-

1 Introduction

“Our competitors are our friends; our customers are the enemy”

Ringleader of a certain Cartel, quoted by OECD1x OECD, Hard Core Cartels (2000), at 5.In this article, the author shall argue that criminal sanctions should be introduced in the European Union (EU) to effectively tackle and deter cartel activities. The word cartel, popularised amongst the masses through crime dramas, evokes strong public sentiments. Corporate cartels are depicted in popular media as a sign of a decadent corporate culture which has permeated our society.2x A. Stephan, ‘The Battle for Hearts and Minds: The Role of the Media in Treating Cartels as Criminal’, in C. Beaton-Wells and A. Ezrachi (eds.), Criminalising Cartels (2011) 111, at 129. Many believe that cartel activities constitute a public welfare crime and evil of the highest order.3x T.O. Barnett, ‘Criminal Enforcement of Antitrust Laws: The U.S. Model’, United States Department of Justice (2006), www.justice.gov/atr/speech/criminal-enforcement-antitrust-laws-us-model (last visited 17 November 2022). The US Supreme Court did not mince words, when it referred to cartels as the supreme evil of antitrust.4x Verizon Communications v. Law Offices of Curtis Trinko (2004) 124 S. Ct. 872. The OECD too has pushed for the criminalisation of hardcore cartel activities for decades.5x OECD, above n. 1, at 5. Nonetheless, the EU has continued to avoid criminal sanctions as a tool for cartel enforcement. Two reasons may explain this: first, there is a consensus at the European level that fines can have as much deterrence as imprisonment and that there does not exist sufficient justification in cartel activities to impose criminal deterrence.6x P. Whelan, The Criminalization of European Cartel Enforcement (2014), at 44-78. Second, given EU’s unique political structure, it is difficult to come up with a one-fits-all criminal enforcement system.7x Id., at 260-88.

As per scholars such as Milton and Sokol, criminalisation of individuals involved in cartel activities is a must, given that it has the probability of creating indefinite deterrence and providing a reasonable alternative to ever-burgeoning fines.8x E. Milton, ‘Putting the Price-Fixers in Prison: The Case for the Criminalisation of EC Competition Law’, 5 Hibernian Law Journal 159 (2005); D. Sokol, ‘Reinvigorating Criminal Antitrust?’, 60 William & Mary Law Review 1545 (2019). On the other hand, an equally large number of scholars argue that cartel activities should not be criminalised. Lewisch argued that criminal sanctions should only be used as an ultima ratio when other legal and institutional remedies fail to accomplish the required levels of deterrence effectively.9x P. Lewisch, ‘Enforcement of Antitrust Law: The Way from Criminal Individual Punishment to Semi-Penal Sanctions in Austria’, in K.J. Cseres, M.P. Schinkel & F.O.W. Vogelaar (eds.), Criminalization of Competition Law Enforcement (2006) 290, at 303. In the case of cartels, given the enforcement options available, Lewisch found it unnecessary to advocate individual criminal sanctions. Another set of scholars has relied on moral grounds to argue that cartels deserve criminal punishment, as they involve a high level of deceit.10x A. Macculloch, ‘The Cartel Offence: Defining an Appropriate Moral Space’, 8(1) European Competition Journal 73, at 93 (2012). They are countered by others who believe that the introduction of subjective morality in antitrust will undermine its rational basis in law and economics.11x B. Fisse, ‘The Proposed Australian Cartel Offence: The Problematic and Unnecessary Element of Dishonesty’, Sydney Law School Legal Studies Research Paper No 06/44 2006.

This article seeks to present a perspective on this debate by making use of economic analysis and available statistics. Tools including the economic theory of harm, cost-benefit analysis of deterrence, Becker’s optimal deterrence theory, normative analysis of sanctions and comparative analysis of enforcement statistics, primarily from the EU and the US, are utilised. The big question that this article addresses is whether the current cartel enforcement mechanism in the EU, based on ever-increasing amounts of corporate fines, is sufficient and justified, or must we introduce a criminal enforcement mechanism to supplement the deterrence framework? The allied questions that are dealt with in the article are: first, whether criminal sanction of individuals involved in cartel activities is theoretically and morally justified; second, how will criminal sanctions improve the deterrence effect; and third, how do we structure a possible criminal enforcement model and what basic principles must be followed?

