-

1 Introduction

Businesses, including multinational enterprises, are expected to contribute positively to societies, meaning that their minimum responsibility entails to ‘do no harm’.1x A. Warhurst, ‘Future Roles of Business in Society: The Expanding Boundaries of Corporate Responsibility and a Compelling Case for Partnership’, 37 Futures 151, at 152 (2005). However, multinational enterprises do not always live up to this expectation and at times do not meet the basic responsibility to ‘do no harm’.2x https://nos.nl/nieuwsuur/artikel/2022507-nederlands-farmaciebedrijf-levert-executie-medicijn.html (last visited 9 January 2022).,3x www.nporadio1.nl/onderzoek/2253-zo-is-de-nederlandse-overheid-betrokken-bij-milieuschade-in-brazilie (last visited 9 January 2022).,4x www.rtlnieuws.nl/geld-en-werk/artikel/1800936/milieudefensie-oeso-klacht-tegen-rabobank (last visited 9 January 2022). In other words, there is room for improvement in terms of responsible business conduct (RBC) by multinational enterprises. RBC implies that multinational enterprises are expected to comply with international standards in meeting their responsibility to ‘do no harm’ in societies where they conduct business. In order to encourage multinational enterprises to develop proper RBC, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has developed the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (OECD Guidelines).5x OECD, OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises 2011 (2011). The OECD Guidelines consist of legally non-binding standards of RBC for multinational enterprises. This instrument is prominent among similar instruments because of its implementation mechanism, the National Contact Point (NCP) and the NCP specific instance procedure (NCP procedure).6x J.C. Ochoa Sanchez, ‘The Roles and Powers of the OECD National Contact Points Regarding Complaints on an Alleged Breach of the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises by a Transnational Corporation’, 84 Nordic Journal of International Law 89, at 90-94 (2015). While the Procedural Guidance which is attached to the OECD Guidelines sets out the NCP procedure in some detail, NCPs enjoy discretion as to whether they monitor the implementation of the agreements and recommendations provided at the end of the mediation phase of the procedure.7x The Procedural Guidance is part of the Amendment of the Decision of the Council on the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. OECD, Procedural Guidance and Commentary on the Implementation Procedures of the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises in OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises 2011 (2011), at 85. Whether and how the Dutch NCP uses this discretion to secure RBC improvement by multinational enterprises is the focus of this article.

The NCP is a state-based non-judicial grievance mechanism.8x United Nations, Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (2011), at 27-28. Each state that has adhered to the OECD Guidelines has the duty to establish and facilitate an NCP.9x OECD, above n. 5, at 3. In order to further the effectiveness of the OECD Guidelines,10x OECD, above n. 7, at 71. NCPs are expected to contribute towards resolving issues addressed in specific instances by way of the NCP procedure.11x Ibid., at 72-73. The term ‘specific instances’ refers to a particular situation in which, based on a complaint, it is suspected that a multinational enterprise has not observed the OECD Guidelines. Stakeholders, such as non-governmental organisations (NGOs), can submit a complaint about the alleged non-observance of the OECD Guidelines to an NCP, which then proceeds to assess the complaint.12x Ibid.

In order to provide guidance to the NCPs on how to execute the NCP procedure, the Procedural Guidance sets out steps that are expected to be taken during the procedure.13x OECD, above n. 7, at 71-75. The first step involves the NCP deciding whether it will assist the parties involved in resolving the issue addressed in a complaint.14x Ibid., at 81-87. If the NCP decides to assist the parties, it will use mediation to help resolve the issues raised in the complaint.15x Ibid. The result of this second step in the procedure is ideally a set of agreements reached by the parties as well as recommendations that the NCP adopts. If considered appropriate, the NCP may execute a third step to follow-up (follow-up step) on the implementation of the agreements and recommendations, written up in a follow-up statement.16x Ibid., at 85. However, this follow-up step is not compulsory, and detailed instructions on the execution of this step are not provided in the Procedural Guidance. As a result, an NCP has discretion in deciding whether, and to what extent, it will engage in the follow-up step.

According to the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGP), monitoring the implementation of outcomes is key to ensure the effectiveness of a non-judicial grievance mechanism procedure.17x United Nations, above n. 8, at 33. Also, OECD Watch has addressed the importance of monitoring during the NCP procedure to ensure long-term impact.18x OECD Watch, Remedy Remains Rare: An Analysis of 15 Years of NCP Cases and their Contribution to Improve Access to Remedy for Victims of Corporate Misconduct (2015), at 47. Furthermore, it often remains unclear what changes a company has introduced to follow-up on the agreements and recommendations that emerged as a result of the mediation phase.19x J. Ruggie and T. Nelson, ‘Human Rights and the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises: Normative Innovations and Implementation Challenges’, Corporate Social Responsibility Initiative Working Paper 66, at 20 (2015). Therefore, the focus of this article is on the role of monitoring in the realisation of RBC improvement by multinational enterprises during the NCP procedure.

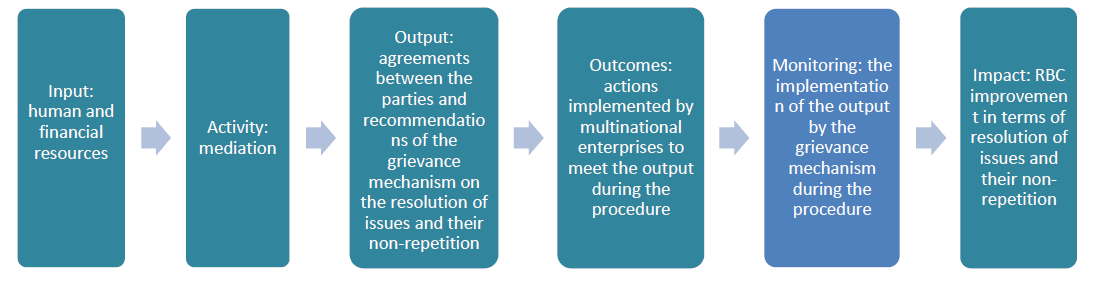

Since the Procedural Guidance does not outline how the follow-up step is to be executed, an analytical framework based on Clark et al. (2004)20x C. Clark, W. Rosenzweig, D. Long & S. Olsen, ‘Double Bottom Line Project Report: Assessing Social Impact in Double Bottom Line Ventures’, Methods Catalog Columbia Business School, at 14 (2004). and the UNGP has been developed to assess whether and how the Dutch NCP engages in follow-up to monitor the implementation of agreements and recommendations. To provide insights on the results achieved during the follow-up step, the elements output, outcome and impact of the framework developed by Clark et al. (2004) have been used in the analytical framework for the follow-up step. This framework has been further advanced by adding expectations from the UNGP regarding mechanisms such as the NCP. The UNGP focus on the duty of states to protect human rights, the responsibility of business enterprises to respect human rights, and access to remedy.21x United Nations, above n. 8. The UNGP is reflected in the OECD Guidelines’ chapter on human rights. Also, they pay specific attention to expectations from state-based non-judicial grievance mechanisms, for example, in terms of monitoring the implementation of outcomes during the procedure of the mechanism. The NCP is one such mechanism. Hence, the elements output, outcomes, monitoring, and impact are used in the framework developed for the analysis of the follow-up step.

