these two. In fact lawyers dominate their clients. This conclusion was confirmed by the findings of my survey, where lawyers responded that clients follow their suggestion or leave it to them to make the choice-of-court decision. Results from the aforementioned survey show that England and Wales is the most preferred jurisdiction for international commercial litigation for lawyers. For them the quality of judges, lack of corruption, and neutrality are the most important factors when choosing a court. In addition, factors such as familiarity with the court, client’s familiarity, a common practice of choosing that court, and a common knowledge that the court is qualitative play an important role. Lawyers’ preferences can be grouped in two: one is the group of preferences related to the litigation service, and the other is the group of preferences related to the perception of the court.

Some preferences have to do with the characteristics of the jurisdiction where the new court is located rather than new court itself. Section 2 suggested that the new courts – as international commercial litigation venues – together with the jurisdiction where they operate should match lawyers’ preferences if they want to be successful. This article argues that the new courts do not match the preferences of lawyers, and in particular court perception preferences. To argue this, I made an inventory of the offer of the new courts and their jurisdictions in the second section. Data from the RLI and the Scoreboard were used to assess the quality of these jurisdictions. According to the RLI, the Netherlands has the best judicial system in the world, followed by Germany, Belgium, and France. France suffers in all the analysed figures of the Scoreboard, while the Netherlands is often among the top five EU jurisdictions. I have left England outside of this analysis because even though being a competitor it does not create any new court. In addition, I briefly described the design of the new courts, pointing out their respective strong points, in particular those that would make them attractive to lawyers. The results of this analysis are summarised in Table 1.Table 1 New courts and preferred court elementsBE DE FR NL Quality of judges and courts n e n e n Predictability of the outcome n n n n Familiarity with the jurisdiction e e Client’s familiarity with the jurisdiction e e e Speed of the dispute resolution e n e n e n A common practice of choosing that court e e Common knowledge that the court is good n Enforcement possibilities in that jurisdiction e e Fairness of the outcome e n n e n e = existing measures, n = measures of the new court

Preferences related to lawyers’ court perception are marked in italics.Summarising the analysis, Table 1 shows that the civil system of some jurisdictions already match certain preferences of international commercial lawyers (marked with ‘e’). For example, the RLI shows that the Netherlands has already a good quality of judges and courts. This does not mean that Belgium and France have low-quality judges and courts, but they are not of the same level. Yet another example, results from the survey suggest that there is a stronger common practice of going to Germany and France to litigate international commercial disputes, compared with Belgium and the Netherlands, but way weaker compared with England. Next to the already existing attributes of the judicial systems in Table 1, I have added which one of the preferences are addressed by the new courts (marked with ‘n’). Evidently the new courts address important issues such as speed of dispute resolution, predictability of the outcome, and fairness of the outcome. For example, the BIBC aims at a streamlined process, which should be able to resolve a dispute very fast. Or the fact that the new courts aim at a new structure with ‘handpicked judges’ shows that they want to increase the quality of judges and courts. What is missing in these projects is a plan to address the group of preferences related to lawyers’ court perception (marked in italics). While the promoters of these new courts may be aware (e.g. the Netherlands) of the need to ‘convince’ lawyers to use these courts, it is hard to see any strategy or attempt to promote them. Most emblematic is that all the activities of the ‘Frankfurt Justice Initiate’ have been held in German in Germany, while the court is intended to be international and in English. It can be argued that these activities aimed at convincing the local legal community of the need of such a court; however, the international community deserves attention as well. As opposed to this approach, England actively promotes its jurisdiction on a global level and mostly to lawyers. Perhaps the promotion of its courts, combined with a tradition to go to London to litigate, and a qualitative judicial system is the key of the English success. Perhaps the outlook is as important as the substance – a lesson that the new courts should learn fast if they want to succeed.

In sum, the new courts and their supporting jurisdictions seem to offer what the international commercial litigants want. However, they do not seem to do much about court perception–related elements. It remains to be seen if this will change in the future; otherwise, the new courts increase the chances of not succeeding in this race. -

5 Final Remarks

This article shows that some jurisdictions in the EU are at different stages of creating international commercial courts, with the aim of attracting cross-border litigants. While the new courts are an improvement compared with the local courts, they should do more to change the perception of lawyers about them. In this final section, I want to address the issue of Brexit and conclude this article with two recommendations.