In pursuance of these questions, the article first studies the divergent approaches to criminalisation of the cartel offence taken by various jurisdictions. The focus is on the law as it is in the US, the UK and the EU. This section also defines what is meant by the words cartel activities and criminal liability in the context of this article.

In Section 3, data on cartel busting in the EU and the US are surveyed. This survey aims to understand if there has been sufficient deterrence through the fine-based model used in the EU. The fact that new cartels are being discovered frequently even as the size of fines keeps on growing is often highlighted as proof that the current model may not be the optimal one.12x K.J. Cseres, M.P. Schinkel & F.O.W. Vogelaar,’ Law and Economics of Criminal Antitrust Enforcement: An Introduction’, in K.J. Cseres, M.P. Schinkel & F.O.W. Vogelaar (eds.), Criminalization of Competition Law Enforcement (2006) 1, at 1-2. This article digs deeper into this argument by investigating three statistics: number of cartel decisions adopted by the European Commission; the cumulative amount of the fines being imposed; and number of cartel investigations in the US. This analysis forms the basis of a claim that fines have not been creating optimal deterrence.

Section 4 tackles the question of whether cartel activities are a crime. It involves dealing with the question of what is a crime and when are criminal sanctions truly justified. After all, overcriminalisation is never a good option, and if there is doubt as to the necessity of criminal sanctions, it is better not to criminalise the activity.13x P.J. Larkin, ‘Public Choice Theory and Overcriminalization’, 36(2) Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy 715, at 760 (2013); D. Kim and I. Kim, ‘Trade-offs in the Allocation of Prosecution Resources: An Opportunity Cost of Overcriminalization’, 47(16) Applied Economics 1652, at 1669 (2015). In this section, making use of theories on criminal justice, the article shows that cartels constitute a criminal offence because they cause harm to the society at large, there is public opinion in favour of criminalisation, and there is sufficient moral reasoning to justify criminal sanctions.

Section 5 provides objective justifications for criminalisation. This is done by showing that exorbitant fines are not ideal deterrence tools as they do not target the actual wrongdoers, can never be optimum and are socially undesirable. This section further shows that criminal sanctions can help us stop the fines juggernaut and instead implement a less costly and effective tool of deterrence.

Section 6 grapples with the challenges which can arise with criminalisation and proposes three basic principles which must be followed in such a process. It first highlights various types of cartel activities which must be dealt with through different measures. Then it stresses the importance of procedural fairness and the need to create a criminal cartel enforcement system which is independent of the European Commission. Lastly, it discusses the importance of a leniency programme which is interlinked with leniency applications to the Commission. -

2 A Divergence the Size of the Atlantic: Approaches to Cartel Enforcement

European countries and the US, both at the forefront of cartel enforcement, have a surprisingly major divergence when it comes to the use of criminal sanctions. While the EU relies primarily on a combination of fines, its leniency programme, and a whistle-blower tool to discover and punish cartels,14x European Commission, ‘Cartels Overview’, https://competition-policy.ec.europa.eu/cartels/cartels-overview_en (last visited 29 January 2023). in the US, participating in cartel activities constitutes a major antitrust crime and has been so for almost a century. Section 1 of the Sherman Act, which was enacted as early as 1890, outlaws ‘every contract, combination, or conspiracy in restraint of trade,’ engaging in which may result in both fines and imprisonment up to 10 years (increased in 2004 from 3 years). In Standard Oil v. United States (1911), this was interpreted by the US Supreme Court to mean ‘unreasonable’ restraint. There are both historical and practical reasons behind the American reliance on criminal sanctions. Historically, the American public had an image of ‘robber barons’, which made cartel busting a very popular electoral demand, leading to imposition of criminal sanctions (which is also addressed in this article in Section 4).15x D. Baker, ‘Why Is the United States So Different from the Rest of the World in Imposing Serious Criminal Sanctions on Individual Cartel Participants’, 12 Sedona Conference Journal 301, at 304 (2011). On a practical note, the US Antitrust Division, after extensive interviews and research has found, ‘international cartels that operated profitably and illegally in Europe, Asia and elsewhere around the world did not expand their collusion to the United States solely because the executives decided it was not worth the risk of going to jail,’ a very strong evidentiary basis to retain, enforce and even expand the criminal sanction.16x US Department of Justice, ‘Cartel Enforcement in The United States (and Beyond)’ (6 February 2007), www.justice.gov/atr/speech/cartel-enforcement-united-states-and-beyond#N_5_ (last visited 29 January 2023). Over 246 individuals were convicted for cartel-related crimes in the 2000-2010 decade.17x B. Howell, ‘Sentencing of Antitrust Offenders: What Does the Data Show?’ (2010) www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/about/commissioners/selected-articles/Howell_Review_of_Antitrust_Sentencing_Data.pdf (last visited 17 November 2022). In the 2011-2020 decade, over 350 individuals have been charged for engaging in cartels.18x US Department of Justice, ‘Criminal Enforcement Trend Charts’ (16 November 2021), www.justice.gov/atr/criminal-enforcement-fine-and-jail-charts (last visited 17 November 2022).