This framework is used in this article for the analysis of the follow-up statements issued by the Dutch NCP. The Dutch NCP was chosen for this research because it has a best practice organisational structure,22x OECD, Guide for National Contact Points on Structures and Activities, OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (2019), at 11-12. which is further explained later. The question this study seeks to answer is ‘does the Dutch NCP use its discretion to engage in the follow-up step to monitor, and therefore to secure RBC improvement by multinational enterprises?’

The research for this article was conducted as follows. A literature review was carried out to develop insights into the OECD Guidelines and the role of the NCPs. The analytical framework used in this research was developed for the follow-up step based on the framework that Clark et al. (2004) advanced and the standards that the UNGP set for a state-based non-judicial grievance mechanism. All eight follow-up statements published between 2011 and 2021 and other relevant information available on the website of the Dutch NCP were analysed to assess the Dutch NCP procedure. The analysis demonstrates the functioning of a procedure that seeks to secure the implementation of a non-binding international regulatory instrument and whether the procedure as currently exercised is fit for its purpose. This research thereby contributes to the debate about the contribution of state-based non-judicial grievance mechanisms to RBC improvement by multinational enterprises.

This article is structured as follows. First, the relevant provisions of the OECD Guidelines and how the NCPs operate are presented. Next, the framework for analysis of the follow-up step is outlined and constructed. Thereafter, this framework is used to analyse whether and how the Dutch NCP engages in monitoring the implementation of the agreements and recommendations issued at the end of the second step of eight different NCP procedures. Finally, conclusions are drafted and suggestions for further research are provided. -

2 The OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises

Multinational enterprises conduct business on a global level, and consequently, how they conduct their business affects many societies around the world. To mitigate negative effects and increase positive effects, international organisations, such as the International Labour Organization (ILO), the United Nations (UN) and the OECD, have developed international instruments that provide standards for RBC and their implementation.23x K. Buhmann, ‘Public Regulators and CSR: The “Social Licence to Operate” in Recent United Nations Instruments on Business and Human Rights and the Juridification of CSR’, 136 Journal of Business Ethics 699, at 709-711 (2016). Examples of relevant instruments are the ILO’s Tripartite declaration of principles concerning multinational enterprises and social policy, the UNGP and the OECD Guidelines.24x A. Kun, ‘How to Operationalize Open Norms in Hard and Soft Laws: Reflections Based on Two Distinct Regulatory Examples’, 34 International Journal of Comparative Labour Law and Industrial Relations 23, at 24 (2018). These legally non-binding instruments set standards for RBC and aim to improve the social responsibility of multinational enterprises, irrespective of their location or contractual arrangements.25x J. Southalan, ‘Human Rights and Business Lawyers: The 2011 Watershed’, 90 Australian Law Journal 889, at 896 (2016).

Within the field of international instruments for RBC, the OECD Guidelines are considered a relevant present-day set of global RBC standards.26x K. da Costa, ‘Corporate Accountability in the Samarco Chemical Sludge Disaster’, 26 Disaster Prevention and Management 540, at 546 (2017).,27x Kun, above n. 24, at 41. The OECD Guidelines ‘concern those adverse impacts that are either caused, or contributed to, by the enterprise, or are directly linked to their operations, products or services by a business relationship’.28x OECD, above n. 5, at 23. Multinational enterprises are expected by the OECD Guidelines to take responsibility in terms of identifying, preventing and mitigating negative impacts associated with their business activities.29x Kun, above n. 24, at 41. Also, multinational enterprises are expected to redress these adverse impacts if they occur.30x Ibid.

The first version of the OECD Guidelines was adopted as part of the Declaration on International Investment and Multinational Enterprises by the OECD Ministerial Council in 1976.31x A. Marx and J. Wouters, ‘Rule Intermediaries in Global Labor Governance’, 670 The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 189, at 192 (2017). The aim of the OECD Guidelines remains to encourage positive contributions by multinational enterprises to economic, environmental and social goals.32x Ibid., at 192. In addition, this instrument seeks to encourage companies to take positive actions, as well as to avoid negative impacts on the societies wherein they operate.33x da Costa, above n. 26, at 547.

The 2011 version is the latest update of the OECD Guidelines, which was developed and adopted by governments, and it applies to multinational enterprises and their business activities in home and host states.34x D. Carolei, ‘Survival International v World Wide Fund for Nature: Using the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises as a Means of Ensuring NGO Accountability’, 18 Human Rights Law Review 371, at 373 (2018). The 38 OECD member states and 12 non-OECD member states have adopted the OECD Guidelines.35x www.oecd.org/investment/mne/oecddeclarationanddecisions.htm (last visited 15 April 2022), the OECD member states are: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States. The non-OECD member states that have adopted the OECD Guidelines are Argentina, Brazil, Croatia, Egypt, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Morocco, Peru, Romania, Tunisia, Ukraine and Uruguay. It is comprised of human rights, labour standards including employment and industrial relations, environmental standards, and standards related to bribery, disclosure and transparency, consumer interests, science and technology, competition and taxation.36x Buhmann, above n. 23, at 702. The 2011 OECD Guidelines introduced a new chapter on human rights which is consistent with the UNGP.37x OECD, above n. 5, at 3. Also, the latest version expects the business community to take responsibility in terms of their supply and value chains.38x da Costa, above n. 26, at 547. This means that potential supply chain risks should be included in the due diligence process of businesses. Moreover, the OECD Guidelines are unique in that they come with an implementation mechanism, namely, the NCP procedure.39x Ochoa Sanchez, above n. 6, at 90-92.2.1 National Contact Points

States that have adopted the OECD Guidelines are required to establish an NCP in order to promote and implement the OECD Guidelines,40x K. Buhmann, ‘Analysing OECD National Contact Point Statements for Guidance on Human Rights Due Diligence: Method, Findings and Outlook’, 36 Nordic Journal of Human Rights 390, at 391 (2018).,41x OECD, above n. 5, at 3. and they are responsible for facilitating public awareness and understanding of how the NCP system works.42x OECD, above n. 7, at 71-73. Also, such states are responsible for supporting the NCPs in terms of financial and human resources.43x Ibid., at 77.

NCPs can have different institutional structures; they can consist of government officials, independent experts, business community representatives, labour organisations and NGOs.44x Ibid., at 71. For example, the Dutch NCP consists of four independent members, supported by a secretariat consisting of four government officials from different ministries.45x www.oecdguidelines.nl/ncp/ncp-members (last visited 9 January 2022). This NCP is hosted by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the Minister for Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation is politically responsible for the functioning of the Dutch NCP.46x www.oecdguidelines.nl/ncp/documents/publication/2014/07/01/ncp-establishment-order-2014 (last visited 9 January 2022). Furthermore, the Dutch NCP has an independent organisational structure, and it is responsible for its own procedures and decision-making.47x www.oecdguidelines.nl/ncp (last visited 9 January 2022).