As it was mentioned, the new courts consider Brexit as an opportunity to carve out for themselves a piece from the English pie. Brexit therefore serves two functions. It is not only a catalyst for making haste to create the new courts, but also a new opportunity of profit for them. So while, Brexit is not the reason for building the windmill of the new courts, it certainly is the wind that moves their sails. What is going to happen remains rather speculative, but according to a Thompson Reuters report, English lawyers think that their workload will decrease after Brexit, while European lawyers think that their workload will increase.51xThompson Reuters®, ‘Catalyst or Catastrophe? How Brexit Will Impact Law Firms’, (2018), Thompson Reuters®, London. Some respondents from the same survey suggest that, after Brexit, cases may migrate from London’s court to arbitration. However, arbitration lawyers remain sceptic about this idea. A survey, organised by White & Chase and Queen Mary University of London, found that lawyers think that London will survive as the main seat where to conduct arbitration in Europe, but no increase in the workload can be expected.52xWhite&Chase® and Queen Mary University London, ‘2018 International Arbitration Survey: The Evolution of International Arbitration’, (2018), White&Chase® and Queen Mary University London, London. Interestingly, this survey finds that lawyers prefer London firstly for its reputation and secondly for being neutral and impartial. As suggested by the results of this survey, but also by the analysis in this article, reputation, perception, and image play an important role in choosing a forum. It is therefore advisable for the new courts to consider the following suggestions.

First, competing jurisdictions should not only try to promote their courts as if they were a product, by highlighting the benefits and the gains compared with other competitors, but also change the perception lawyers and their clients have of their jurisdiction. Second, the new courts should try to make local lawyers their clients habituels so that habit and common knowledge is created in a community, which can later be exported abroad. If the new courts would also pay attention to these points, they will have more chances to beat England at their own game. - * This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 726032). Information on the ERC consolidator project ‘Building EU Civil Justice: challenges of procedural innovations – bridging access to justice’ is available at http://www.euciviljustice.eu/.

-

1 From the website of the Netherlands Commercial Court: ‘[…] to create a baseline that judges, lawyers and parties can easily refer to’ (See the website of the NNC: https://www.rechtspraak.nl/English/NCC (last visited 8 February 2019), or the International Chamber of the Paris Court of Appeal […] il est unanimement estimé que pour se rapprocher des standards internationaux, il serait indispensable que nos juridictions répondent, mieux qu’elles ne le font actuellement, aux impératifs de délais exigés pour la resolution des affaires aux enjeux financiers importants.’ (Haut comité juridique de la place financière de Paris, ‘Preconisations sur la mise en place à Paris de chambres specialisees pour le traitement du contentieux international des affaires’, (2017), HCJP, Paris).

-

2 S. Vogenauer, ‘Regulatory Competition Through Choice of Contract Law and Choice of Forum in Europe: Theory and Evidence’, European Review of Private Law 13, at 53-60 (2013); E. Lein, R. McCorquodale, L. McNamara, H. Kupelyants & J. del Rio, ‘Factors Influencing International Litigants’ Decisions to Bring Commercial Claims to the London Based Courts’ (2015), Ministry of Justice, London.

-

3 This survey was conducted during my PhD studies. Results of this study were published in: E. Themeli, Civil Justice System Competition in the European Union (2018), at 266-304.

-

4 In the European Union, parties can make a choice of court agreement, which are regulated by Art. 25 of the Brussels I (recast) Regulation (Regulation (EU) No. 1215/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 December 2012 on jurisdiction and the recognition and enforcement of judgments in civil and commercial matters OJ L 351, 12 December 2012, page 1-32). According to it, parties have considerable freedom to choose any of the courts in the EU despite their domicile or connecting factors with the chosen jurisdiction. Despite some restrictions – for example, the exclusive jurisdiction conferred to some courts by Art. 24 – Art. 25 gives European courts a global reach; it allows even parties with no connection to the EU to litigate in the courts of its Member States. In matters relating to insurance, consumer contracts, and individual contracts of employment choice of court agreement is regulated by Arts. 15, 19, and 23, respectively. These articles aim at providing vulnerable parties an opportunity to reach a choice of court agreement, while offering protection against the abuses of stronger parties. In this view Art. 25 is the most important for the new international commercial courts. For more on Art. 25 see: U. Magnus, ‘Introduction to Articles 25-26’, in U. Magnus and P. Mankowski (eds.), European Commentaries on Private International Law: Brussels Ibis Regulation (2016) 583, at 583-669; F. Garcimartin, ‘Choice-of-Court Agreements’, in A. Dickinson and E. Lein (eds.), The Brussels I Regulation Recast (2015) 277, at 277-306.