On the other side, in Europe however, criminalisation of individuals and firms engaged in cartels has been lacklustre.19x K. Jones and F. Harrison, ‘Criminal Sanctions: An Overview of EU and National Case Law’, Concurrences N° 64713 (2015), http://awa2015.concurrences.com/articles-awards/business-articles-awards/article/criminal-sanctions-an-overview-of-eu-and-national-case-law (last visited 17 November 2022). In the UK, even though criminalisation of cartels has been a priority, success has been limited (as of now, only one proper conviction and one plea-deal has been achieved).20x In 2017, a conviction was achieved in the Precast Concrete Drainage Products, [2017] CE/9705/12; and between 2003-2012 only one conviction in the Marine Hose cartel case was achieved as part of a plea deal – Regina v. Whittle, [2008] EWCA Crim 2560; ‘U.K. Imposes First Criminal Sentences On Cartel Participants’, Cleary Gottlieb (2 July 2008), www.clearygottlieb.com/~/media/organize-archive/cgsh/files/publication-pdfs/uk-imposes-first-criminal-sentences-on-cartel-participants.pdf (last visited 17 November 2022). In the UK, Water Tanks cartel case (2015), executives accused of cartel crimes were acquitted by the jury, exposing the dilemma of whether there is sufficient public disapprobation against cartel activities.21x ‘The future of the criminal cartel offence in the UK’, NRF (January 2021), www.nortonrosefulbright.com/en/knowledge/publications/51dd9da8/the-future-of-the-criminal-cartel-offence-in-the-uk (last visited 17 November 2022). To enhance the effectiveness of the cartel offence, the country has made amendments to the definition of the offence by removing an element of dishonesty, elevating it to a strict liability crime.22x C. Swaine, ‘Criminalising Competition Law: The Struggle for Real and Effective Enforcement in Ireland and beyond within the Reality of New Globalised European Order’, 14 Irish Journal of European Law 203 (2007).

In the EU criminalisation of cartels has largely been absent. Some Member States like Greece,23x Art. 44, Greek Law 3959/2011. France,24x Art. L420-6, French Commercial Code 2008. Romania25x Art. 63, Romanian Competition Law no. 21/1996. and Denmark26x A. Christensen and K.H. Skov, ‘Increased Use of Personal Fines in Denmark for Competition Law Violations’, Antitrust Alliance, http://antitrust-alliance.org/increased-use-of-personal-fines-in-denmark-for-competition-law-violations/ (last visited 17 November 2022). do criminalise various cartel activities, but rarely use these laws to imprison executives.27x Peter Whelan, ‘Antitrust Criminalization as a Legitimate Deterrent’, in T. Tóth (ed.), The Cambridge Handbook of Competition Law Sanctions (2021) 101; Jones and Harrison, above n. 19. Other states like Germany, Hungary, Poland and Italy continue to have laws criminalising bid rigging, a form of cartels wherein state resources are abused.28x Sec. 298, German Criminal Code; Art. 353, Italian Criminal Code; Art. 305, Polish Penal Code (1997); and Art. 296/B, Hungarian Criminal Code (1978). These laws, however, are rarely used to imprison individuals.29x Jones and Harrison, above n. 19. It can safely be concluded that the preferred position in the EU is to deter and punish cartels through fines and private enforcement,30x H. Ullrich, ‘Private Enforcement of the EU Rules on Competition – Nullity Neglected’, 52 International Review of Intellectual Property and Competition Law 606, at 635 (2021). and criminal charges are not prominent in the equation. Article 101(1) TFEU prohibits various cartel activities. It reads,all agreements between undertakings, decisions by associations of undertakings and concerted practices which may affect trade between Member States and which have as their object or effect the prevention, restriction or distortion of competition within the internal market shall be void.