To furthermore ensure the effectiveness of the OECD Guidelines, each NCP has two tasks.48x OECD, above n. 7, at 71-73. Firstly, the NCP must promote the OECD Guidelines by creating awareness about the instrument.49x Carolei, above n. 34, at 373. Amongst others, this involves distributing information about the OECD Guidelines and the NCP procedure and responding to questions regarding the OECD Guidelines.50x K.A. Reinert, O.T. Reinert & G. Debebe, ‘The New OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises: Better but Not Enough’, 26 Development in Practice 816, at 819 (2016). As such, the NCP has a preventative and a proactive role.51x Buhmann, above n. 40, at 391.

Secondly, the NCP must contribute to resolving issues addressed in complaints on specific instances by way of the NCP procedure.52x OECD, above n. 7, at 72-73. This implies that in addition to a preventative and a proactive role, the NCP has a reactive and a remedial role,53x Buhmann, above n. 40, at 391. in which it mediates between involved parties on issues raised about alleged non-observance of the OECD Guidelines.54x Carolei, above n. 34, at 373. In general, a complaint must be addressed to the NCP of the country in which the specific instance occurred.55x OECD, above n. 7, at 82. For example, if a specific instance regarding a business activity of a Dutch multinational enterprise took place either in the Netherlands or in a non-adhering state to the OECD Guidelines, then the complaint can be addressed to the Dutch NCP. In case the specific instance took place in a country which adheres to the OECD Guidelines, and where an NCP is already based, then the complaint can be addressed to the NCP of that state. However, there have been exceptions in the past, for example, in terms of procedures in which several NCPs worked together and several multinational enterprises were involved.56x OECD, Coordination between OECD National Contact Points during Specific Instance handling (2019), at 7. Furthermore, even though the OECD Guidelines are primarily directed at multinational enterprises, there have been cases in which state-based enterprises, small-medium enterprises or governments were involved in NCP procedures. Nonetheless, these procedures are not discussed in depth since the focus in this article is not on exceptional procedures. The focus in this article is more general and rather on monitoring of mediations results during the end phase of Dutch NCP procedures.

In general, the Dutch NCP has been praised for its independent organisational structure57x S. van ‘t Foort, ‘Due Diligence and Supply Chain Responsibilities in Specific Instances’, 4 Erasmus Law Review 61, at 64 (2019). and for its approach during the NCP procedure.58x S. van ‘t Foort, T. Lambooy & A. Argyrou, ‘The Effectiveness of the Dutch National Contact Point’s Specific Instance Procedure in the Context of the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises’, 16 McGill Journal of Sustainable Development Law 194, at 201-5 (2020). For example, from 2012 until 2019, the Dutch NCP performed better than other NCPs in terms of numbers in agreements reached between the parties involved.59x van ‘t Foort, above n. 58, at 228. However, the increased numbers of complaints addressed to the Dutch NCP in recent years have been a burden on its human and financial resources.60x Ibid., at 229-30. This phenomenon may raise the need for further resources at the Dutch NCP to more effectively tackle all the cases. -

3 The NCP Procedure and Framework on the Follow-Up Step

States that have adopted the OECD Guidelines are expected to use the Procedural Guidance to organise the structure of their NCP and for the implementation of the NCP procedure. The Dutch government, as many others, has based the Dutch NCP procedure on the Procedural Guidance.61x https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0035293/2014-12-20 (last visited 9 January 2022). OECD, above n. 7, at 71-87. However, the Procedural Guidance provides room for discretion when implementing the NCP procedure. For example, the Procedural Guidance addresses that when deemed appropriate by the NCP, it can follow-up on the results of the mediation phase.62x OECD, above n. 7, at 85. In other words, the NCP has discretionary room for determining how it implements the NCP procedure. This section develops an analytical framework that will be used as a tool to assess whether and how the NCP in the Netherlands uses this discretion to assure RBC improvement by multinational enterprises.

The Procedural Guidance outlines the first and second steps that are to be taken during the NCP procedure. The third step, however, is not outlined: it is up to the NCP to decide how to proceed further. Hence, the NCP enjoys full discretion after the completion of the second step.

As mentioned before, during the first step of initial assessment, the NCP decides whether it will assist the parties involved in resolving the issue addressed in a specific instance, based on whether it is relevant to the implementation of the OECD Guidelines.63x Ibid., at 81-87. The NCP is expected to make this decision publicly available in a published statement.64x Ibid. In case the NCP decides to assist the parties involved, mediation takes place during the second step.65x Ibid. Thereafter, the NCP is expected to publish a final statement containing its own recommendations and any agreements reached between the parties involved.66x Ibid. In this statement, the NCP is expected to describe the issues addressed and the steps that are to be taken during the NCP procedure.67x Ibid., at 73. The NCPs are also expected to issue a statement in the case where no agreement was reached or when the complainant or the multinational enterprise is unwilling to participate in the NCP procedure.68x Ibid. In this case, the statement also has to describe the issue addressed, the reasons for the decision and the procedure initiated by the NCP in assisting the parties.69x Ibid. Additionally, the NCP can provide recommendations on the implementation of the OECD Guidelines, and it can address the reasons why agreement could not be reached.70x Ibid. NCPs are expected to provide the parties involved in a specific instance procedure with the opportunity to comment on the statements before publication.71x Ibid. However, it is for NCPs to decide whether to include any changes that either party might suggest in the statements.72x Ibid., at 85.

If considered appropriate, the NCP can decide to follow-up on the implementation of its recommendations and the agreements reached.73x Ibid. This third step, the follow-up step, comes after the completion of the final statement. In cases where the NCP conducts this step, it is expected to address the time frame for this step in the final statement.74x Ibid. During the follow-up step, the multinational enterprise has the opportunity to work on the implementation of recommendations and agreements. At the end of the given time frame, a statement about the results of the steps taken by the multinational enterprise is made public.75x Ibid. The follow-up step focusses on the results of mediation, and, therefore, it is a significant step in the NCP procedure in terms of assuring the broader aim of the OECD Guidelines, which is RBC improvement by multinational enterprises.3.1 Framework on the Follow-Up Step

Since the follow-up step seems to be crucial in achieving RBC improvement, the analytical framework for the follow-up step based on a framework developed by Clark et al. (2004) and the UNGP has been developed later. The Clark et al. (2004) framework has been used to provide clarity on the practice of the NCP procedure. The UNGP has been used to include expectations in terms of monitoring the implementation of outcomes during the NCP procedure. Monitoring in this article means that the NCP actively oversees and ensures the implementation of the results of mediation during the NCP procedure.

Elements of Clark et al. (2004) and the expectations from the UNGP have been brought together in the framework for the follow-up step to analyse, and thereby provide clarity regarding the achieved accomplishments of the Dutch NCP procedure in terms of improved RBC of the involved multinational enterprises. The proposed framework is outlined later.

The framework developed by Clark et al. (2004) identifies the input, output, outcomes and impact of an activity.76x Clark, above n. 20, at 14. An activity may be a project, programme, procedure or an intervention. Such an activity can result in actions that are to be taken during the activity. These actions can produce impacts, and impact is the most significant result of a particular action.77x Ibid. In other words, the highest order of effect of an activity is impact that is generated by the implementation of different actions to achieve the overall goal for which the activity is organised. Outcomes can consist of specific changes in knowledge or gaining skills because of the implemented actions during an activity.78x Ibid. Output consists of the directly measurable results of an activity, such as the sum of agreements on an organisation’s operation that are expected to be implemented in actions during the activity.79x Ibid., at 14. Input consists of resources for an activity, such as human and financial resources.80x Ibid.