-

5 X.E. Kramer, E. Themeli, ‘The Party Autonomy Paradigm: European and Global Developments on Choice of Forum’, in V. Lazić and S. Stuij (eds.), The Brussels Ibis Regulation: Changes and Challenges of the Renewed Procedural Scheme (2017) 27, at 38-40.

-

6 Choice habits are important because once established, it is hard to change them. Certain game theories explain that if for some reason a choice option attracts the more attention, that is, is the most chosen, most players develop their strategies assuming that all the others will choose that option. At that point the expectation becomes self-fulfilling, and the option that has a starting edge draws even more attention towards itself. See also: T. Ginsburg, R.H. McAdams, ‘Adjudicating in Anarchy: An Expressive Theory of International Dispute Resolution’, 45 William and Mary Law Review 1229, at 1264-1266, and 1256 (2004). Some choice habits take the form of default contractual terms, and at that point become ‘sticky’. See for more: D. Snyder, ‘Private Lawmaking’, 64 Ohio State Law Journal 371, at 417 (2003).

-

7 Choice overload affects lawyers as well. However, when it comes to making a legal choice, lawyers’ choice overload limit may be higher than that of their clients. On the psychology of legal choice making see: G. Low, ‘A Psychology of Choice of Laws’, 24 European Business Law Review 363 (2013); G. Cuniberti, ‘The International Market for Contracts: The Most Attractive Contract Laws’, 34 Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business 455 (2014).

-

8 For a psychological perspective see: R. Salecl, ‘Society of Choice’, 20 A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 157 (2009); B. Schwartz, ‘The Tyranny of Choice’, 290 Scientific American 70 (2004); B. Schwartz, A. Ward, J. Monterosso, S. Lyubomirsky, K. White & D.R. Lehman, ‘Maximizing Versus Satisficing: Happiness Is a Matter of Choice’, 83 Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1178 (2002).

-

9 Lack of information can be considered also a practical hurdle.

-

10 Here I mean both lawyers hired as external experts, or as internal employees of legal entities. The presence of a lawyer in the structure of the legal entity may help to overcome some of these psychological problems. But considering the complicated source of these problems and the nature of the legal reasoning, these lawyers are not enough to overcome all of these psychological hurdles.

-

11 D.M. Engel, ‘Society of Choice’, 2 American Bar Foundation Research Journal 817, at 820-1 (1977).

-

12 R. van den Bergh and Y. Montangie, ‘Competition in Professional Services Markets: Are Latin Notaries Different?’, 2 Journal of Competition Law and Economics 189, at 193 (2006); U. Dulleck and R. Kerschbamer, ‘On Doctors, Mechanics, and Computer Specialists: The Economics of Credence Goods’, 44 Journal of Economic Literature 5 (2006).

-

13 It can be questioned at this point whether or not companies with an internal lawyer or legal department can overcome this situation. The answer is yes and no: yes, in case the lawyer is knowledgeable enough and the case is part of this knowledge; no, if the case is complicated and if the lawyer lacks the necessary knowledge. It should be taken into account that lawyers tend to specialise in particular fields of law; and while experts on their field, they may not be able to give an opinion in others fields. But regardless of the position, the lawyer remains the most important element in the choice of court process.

-

14 G.K. Hadfield, ‘The Price of Law: How the Market for Lawyers Distorts the Justice System’, 98 Michigan Law Review 953, at 972-6 (2000).

-

15 It helps in this regards the fact that lawyers are highly specialised and clustered in small speciality groups. See for this J.P. Heinz, E.O. Laumann, R.L. Nelson & E. Michelson, ‘The Changing Character of Lawyers’ Work: Chicago in 1975 and 1995’, 32 Law and Society Review 751, (2006).