Specifically, prohibited practices include price-fixing, production controls, market sharing and collusion to exclude competitors. The European Commission (EC or the ‘Commission’) is the primary watchdog implementing the law, and has used large fines to deter cartels.31x M. Mariniello, ‘Do European Fines Deter Price Fixing?’, VoxEU (22 September 2013), https://voxeu.org/article/do-european-fines-deter-price-fixing (last visited 17 November 2022). As provided under the Fining Guidelines (2006), a fine of up to 10% of total global turnover may be imposed on the delinquent companies.32x P. Chappatte and P. Walter, ‘The Cartels and Leniency Review: European Union’, The Laws Reviews (1 February 2022), https://thelawreviews.co.uk/title/the-cartels-and-leniency-review/european-union (last visited 17 November 2022); European Commission, Guidelines on the method of setting fines imposed pursuant to Art. 23(2)(a) of Regulation No 1/2003 (2006/C 210/02).

Private enforcement has also been made a possibility after the CJEU judgement in Courage33x C-453/99, Courage Ltd v. Bernard Crehan, [2001] ECR. and was also made relatively easier through the Damages Directive (2014/104/EU).34x C. Migani, ‘Directive 2014/104/EU: In Search of a Balance between the Protection of Leniency Corporate Statements and an Effective Private Competition Law Enforcement’, 7 Global Antitrust Review 81 (2014); P.L. Parcu and M.A. Rossi, ‘The Role of Economics in EU Private Antitrust Enforcement: Theoretical Framework, Empirical Methods and Practical Issues’, in P.L. Parcu, G. Monti & M. Botta (eds.), Private Enforcement of EU Competition Law: The Impact of the Damages Directive (2018) 62.Rise in claims filed. (Laborde, above n. 35.)