Since the Procedural Guidance in the OECD Guidelines does not provide details on how the follow-up step is to be performed and what the results of this step should be, the UNGP has been used for the further development of the analytical framework. The UNGP-framework is used in this research because it is an authoritative framework that formulates expectations of a state-based non-judicial grievance mechanism, such as the NCP. The authority of the UNGP is shown by the fact that it has been used for developing the human rights chapter in the 2011 OECD Guidelines. This human rights chapter is the most referenced chapter in complaints to NCPs, and most of the NCP procedures have dealt with cases related to this chapter.81x https://mneguidelines.oecd.org/Flyer-OECD-National-Contact-Points.pdf (last visited 9 January 2022).Framework for a state-based non-judicial grievance mechanism

According to the UNGP, states should investigate and redress business-related human rights abuses,82x United Nations, above n. 8, at 27. by providing effective state-based non-judicial grievance mechanisms.83x Ibid., at 33. This term indicates a process in which grievances on business-related human rights abuse can be addressed.84x Ibid., at 27. These grievance mechanisms can be administered for example by a branch or agency of the state, or by an independent body on a statutory or constitutional basis.85x Ibid. Examples of such mechanisms are NCPs, ombudsperson offices and complaints offices run by governments.86x Ibid., at 28. The broader aim of state-based non-judicial grievance mechanisms can be interpreted as achieving an impact in terms of RBC improvement, for example, by businesses such as multinational enterprises.

To achieve impact in terms of RBC improvement by multinational enterprises, the focus of a state-based non-judicial grievance mechanism should be on the resolution of addressed issues on business misconduct and on preventing these issues from recurring in the future.87x Ibid., at 33-35.

Outcomes needed for achieving such impact are actions executed by multinational enterprises on resolving identified issues and preventing their occurrence in the future through guaranteeing non-repetition.88x Ibid., at 27. For example, by committing to approaches that solve the identified issue and prevent misconduct from recurring and by including RBC improvement in current and new business activities of multinational enterprises. According to the UNGP, a state-based non-judicial grievance mechanism should provide clarity on the procedure, outcomes and monitoring of the implementation of the results.89x Ibid., at 33-35. Thus, monitoring the implementation of mediations’ results should take place during these procedures to ensure RBC improvement by multinational enterprises. Therefore, monitoring plays a key role during the procedure of a state-based non-judicial grievance mechanism.

Outputs, which are the results of the mediation phase, are necessary towards achieving RBC improvements. These are recommendations provided by the state-based non-judicial grievance mechanism and agreements between the involved parties on the resolution and prevention of business misconduct. These recommendations and agreements can be addressed during a mediation activity with the involved parties.90x Ibid., at 30. According to the UNGP, states are expected to provide inputs for these mechanisms, such as support and resources in terms of funding and expertise.91x Ibid., at 28.

Figure 1 provides an overview of the interpretation of the UNGP for the input, output, outcomes, monitoring and impact of mediation during a state-based non-judicial grievance mechanism procedure.

Based upon the context of the NCP procedure and the UNGP, ‘impact’ refers to RBC improvement by multinational enterprises in terms of the resolution of issues addressed in specific instances and their non-repetition. To achieve this impact, outcomes in the NCP procedure should consist of the implementation of actions by multinational enterprises to meet the recommendations and agreements on the identified issue. Actions may consist of improved supply chain policies, improvement in investment policies, implementation of systematic approaches that actively prevent misconduct or approaches that involve RBC improvement in subsequent business activities of the multinational enterprises in question. To assure the completion of the agreements and recommendations, the discretion for the follow-up step should be used to monitor the implementation of actions during this step. This means that the follow-up step should only end when all necessary actions have been implemented by the multinational enterprise. Information on this implementation, monitoring and completion should be addressed in the follow-up statement. As such, the results of the NCP procedure and its impact in terms of RBC improvement can be clarified.

Outputs of mediation during the NCP procedure should address the non-repetition of issues, because it is important to prevent the issue from recurring in the future, as mentioned in the UNGP. Thus, besides resolving the identified issues, the NCP should also focus on preventing multinational enterprises from making the same mistakes in the future.Table 1 Framework for the follow-up step in the NCP procedureOutput: agreements between the parties and recommendations of the NCP on the resolution of issues and their non-repetition Outcomes: actions implemented by multinational enterprises to meet the output during the follow-up step Monitoring: the implementation of the output by the NCP during the follow-up step Impact: RBC improvement in terms of resolution of issues and their non-repetition Multinational enterprises Categories of output + = all outputs have been implemented

+/− = some outputs have been implemented

− = no outputs have been implemented+ = the NCP has used the discretion to monitor the implementation of the outputs

− = the NCP has not used the discretion to monitor the implementation of the outputs+ = RBC improvement was clearly achieved

+/− = RBC improvement was achieved to some extent

− = RBC improvement has not been achievedFor example, outputs that aim for improved policies and procedures regarding supply chains, stakeholder engagement with societies, transparency of investment strategies and grievance mechanisms that provide stakeholders with the opportunity to address their concerns about business activities.

Within the context of the NCP procedure, the activity is mediation in which the NCP, the complainant and the multinational enterprise are involved. Input for this activity consists of financial and human resources provided to the NCP by its national government.

However, the NCP procedure should not only focus on its outputs but also on its impact, that is, RBC improvement. Hereby, the follow-up step plays a significant role, as the discretion for this step provides the opportunity to focus on the implementation and monitoring of outputs to achieve RBC improvement by multinational enterprises. Therefore, the proposed framework as outlined later concerns the assessment of this step in the NCP procedure.

For the assessment of the follow-up step, input and activity are less relevant, so these two elements have been excluded from the framework. The framework provides an overview of the output, outcomes, monitoring and impact of the relevant elements. Furthermore, the multinational enterprises and the categories concerning output are addressed. The outcomes have been divided according to whether implementation of the actions for all outputs has taken place, whether it has taken place in some cases and whether it has taken place at all. The focus here is on whether the actions have been completed to meet the agreements and recommendations before the end of the NCP procedure. Then, the question of whether the NCP has used its discretion to monitor the implementation during the follow-up step is addressed. This monitoring concerns assessment by the NCP during the follow-up step on the implementation of the actions by the multinational enterprise. The right-hand column addresses the question of whether RBC improvement has been clearly achieved based on the extent to which the necessary actions have been implemented. -