-

16 L.E. Ribstein, ‘Lawyers as Lawmakers: A Theory of Lawyer Licensing’, 69 Missouri Law Review 299, at 314-5 (2004).

-

17 L.G. Moser Meira, ‘Parties’ Preferences in International Sales Contracts: An Empirical Analysis of the Choice of Law’, 20 Uniform Law Review 19 (2015); T. Eisenberg and G. Miller, ‘The Flight to New York: An Empirical Study of Choice of Law and Choice of Forum Clauses in Publicly-Held Companies’ Contracts’, 30 Cardozo Law Review 1475 (2008-2009); G. Cunibertit, ‘The Laws of Asian International Business Transactions’, 25 Washington International Law Journal 35 (2016); G. Cunibertit, ‘The International Market for Contracts: The Most Attractive Contract Laws’, 34 Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business 455 (2014); S. Vogenauer, ‘Regulatory Competition through Choice of Contract Law and Choice of Forum in Europe: Theory and Evidence’, European Review of Private Law 13 (2013); S. Sanga, ‘Choice of Law: An Empirical Analysis’, 11 Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 894 (2014).

-

18 Among the surveys organised on lawyers: P. Durand-Barthez, ‘The “Governing Law” Clause: Legal and Economic Consequences of the Choice of Law in International Contracts’, International Business Law Journal 505 (2012).

-

19 As mentioned, the survey was conducted in the ambit of a previous study. See n. 3.

-

20 The American Lawyer, October 2014.

-

21 The Lawyer, periodically, publishes the European 100 Report, which is an analysis of the market for lawyers in the EU and focusing only on the continental law firms. For this survey, I used data from the 2014 Report. See for the updated version: https://www.thelawyer.com/reports/european-100-2018-report/ (last visited 8 February 2019).

-

22 Compared to Junior Associates with 7.3 per cent, and Associates with 16.7 per cent.

-

23 These results are comparable with the results of the Vogenauer (see n. 17) and the Lein surveys (see n. 2), thought the target population is different.

-

24 For this, consider also the surveys of Durnad-Barthez, and Vogenauer. Above n. 17 and 18.

-

25 In the EU, England ranks seventh after Netherlands, Denmark, Germany, Sweden, Finland, Austria, and Estonia. RLI data can be accessed at http://data.worldjusticeproject.org/#table (last visited 8 February 2019).

-

26 See n. 3, at 245.

-

27 Already, the research of Lein was suggesting this for a different group of respondents. See Lein n. 2.

-

28 Foreword to the 2018 EU Justice Scoreboard.

-

29 Relative because it is difficult to find a reference frame in which to assess the importance of the data. In absence of any reference frame, data from different Member States can be compared with each other to consider the relative health of each Member State in relation with the others.

-

30 These sub-factors are ‘Accessibility and affordability’, ‘No discrimination’, ‘No corruption’, ‘No improper government influence’, ‘No unreasonable delay’, ‘Effective enforcement’, and ‘Impartial and effective ADRs’.

-

31 European Free Trade Association includes Iceland, Lichtenstein, Norway, and Switzerland.

-

32 The bill can be accessed at the official page of the Belgian parliament: http://www.dekamer.be/doc/flwb/pdf/54/3072/54k3072011.pdf (last visited 8 February 2019).

-

33 This is also accepted in the bill. In particular see page 10-11.

-

34 Selecting the best judges to sit in the courts and supporting them with lay judges with a high reputation in field may be very productive according to Coyle. This is often mentioned as a success factor for arbitration. J.F. Coyle, ‘Business Courts and Interstate Competition’, 53 William and Mary Law Review 1915, at 1972-1973 (2012).

-

35 Law Made in Germany is a brochure prepared and published by a consortium of German institutions, which promote the German legal culture including law and courts. It is also served by a dedicated website: https://www.lawmadeingermany.de/ (last visited 8 February 2019).

-

36 For instance better resources, better trained lawyers, more human resources in courts, etc.

-

37 In 2010, the courts of Cologne, Bonn, and Aachen created a project to use English as the language of oral proceedings in case parties would ask for it. The attempt was not very successful because apart from the oral part, the rest of the process was in German. https://www.lto.de/recht/hintergruende/h/modellprojekt-in-nrw-lg-koeln-goes-international/ (last visited 8 February 2019).

-

38 “Gerichtsverfassungsgesetz in der Fassung der Bekanntmachung vom 9. Mai 1975 (BGBl. I S. 1077), das zuletzt durch Artikel 1 des Gesetzes vom 12. Juli 2018 (BGBl. I S. 1151) geändert worden ist”.