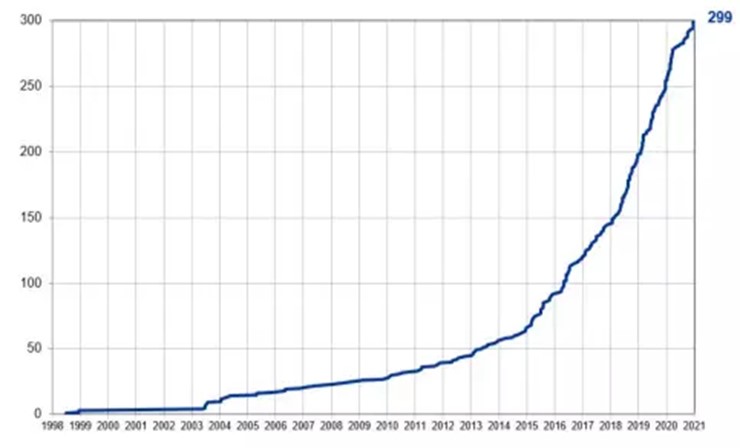

Over fifty-eight damage awards have been handed by the national courts to claimants in over 299 claims filed.35x Jean-François Laborde, ‘Cartel Damages Actions in Europe: How Courts Have Assessed Cartel Overcharges’, Concurrences (September 2021), www.concurrences.com/en/review/issues/no-3-2021/pratiques/102086 (last visited 17 November 2022). As can be observed in Figure 1, this rise has been nothing short of sensational. The rise of private enforcement, nonetheless, has not improved deterrence as it has presented a Catch-22 situation with respect to leniency, which forms the backbone of detecting cartel cases.36x C. Aubert, P. Rey & W.E. Kovacic, ‘The Impact of Leniency and Whistle-Blowing Programs on Cartels’, 24 International Journal of Industrial Organization 1241 (2006). Since those undertakings which disclose cartel activities under a leniency programme would still be subject to private claims, the rise of private claims has seen a concomitant decline in leniency applications.37x L. Hornkohl, ‘A Solution to Europe’s Leniency Problem: Combining Private Enforcement Leniency Exemptions with Fair Funds’, Kluwer Competition Law Blog (18 February 2022), http://competitionlawblog.kluwercompetitionlaw.com/2022/02/18/a-solution-to-europes-leniency-problem-combining-private-enforcement-leniency-exemptions-with-fair-funds/ (last visited 17 November 2022). As per a report, the number of leniency applications has declined, ‘from forty-six in 2014, to thirty-two in 2015, twenty-four in 2016, eighteen in 2017, seventeen in 2018, fifteen in 2019, and just four in 2021’.38x E.A. Rodriguez and R. Noorali, ‘Less Co-operation, More Challenge’, 19(1) Competition Law Insight 1 (2020); ‘Spill the Beans: The European Commission Publishes New Guidance on Its Leniency Policy and Practice’, Morrison Foerster (15 November 2022), www.mofo.com/resources/insights/221115-spill-the-beans-the-european-commission#_ftn3 (last visited 29 January 2022). Thus, in one way or the other, it is fines, whether through public or private enforcement, which are central to cartel enforcement in the EU.

Before we move any further, it is also pertinent to clarify what is meant by cartel activities, which has been referred to continuously in this article. In the author’s view, cartel activities include both, the actual anti-competitive collusion by firms and the preparatory activities undertaken by the agents of these firms. Thus, when the article talks about criminalisation of cartel activities, it refers to both corporate criminal liability and criminal liability for responsible executives. Both these liabilities are interlinked, given that corporate firms after all are non-living legal individuals. Criminal liability of corporates is satisfied through the identification doctrine, which involves identifying the individuals responsible for the actions of the firm or those who are the ‘directing mind and will’ behind the concerned decisions.39x S. Yoder, ‘Criminal Sanctions for Corporate Illegality’, 69 Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology 40 (1978). Corporate criminal liability, albeit, can also give rise to a broader responsibility for the directing minds as it also entails vicarious liability.40x UK Law Commission, Corporate Criminal Liability: An Options Paper (2022), at 13-19.

It is also necessary to remark at this stage that the concept of corporate criminal liability has not evolved in the EU to the extent it has in common law countries. In common law, the historical development of corporate criminal liability was a natural consequence of misfeasance rulings in cases like Queen v. Great North of England Railway Co. (1846).41x [1846] 115 Eng. Rep. 1294 (Q.B.); V.S. Khanna, ‘Corporate Criminal Liability: What Purpose Does It Serve?’, 109(7) Harvard Law Review 1477, at 1534 (1996). By 1909, the US Supreme Court had already held a corporation liable for criminal conduct in New York Central & Hudson River Railroad Co. v. United States.42x [1909] 212 US 481. In European countries, however, the principle of societas delinquere non potest was still applied until the late 80s.43x L.H. Leigh, ‘The Criminal Liability of Corporations and Other Groups: A Comparative View’, 80(7) Michigan Law Review 1508, at 1528 (1982). This principle implies that societies or legal bodies cannot commit crimes. While that principle has since been abandoned and some countries have already introduced criminal liability for corporates,44x G. Vermeulen, W.D Bondt & C. Ryckman, Liability of Legal Persons for Offences in the EU (2012); J. Gobert & A.-M. Pascal, European Developments in Corporate Criminal Liability (2011). many countries are yet to introduce laws on corporate criminal liability.Table 1Period Decisions 1990-1994 10 1995-1999 9 2000-2004 29 2005-2009 33 2010-2014 31 2015-2019 26 ++2020-2022++ 14 Germany, for instance, published a draft Corporate Sanctions Act introducing criminal liability, which has now been withdrawn.45x E. Brunelle et al., ‘Global Enforcement Outlook: Europe’s Evolving Corporate Criminal Liability Laws’, FBD (25 January 2022), https://riskandcompliance.freshfields.com/post/102hh57/global-enforcement-outlook-europes-evolving-corporate-criminal-liability-laws (last visited 17 November 2022). Further, the European Public Prosecutor’s Office (EPPO), the world’s first supranational public prosecutor’s office, started its work in 2021 and is tasked with investigating corporate financial offences. Thus, imposing corporate criminal liability for cartel delinquency in the EU may be difficult but is certainly possible.