4 The Analysis of the Follow-Up Step in the Dutch NCP Procedure

The framework for analysis as outlined in Table 1 has been used to analyse the statements of eight Dutch NCP procedures executed between 2011 and 2021. For each of these procedures, a follow-up step was executed, and a follow-up statement was published by the Dutch NCP. Data from these statements has been used as input for Table 2. The analysis concerns the following procedures. The Mylan case on preventing the use of its products in lethal injections,92x Dutch NCP, Bart Stapert, attorney v. Mylan (2016). the Atradius Dutch State Business (ADSB) case on projects covered by export credit insurance,93x Dutch NCP, Both END et al. v. Atradius Dutch State Business (2016). the Rabobank case on financing in the palm oil sector,94x Dutch NCP, Friends of the Earth / Milieudefensie v. Rabobank (2016). the Nuon case on engagement with a local community during a business project,95x Dutch NCP, Houd Friesland Mooi! v. Nuon Enerdy N.V. (2018). the ING case on financing policies concerning climate change,96x Dutch NCP, Oxfam Novib, Greenpeace Netherlands, BankTrack and Friends of the Earth Netherlands (Milieudefensie) v. ING (2019). the Heineken case on workers’ human rights,97x Dutch NCP, Former Employees of Bralima v. Bralima and Heineken (2017). the Perfeti Van Melle’s (PVM) case on child labour and workers’ rights98x Dutch NCP, IUF v. Perfeti Van Melle (2020). and the Bresser case on respecting the human rights of local communities during business activities.99x Dutch NCP, FIVAS, the Initiative to Keep Hasankeyf Alive and Hasankeyf Matters v. Bresser (2018).

The agreements and recommendations upon mediation in these procedures concern amendments to policies and procedures, transparency, stakeholder engagement and grievance mechanisms. Policies and procedures may concern new or improved approaches by a multinational enterprise regarding distribution of products, environmental and social matters, providing financing, employment matters and business activities.Table 2 The results of the follow-up steps in the Dutch NCP procedureOutput: agreements between the parties and recommendations of the NCP on the resolution of issues and their non-repetition Outcomes: actions implemented by multinational enterprises to meet the output during the follow-up step* Monitoring: the implementation of the output by the NCP during the follow-up step** Impact: RBC improvement in terms of resolution of issues and their non-repetition*** Mylan 101 Policies and procedures +/− − +/− Transparency +/− Stakeholder engagement +/− Grievance mechanism Not applicable ADSB 102 Policies and procedures +/− − +/− Transparency +/− Stakeholder engagement + Grievance mechanism − Rabobank 103 Policies and procedures + − +/− Transparency + Stakeholder engagement Not applicable Grievance mechanism − Nuon 104 Policies and procedures Not applicable − +/− Transparency + Stakeholder engagement +/− Grievance mechanism Not applicable ING 105 Policies and procedures +/− − +/− Transparency +/− Stakeholder engagement Not applicable Grievance mechanism Not applicable Heineken 106 Policies and procedures + − + Transparency Not applicable Stakeholder engagement + Grievance mechanism + Perfetti Van Melle 107 Policies and procedures + − +/− Transparency Not applicable Stakeholder engagement +/− Grievance mechanism Not applicable Bresser 108 Policies and procedures + − +/− Transparency − Stakeholder engagement + Grievance mechanism Not applicable * + = all outputs have been implemented

* +/− = some outputs have been implemented

* − = no outputs have been implemented

** + = the NCP has used its discretion to clearly monitor the implementation of all outputs

** − = the NCP has not used its discretion to clearly monitor the implementation of all outputs

*** + = RBC improvement was clearly achieved

*** +/− = RBC improvement was achieved to some extent

*** − = RBC improvement has not been achieved

101 Dutch NCP, Bart Stapert, attorney v. Mylan (2017).

102 Dutch NCP, Both ENDS et al. v. Atradius Dutch State Business (2018).

103 Dutch NCP, Friends of the Earth / Milieudefensie v. Rabobank (2018).

104 Dutch NCP, Hou Friesland Mooi! v. Nuon Energy N.V. (2020).

105 Dutch NCP, Oxfam Novib, Greenpeace, BankTrack, Milieudefensie v. ING (2020).

106 Dutch NCP, Former employees of Bralima v. Bralima and Heineken (2021).

107 Dutch NCP, IUF v. Perfetti Van Melle (2021).

108 Dutch NCP, FIVAS, the Initiative to Keep Hasankeyf Alive and Hasankeyf Matters v. Bresser (2021).Transparency can concern publishing statements on what a multinational enterprise stands for, new or improved policies and information on business activities. Stakeholder engagement may concern engagement by a multinational enterprise with actors in a sector, local communities and employees. Grievance mechanisms can be externally or internally oriented. Externally means that stakeholders from outside the multinational enterprise can address a complaint on business conduct to the grievance mechanism. Internal means that stakeholders such as employees can address a complaint to the internal grievance mechanism.

As shown in Table 2, agreements and recommendations on improvement in policies and procedures are prominent in most Dutch NCP procedures, followed by transparency and stakeholder engagement. Contrarily, the grievance mechanism has only been part of the complaints in three specific instances. Yet, according to the UNGP, grievance mechanisms can provide important feedback from those directly affected,100x United Nations, above n. 8, at 23. concerning the business activities of multinational enterprises. Transparency, stakeholder engagement and grievance mechanisms can be considered part of the relationship between a multinational enterprise and society. In other words, the subjects of the Dutch NCP procedures discussed later concern directly or indirectly the relationship between multinational enterprises and societies in where they conduct business. Furthermore, policies and procedures are needed for achieving changes in the other three categories. Therefore, they can be considered as integral parts of agreements and recommendations during mediation.

The outcomes have been divided into categories according to the extent to which actions have been implemented to meet the agreements and recommendations in the eight follow-up steps. Not applicable means the category under output had not been part of the complaint. Monitoring has been divided into whether the Dutch NCP has used its discretion to monitor the implementation of the output during the follow-up steps. The right-hand column assesses whether RBC improvement has clearly been achieved.4.1 Analysis of the Outcomes

As discussed earlier, the implementation of actions by multinational enterprises to meet the agreements and recommendations and their monitoring by the NCP during the follow-up step are significant to achieve RBC improvement. In this section, these elements are discussed. Table 2 indicates that the actions on policies and procedures have been implemented more frequently than actions related to stakeholder engagement, transparency and grievance mechanisms. This phenomenon can be explained by the fact that, in general, new or improved policies and procedures are needed for changes in the other three areas.

Firstly, in some cases, none of the actions to meet a certain output category had been implemented during the follow-up, such as the case of ADSB and Rabobank. In these cases, none of the necessary actions were implemented to meet the agreements and recommendations made in relation to their grievance mechanisms.101x Dutch NCP, Both ENDS et al. v. Atradius Dutch State Business (2018).,102x Dutch NCP, Friends of the Earth / Milieudefensie v. Rabobank (2018). More specifically, ADSB was still in the process of improving its grievance mechanism and its publication was planned after the follow-up statement was published.103x Dutch NCP, Both ENDS et al. v. Atradius Dutch State Business (2018). Rabobank had not modified its approach to handling grievances, and it had not published a grievances procedure including a time frame; however, the bank had promised doing so during mediation.104x Dutch NCP, Friends of the Earth / Milieudefensie v. Rabobank (2018). Nonetheless, grievance mechanisms are considered significant in terms of RBC, because they can provide stakeholders with the opportunity to directly address issues related to business conduct, and this input can be used to solve and prevent repetition of these issues. Therefore, it is surprising that the NCP procedures of ADSB and Rabobank have ended without improvement of their grievance mechanisms.