-

39 Deutscher Bundestag, Entwurf eines Gesetzes zur Einführung von Kammern für Internationale Handelssachen (KfiHG), Drucksache 19/1717 of 18 April 2018, Begründung, at 8-10 available at http://dipbt.bundestag.de/dip21/btd/19/017/1901717.pdf (last visited 8 February 2019).

-

40 http://conflictoflaws.net/2017/the-justice-initiative-frankfurt-am-main-2017-law-made-in-frankfurt/ (last visited 8 February 2019).

-

41 https://ordentliche-gerichtsbarkeit.hessen.de/ordentliche-gerichte/lgb-frankfurt-am-main/lg-frankfurt-am-main/chamber-international (last visited 8 February 2019).

-

42 Judges concentration is similar to what was already mentioned in n. 30 above.

-

43 The protocol that establishes this chamber: https://www.cours-appel.justice.fr/sites/default/files/2018-06/CICAP_English_Protocole%20barreau%20de%20Paris%20-%20Cour%20d’appel%20de%20Paris_mai2018.pdf (last visited 8 February 2019).

-

44 The protocol: https://www.cours-appel.justice.fr/sites/default/files/2018-06/CICAP_EnglishVersion_Protocole%20barreau%20de%20Paris%20-%20Tribunal%20de%20commerce%20de%20Paris.pdf (last visited 8 February 2019).

-

45 See the article from Biard in the same issue of this journal. A. Biard, ‘International Commercial Courts in France: Innovations Without Revolution?’, Erasmus Law Review (2019).

-

46 E. Jeuland, ‘The International Division of the Paris Commercial Court’, 4 Tijdschrift voor Civiele Rechtspleging 143, at 144 (2016).

-

47 Question 6 from the Survey.

-

48 G. Antonopoulou, E. Themeli and X.E. Kramer, ‘No fake news: the Netherlands Commercial Court proposal approved!’, http://conflictoflaws.net/2018/no-fake-news-the-netherlands-commercial-court-proposal-approved/ (last visited 8 February 2019).

-

49 See also the bill on the NCC ‘Reglement voor de internationale handelskamers van de rechtbank Amsterdam (NCC District Court) en het gerechtshof Amsterdam (NCC Court of Appeal)’ available at: https://www.rechtspraak.nl/SiteCollectionDocuments/concept-ncc-reglement-juni-2018.pdf (last visited 8 February 2019).

-

50 See the article from Bauw in the same issue of this journal. E. Bauw, ‘Commercial Litigation in Europe: In Transformation: The Case of the Netherlands Commercial Court’, Erasmus Law Review (2019).

-

51 Thompson Reuters®, ‘Catalyst or Catastrophe? How Brexit Will Impact Law Firms’, (2018), Thompson Reuters®, London.

-

52 White&Chase® and Queen Mary University London, ‘2018 International Arbitration Survey: The Evolution of International Arbitration’, (2018), White&Chase® and Queen Mary University London, London.

Erasmus Law Review |

|

| Article | Matchmaking International Commercial Courts and Lawyers’ Preferences in Europe |

| Trefwoorden | choice of court, commercial court, lawyers’ preferences, survey on lawyers, international court |

| Auteurs | Erlis Themeli * xThis project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 726032). Information on the ERC consolidator project ‘Building EU Civil Justice: challenges of procedural innovations – bridging access to justice’ is available at http://www.euciviljustice.eu/. |

| DOI | 10.5553/ELR.000119 |

|

Toon PDF Toon volledige grootte Samenvatting Auteursinformatie Statistiek Citeerwijze |

| Dit artikel is keer geraadpleegd. |

| Dit artikel is 0 keer gedownload. |

Erlis Themeli, "Matchmaking International Commercial Courts and Lawyers’ Preferences in Europe", Erasmus Law Review, 1, (2019):70-81

|

France, Germany, Belgium, and the Netherlands have taken concrete steps to design and develop international commercial courts. Most of the projects claim to be building courts that match the preferences of court users. They also try to challenge England and Wales, which evidence suggests is the most attractive jurisdiction in the EU. For the success of these projects, it is important that their proposed courts corresponds with the expectations of the parties, but also manages to attract some of the litigants that go to London. This article argues that lawyers are the most important group of choice makers, and that their preferences are not sufficiently matched by the new courts. Lawyers have certain litigation service and court perception preferences. And while the new courts improve their litigation service, they do not sufficiently addressed these court perception preferences. |