-

3 The State of Cartels in the EU and in the US

For any argument for a change in the enforcement model to stand, it is pertinent to establish that the current model is unable to achieve optimum control over the malignant activities. While the next section will detail why cartels are problematic and how their optimum deterrence may be achieved, this section focuses on current statistics related to cartel operations in the EU. The three statistics that we are concerned with are: first, number of cartel decisions adopted by the Commission; second, the cumulative fines being imposed; and third, the number of cartel investigations in the US.

The number of cartel decisions adopted by the Commission would tell us if the current enforcement system would help to reduce the number of cartels in existence. If the number of cartel decisions being adopted is stagnant, it may lead to two alternate conclusions: first, it may mean that the number of cartels being prosecuted is stagnant because of an improvement in the rate of detection, even as the number of cartels in existence has reduced. As the Becker model has proven with simplicity, the incentive to commit a crime is a result of the net benefit (B) the criminal derives after deducting the expected cost of punishment (C) combined with the probability of detection (P).46x N. Garoupa, ‘Economic Theory of Criminal Behavior’, in G. Bruinsma and D. Weisburd (eds.), Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice (2018) 1280, at 1286. If this number is positive, then crimes would continue unabated. To create optimal deterrence, the following result must be obtained: 0 > (B – PC). Thus, it is very probable that a stagnant number of cartels being prosecuted is a sign that the number of cartels has reduced due to optimal deterrence as a result of high fines and increased detection rates. This argument, however, would be deficient if it can be shown that there has been no concrete change in the rate of detection. In that case, a second conclusion would be more logical: that there has been no significant reduction in the number of cartels in existence.

The data is consistent with this analysis. After an initial spike in the number of decisions adopted in the 2000s, the number of decisions being adopted has more or less stagnated at around thirty decisions every 5 years, as can be observed in Table 1.47x European Commission, ‘Statistics on Cartel Cases’, https://ec.europa.eu/competition-policy/cartels/statistics_en (last visited 17 November 2022).

One may also observe that the number of decisions being adopted peaked in the 2005-2009 period, and has since been on a gradual decline. This may be explained by the fact that after a temporary rise in the number of leniency applications, which gave a significant boost to cartel detection, detection has been on a decline.48x A. Amos, ‘Impact of the European Commission’s Leniency Policy in Relation to Cartels’, New Jurist (12 August 2016), https://newjurist.com/impact-of-the-european-commission-leniency-policy-in-relation-to-cartels.html (last visited 17 November 2022). During 2002-2005, over two-thirds of the decisions were based on leniency application.49x H.W. Friederiszick and F.P. Maier-Rigaud, ‘The Role of Economics in Cartel Detection in Europe’, in D. Schmidtchen, M. Albert & S. Voigt (eds.), The More Economic Approach to European Competition Law (2007) 179. The leniency regime has experienced a significant slowdown since then.50x J. Ysewyn and S. Kahmann, ‘The Decline and Fall of the Leniency Programme in Europe, Concurrences (2018), www.cov.com/-/media/files/corporate/publications/2018/02/the_decline_and_fall_of_the_leniency_programme_in_europe.pdf (last visited 17 November 2022). While a host of reasons including the risk of spillover effects and the introduction of the marker regime in 2006 are blamed, the disjunction with the 2014 damages directive, as mentioned in the introduction, is seen asTable 2Period Cumulative Fines

(in Billion Euros)Average Fines per Delinquent Undertaking (in Million Euros) 1990-1994 0.34 1.83 1995-1999 0.27 6 2000-2004 3.1 19.9 2005-2009 7.8 39.2 2010-2014 7.6 42.3 2015-2019 8.2 76.6 the primary reason behind the decline of leniency.51x Id. This is observed in the falling numbers of decisions being adopted and supports the possibility that the probability of detection remains low, and the number of cartels in existence continues to be stagnant.