Secondly, in other cases, some, but not all actions, had been implemented by the time the follow-up step was due. For instance, Bresser had not published a statement based on the OECD Guidelines regarding the risks of business conduct.105x Dutch NCP, FIVAS, the Initiative to Keep Hasankeyf Alive and Hasankeyf Matters v. Bresser (2021). Thus, in terms of transparency to stakeholders, at the end of the procedure, it was still unclear whether, and how, Bresser aimed to prevent risks related to its business conduct. Other examples are noticeable in the Mylan, ADSB and Nuon follow-up statements. These multinational enterprises have started implementing actions in terms of improvement in policies, procedures, transparency and stakeholder engagement. However, their implementation was not completed according to the follow-up statements.106x Dutch NCP, Bart Stapert, attorney v. Mylan (2017).,107x Dutch NCP, Both ENDS et al. v. Atradius Dutch State Business (2018).,108x Dutch NCP, Hou Friesland Mooi v. Nuon Energy N.V. (2020). Consequently, these Dutch NCP procedures ended without all of the outputs having been met and, therefore, with some uncertainty as to whether RBC improvement had been achieved.

Thirdly, in the cases of Bresser and Heineken, all actions to meet a certain output category had been met. For example, Bresser had implemented all actions concerning policies and procedures for its new risk management approach on human rights and stakeholder engagement.109x Dutch NCP, FIVAS, the Initiative to Keep Hasankeyf Alive and Hasankeyf Matters v. Bresser (2021). Also, Bresser had admitted that due to this approach, it withdrew from tenders that potentially involved human rights-related violations.110x Ibid. Heineken had implemented all the actions to meet all the agreements and recommendations as discussed during mediation.111x Dutch NCP, Former Employees of Bralima v. Bralima and Heineken (2021). Also, the results of the implementation in terms of RBC improvement were outlined in the follow-up statement.112x Ibid. This case illustrates that it is possible to end an NCP procedure with all outputs met and, therefore, the necessary clarity regarding RBC improvement. Furthermore, the Heineken case is still frequently referred to as a guiding example in terms of positive results achieved during an NCP procedure.113x K. Bhatt and G. Erdem Türkelli, ‘OECD National Contact Points as Sites of Effective Remedy: New Expressions of the Role and Rule of Law within Market Globalization?’ 6 Business and Human Rights Journal 423, at 445 (2021).,114x Van ‘t Foort, above n. 58, at 227.

Fourthly, monitoring of the implementation of actions had not been clearly addressed in any of the follow-up statements. This implies that the Dutch NCP had not ensured that all multinational enterprises would meet all the agreements and recommendations during the follow-up step. For example, the Dutch NCP did not monitor the progress of the negotiations on collective bargaining and right to freedom of association between the PVM BD Pvt. Ltd. Employees’ Union and PVM in Bangladesh.115x Dutch NCP, IUF v. Perfetti Van Melle (2021). Consequently, at the end of this NCP procedure, it is not known whether the addressed issue on workers’ rights has been solved by PVM. Table 2 shows that monitoring by the Dutch NCP has not taken place in any of the procedure; consequently, most of the follow-up steps have been concluded without clarity on the overall RBC improvement.

Lastly, the Dutch NCP has provided recommendations at the end of most follow-up statements. Some of these recommendations are specifically connected to the addressed issues, and others are more general. For example, the Dutch NCP recommends Mylan to write to officials in all the states who are involved in its new distribution approach.116x Dutch NCP, Bart Stapert, attorney v. Mylan (2017). This is a recommendation directly connected to the addressed issue. A more general recommendation, such as on ING’s general approach to climate issues,117x Dutch NCP, Oxfam Novib, Greenpeace, BankTrack, Milieudefensie v. ING (2020). is too broad to be met during the follow-up step. In other words, if the specific recommendations had been given before the publication of the follow-up statement, the multinational enterprises would have had the chance to meet the recommendations before the end of the NCP procedure. In this way, the NCP procedure could have been completed with more clarity on RBC improvement by the involved multinational enterprises. -

5 Conclusion

This research has raised the issue of the so-called ‘open end’ of Dutch NCP procedures, and it has provided a solution to tackle this concern, namely monitoring the implementation of results during the follow-up step. Moreover, this research has illustrated whether and how the Dutch NCP has used its discretion to secure RBC improvement by multinational enterprises during the follow-up step. To analyse the follow-up statements of Dutch NCP procedures, an analytical framework based on Clark et al. (2004) and the UNGP was used. The results of this analysis, based on the information provided in the published statements, indicate that the Dutch NCP hardly uses its discretion during follow-up steps to monitor the implementation of the output related to RBC improvement. As a result, in most procedures, RBC improvement by multinational enterprises was not clearly secured. This is evidenced by the agreements and recommendations not having been implemented by the time of the follow-up step, based on the information in the follow-up statements. Thus, the discretion that is offered by the Procedural Guidance was not sufficiently used by the Dutch NCP to monitor the implementation of all the necessary actions by multinational enterprises. Therefore, the Dutch NCP did not engage in all it could have in securing RBC improvement. Admittedly, the number of complaints addressed to the Dutch NCP has increased considerably in the recent years. This increase could have negative repressions on the Dutch NCP’s capability to deal with the ever-higher number of cases promptly and effectively. Hence, the allocation of extra human and financial resources to the Dutch NCP must be welcome and, possibly, sought.

Furthermore, the analysis shows that improvements in policies and procedures, transparency, stakeholders’ engagement and grievance mechanisms are the categories of the agreements and recommendations discussed during mediation. The latter three categories concern the relationship of multinational enterprises with societies where they conduct business, and policies and procedures can be part of any type of change needed for improvement. The fact that at least two of the latter three categories are evident in each of the procedures suggests that the relationship between business and society is the important subject in the Dutch NCP procedures. While all categories are important for improvement in the relationship between multinational enterprises and the societies wherein they conduct business, stakeholder engagement can be considered most important. To achieve engagement with stakeholders, a multinational enterprise should provide transparency concerning its business activities in general and access to its grievance mechanism in particular. For instance, transparency on business activities is needed for societies to express their concerns by way of the grievance mechanism. As highlighted by the UNGP, the feedback provided by a grievance mechanism may include insights for improvement in the relationship between a multinational enterprise and the societies where it conducts business activities. Strikingly, the results of the analysis show that agreements and recommendations for improvement regarding grievance mechanisms have shown the least progress in implementation of all the outputs. While at the same time a grievance mechanism receives feedback which provides a multinational enterprise with the opportunity to improve its stakeholder engagement with societies.

Furthermore, by way of monitoring the NCP, one can assess whether a multinational enterprise has actually improved its relationship with stakeholders such as societies, rather than only relying on the judgement of the multinational enterprise. In other words, the Dutch NCP can structurally monitor the implementation of actions that have not been completed and those that have been completed. Which means that it can address further questions regarding how the implementation has taken place, to make sure that the expectations set during mediation are met in the follow-up step. Otherwise, there may be a chance that multinational enterprises will assess their own efforts regarding the extent to which improvement has taken place.

It is worth noting that the Dutch NCP’s task is formally limited to resolving disputes during the NCP procedure. In other words, the Dutch NCP is not required to monitor the implementation of the agreements between the parties involved, as well as NCP’s recommendations. Nonetheless, the achievement of effective RBC improvement oftentimes requires some monitoring activities in the follow-up step. As such, it seems desirable that the Dutch NCP conducts monitoring activities, in addition to the conventional activities of dispute resolution during the NCP procedure.

Moreover, the analysis of the follow-up statements shows that the Dutch NCP provides recommendations in the follow-up statement on the addressed issues. Since this is the end of the procedure, it is not known whether the multinational enterprises have implemented actions to meet them. In other words, the NCP should only conclude the procedure in cases where all significant actions have been implemented to resolve the addressed issue and to prevent its repetition.

Finally, this study contributes to the debate on the contribution of a state-based non-judicial grievance mechanism to RBC improvement by multinational enterprises by showing the importance of monitoring the implementation of mediations results. As addressed in the UNGP, establishing a non-judicial state-based grievance mechanism is important, but to ensure RBC improvement, monitoring must take place during its procedure. When monitoring does not take place, there is risk of little to no improvement in terms of a multinational enterprises’ RBC approach. The Procedural Guidance does not describe expectations on the execution of the follow-up step, and it does not highlight the importance of conducting a follow-up step and monitoring in every NCP procedure. While at the same time, these matters play a significant role in actually achieving the aim of the OECD Guidelines, which is RBC improvement by multinational enterprises.

Further research is needed on how the Procedural Guidance can be improved in terms of providing standards on how effective RBC improvement can be achieved during the follow-up step of the NCP procedure, especially in relation to monitoring. Additionally, research on the output categories is needed to provide insights on whether the combination of these categories contributes to more effective RBC improvement. Most importantly, research is needed on whether and how multinational enterprises have implemented all outputs, and what the impact of this implementation has been on their RBC approach. These insights are necessary for assessing whether a state-based non-judicial grievance mechanism like the NCP indeed contributes to RBC improvement by multinational enterprises. - * The author is thankful for the invaluable feedback provided by Prof. Dr. E. Hey and Prof. Dr. K.E.H. Maas on this article. Corresponding author: mayar@law.eur.nl.

-

1 A. Warhurst, ‘Future Roles of Business in Society: The Expanding Boundaries of Corporate Responsibility and a Compelling Case for Partnership’, 37 Futures 151, at 152 (2005).

-

2 https://nos.nl/nieuwsuur/artikel/2022507-nederlands-farmaciebedrijf-levert-executie-medicijn.html (last visited 9 January 2022).

-

3 www.nporadio1.nl/onderzoek/2253-zo-is-de-nederlandse-overheid-betrokken-bij-milieuschade-in-brazilie (last visited 9 January 2022).

-

4 www.rtlnieuws.nl/geld-en-werk/artikel/1800936/milieudefensie-oeso-klacht-tegen-rabobank (last visited 9 January 2022).

-

5 OECD, OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises 2011 (2011).

-

6 J.C. Ochoa Sanchez, ‘The Roles and Powers of the OECD National Contact Points Regarding Complaints on an Alleged Breach of the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises by a Transnational Corporation’, 84 Nordic Journal of International Law 89, at 90-94 (2015).

-

7 The Procedural Guidance is part of the Amendment of the Decision of the Council on the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. OECD, Procedural Guidance and Commentary on the Implementation Procedures of the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises in OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises 2011 (2011), at 85.

-

8 United Nations, Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (2011), at 27-28.

-

9 OECD, above n. 5, at 3.

-

10 OECD, above n. 7, at 71.

-

11 Ibid., at 72-73.

-

12 Ibid.

-

13 OECD, above n. 7, at 71-75.

-

14 Ibid., at 81-87.

-

15 Ibid.

-

16 Ibid., at 85.

-

17 United Nations, above n. 8, at 33.

-

18 OECD Watch, Remedy Remains Rare: An Analysis of 15 Years of NCP Cases and their Contribution to Improve Access to Remedy for Victims of Corporate Misconduct (2015), at 47.

-

19 J. Ruggie and T. Nelson, ‘Human Rights and the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises: Normative Innovations and Implementation Challenges’, Corporate Social Responsibility Initiative Working Paper 66, at 20 (2015).

-

20 C. Clark, W. Rosenzweig, D. Long & S. Olsen, ‘Double Bottom Line Project Report: Assessing Social Impact in Double Bottom Line Ventures’, Methods Catalog Columbia Business School, at 14 (2004).

-

21 United Nations, above n. 8.

-

22 OECD, Guide for National Contact Points on Structures and Activities, OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (2019), at 11-12.

-

23 K. Buhmann, ‘Public Regulators and CSR: The “Social Licence to Operate” in Recent United Nations Instruments on Business and Human Rights and the Juridification of CSR’, 136 Journal of Business Ethics 699, at 709-711 (2016).

-

24 A. Kun, ‘How to Operationalize Open Norms in Hard and Soft Laws: Reflections Based on Two Distinct Regulatory Examples’, 34 International Journal of Comparative Labour Law and Industrial Relations 23, at 24 (2018).

-

25 J. Southalan, ‘Human Rights and Business Lawyers: The 2011 Watershed’, 90 Australian Law Journal 889, at 896 (2016).

-

26 K. da Costa, ‘Corporate Accountability in the Samarco Chemical Sludge Disaster’, 26 Disaster Prevention and Management 540, at 546 (2017).

-

27 Kun, above n. 24, at 41.

-

28 OECD, above n. 5, at 23.

-

29 Kun, above n. 24, at 41.

-

30 Ibid.

-

31 A. Marx and J. Wouters, ‘Rule Intermediaries in Global Labor Governance’, 670 The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 189, at 192 (2017).

-

32 Ibid., at 192.

-

33 da Costa, above n. 26, at 547.

-

34 D. Carolei, ‘Survival International v World Wide Fund for Nature: Using the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises as a Means of Ensuring NGO Accountability’, 18 Human Rights Law Review 371, at 373 (2018).

-

35 www.oecd.org/investment/mne/oecddeclarationanddecisions.htm (last visited 15 April 2022), the OECD member states are: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States. The non-OECD member states that have adopted the OECD Guidelines are Argentina, Brazil, Croatia, Egypt, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Morocco, Peru, Romania, Tunisia, Ukraine and Uruguay.

-

36 Buhmann, above n. 23, at 702.

-

37 OECD, above n. 5, at 3.

-

38 da Costa, above n. 26, at 547.

-

39 Ochoa Sanchez, above n. 6, at 90-92.

-

40 K. Buhmann, ‘Analysing OECD National Contact Point Statements for Guidance on Human Rights Due Diligence: Method, Findings and Outlook’, 36 Nordic Journal of Human Rights 390, at 391 (2018).

-

41 OECD, above n. 5, at 3.

-

42 OECD, above n. 7, at 71-73.

-

43 Ibid., at 77.

-

44 Ibid., at 71.

-

45 www.oecdguidelines.nl/ncp/ncp-members (last visited 9 January 2022).

-

46 www.oecdguidelines.nl/ncp/documents/publication/2014/07/01/ncp-establishment-order-2014 (last visited 9 January 2022).

-

47 www.oecdguidelines.nl/ncp (last visited 9 January 2022).

-

48 OECD, above n. 7, at 71-73.

-

49 Carolei, above n. 34, at 373.

-

50 K.A. Reinert, O.T. Reinert & G. Debebe, ‘The New OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises: Better but Not Enough’, 26 Development in Practice 816, at 819 (2016).

-

51 Buhmann, above n. 40, at 391.

-

52 OECD, above n. 7, at 72-73.

-

53 Buhmann, above n. 40, at 391.

-

54 Carolei, above n. 34, at 373.

-

55 OECD, above n. 7, at 82.

-

56 OECD, Coordination between OECD National Contact Points during Specific Instance handling (2019), at 7.

-

57 S. van ‘t Foort, ‘Due Diligence and Supply Chain Responsibilities in Specific Instances’, 4 Erasmus Law Review 61, at 64 (2019).

-

58 S. van ‘t Foort, T. Lambooy & A. Argyrou, ‘The Effectiveness of the Dutch National Contact Point’s Specific Instance Procedure in the Context of the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises’, 16 McGill Journal of Sustainable Development Law 194, at 201-5 (2020).

-

59 van ‘t Foort, above n. 58, at 228.

-

60 Ibid., at 229-30.

-

61 https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0035293/2014-12-20 (last visited 9 January 2022). OECD, above n. 7, at 71-87.

-

62 OECD, above n. 7, at 85.

-

63 Ibid., at 81-87.

-

64 Ibid.

-

65 Ibid.

-

66 Ibid.

-

67 Ibid., at 73.

-

68 Ibid.

-

69 Ibid.

-

70 Ibid.

-

71 Ibid.

-

72 Ibid., at 85.

-

73 Ibid.

-

74 Ibid.

-

75 Ibid.

-

76 Clark, above n. 20, at 14.

-

77 Ibid.

-

78 Ibid.

-

79 Ibid., at 14.

-

80 Ibid.

-

81 https://mneguidelines.oecd.org/Flyer-OECD-National-Contact-Points.pdf (last visited 9 January 2022).

-

82 United Nations, above n. 8, at 27.

-

83 Ibid., at 33.

-

84 Ibid., at 27.

-

85 Ibid.

-

86 Ibid., at 28.

-

87 Ibid., at 33-35.

-

88 Ibid., at 27.

-

89 Ibid., at 33-35.

-

90 Ibid., at 30.

-

91 Ibid., at 28.

-

92 Dutch NCP, Bart Stapert, attorney v. Mylan (2016).

-

93 Dutch NCP, Both END et al. v. Atradius Dutch State Business (2016).

-

94 Dutch NCP, Friends of the Earth / Milieudefensie v. Rabobank (2016).

-

95 Dutch NCP, Houd Friesland Mooi! v. Nuon Enerdy N.V. (2018).

-

96 Dutch NCP, Oxfam Novib, Greenpeace Netherlands, BankTrack and Friends of the Earth Netherlands (Milieudefensie) v. ING (2019).

-

97 Dutch NCP, Former Employees of Bralima v. Bralima and Heineken (2017).

-

98 Dutch NCP, IUF v. Perfeti Van Melle (2020).

-

99 Dutch NCP, FIVAS, the Initiative to Keep Hasankeyf Alive and Hasankeyf Matters v. Bresser (2018).

-

100 United Nations, above n. 8, at 23.

-

101 Dutch NCP, Both ENDS et al. v. Atradius Dutch State Business (2018).

-

102 Dutch NCP, Friends of the Earth / Milieudefensie v. Rabobank (2018).

-

103 Dutch NCP, Both ENDS et al. v. Atradius Dutch State Business (2018).

-

104 Dutch NCP, Friends of the Earth / Milieudefensie v. Rabobank (2018).

-

105 Dutch NCP, FIVAS, the Initiative to Keep Hasankeyf Alive and Hasankeyf Matters v. Bresser (2021).

-

106 Dutch NCP, Bart Stapert, attorney v. Mylan (2017).

-

107 Dutch NCP, Both ENDS et al. v. Atradius Dutch State Business (2018).

-

108 Dutch NCP, Hou Friesland Mooi v. Nuon Energy N.V. (2020).

-

109 Dutch NCP, FIVAS, the Initiative to Keep Hasankeyf Alive and Hasankeyf Matters v. Bresser (2021).

-

110 Ibid.

-

111 Dutch NCP, Former Employees of Bralima v. Bralima and Heineken (2021).

-

112 Ibid.

-

113 K. Bhatt and G. Erdem Türkelli, ‘OECD National Contact Points as Sites of Effective Remedy: New Expressions of the Role and Rule of Law within Market Globalization?’ 6 Business and Human Rights Journal 423, at 445 (2021).

-

114 Van ‘t Foort, above n. 58, at 227.

-

115 Dutch NCP, IUF v. Perfetti Van Melle (2021).

-

116 Dutch NCP, Bart Stapert, attorney v. Mylan (2017).

-

117 Dutch NCP, Oxfam Novib, Greenpeace, BankTrack, Milieudefensie v. ING (2020).

Erasmus Law Review |

|

| Article | The NCP Procedure of the OECD Guidelines: Monitoring and RBC Improvement during the Follow-Up Step |

| Trefwoorden | OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, Responsible Business Conduct, NCP procedure, UNGP, monitoring |

| Auteurs | Aziza Mayar * xThe author is thankful for the invaluable feedback provided by Prof. Dr. E. Hey and Prof. Dr. K.E.H. Maas on this article. Corresponding author: mayar@law.eur.nl. |

| DOI | 10.5553/ELR.000216 |

|

Toon PDF Toon volledige grootte Samenvatting Auteursinformatie Statistiek Citeerwijze |

| Dit artikel is keer geraadpleegd. |

| Dit artikel is 0 keer gedownload. |

Aziza Mayar, "The NCP Procedure of the OECD Guidelines: Monitoring and RBC Improvement during the Follow-Up Step", Erasmus Law Review, 1, (2022):1-11

|

The National Contact Point specific instance procedure of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises is expected to contribute to improvements in responsible business conduct of multinational enterprises. The aim of this article is to examine whether and how the Dutch National Contact Point uses its discretion, provided for the implementation of the procedure, to achieve this aim. To provide insight into this matter, an analytical framework based on Clark et al. (Double Bottom Line Project Report) and the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights was developed and used to assess the information provided in statements of the Dutch National Contact Point procedures. This framework shows that monitoring is crucial for achieving improvements in responsible business conduct by multinational enterprises. Moreover, the analysis illustrates that the Dutch National Contact Point hardly uses its discretion to monitor the results of mediation during the procedures. Consequently, responsible business conduct improvement during the procedures analysed in this article has not been clearly secured. This is largely attributed to the fact that not all agreements and recommendations of mediation had been implemented by the end of the procedures. Furthermore, this research indicates that the National Contact Point procedure should continue until a multinational enterprise has taken all the necessary efforts to meet the results of mediation. It concludes that if the National Contact Point does not assess this effort by way of monitoring during the procedure, there will be continued uncertainty regarding the actual improvements in responsible business conduct approaches of multinational enterprises. |