This argument is also supported by economic analysis. A study of the birth and detection cycles of all cartels convicted in the EU between 1969 and 2007 showed that over these decades the detection rate averaged from about 12.9 to 13.3%.52x E. Combe, C. Monnier & R. Legal, ‘Cartels: The Probability of Getting Caught in the European Union’, BEER Paper No. 12 2008. The report found that despite changes in cartel enforcement regulations, cartels continued to exist without significant reduction in their numbers. They found that stricter fines and better detection merely changed the number of years a cartel remained in existence, making shorter periods of collusion more attractive. In another study of cartels convicted in the EU between 1975 and 2009, it was found that despite rising fines, the number of cartels in existence has been plentiful and cartelisation remains a profitable proposition.53x E. Combe and C. Monnier, ‘Fines Against Hard Core Cartels in Europe: The Myth of Over Enforcement’, 56(2) The Antitrust Bulletin 235 (2011).

Another study, by Levenstein and Suslow, looked into cartel stability. Based on cartel lifetimes and collusion profitability studies, they found that cartels are very agile socio-economic institutions, which can counter changes in the legal scenario by adjusting collusion agreements, improving monitoring mechanisms and adjusting the cartel life cycle.54x M.C. Levenstein and V.Y. Suslow, ‘What Determines Cartel Success?’, 44(1) Journal of Economic Literature 43 (2006). In another study, they also argued that cartels in some industries persist in a recurring manner in short intervals, making it even more difficult to detect them.55x M.C. Levenstein and V.Y. Suslow, ‘Breaking Up Is Hard to Do: Determinants of Cartel Duration’, 54 Journal of Law & Economics 455 (2011). These studies combined with the data that the Commission continues to prosecute a more or less stagnant number of cartels, despite rising fines, show that deterrence of cartelisation has not seen a gradual improvement. In terms of the Becker equation, the probability (P) has remained unchanged and rising fines (C) have not generated much marginal deterrence due to cartel profitability.

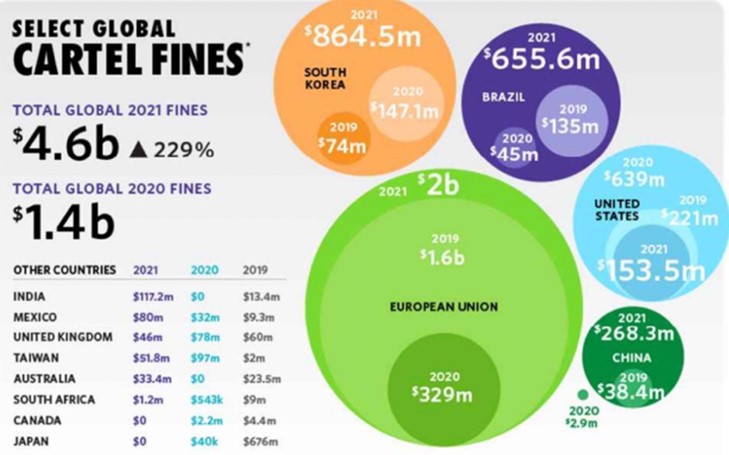

The second key statistic is that of fines. Ever-increasing fines would be a clear indication that deterrence is not strong enough, if despite increased fines, similar numbers of cartels continue to be detected. This is how the second statistic of the total fines being imposed becomes relevant. We have already seen that while the number of cartels convicted is stagnant, the fines have increased by leaps and bounds.56x F.W. Papp, ‘Compliance and Individual Sanctions in the Enforcement of Competition Law’, in J. Paha (ed.), Compliance and Individual Sanctions for Competition Law Infringements 137-38 (2016). If studied in 5-year periods (Table 2), the fines increased from just over 300 million Euros in the 1990-1994 period to over three billion Euros in the 2000-2004 period: a ten-fold leap.57x European Commission, above n. 48. In the 2015-2019 period, it further increased to eight billion Euros, an impressive 250% rise. This was the highest five yearly fine imposed in the EU. The US, in contrast, imposed around 4.5 billion dollars in fines in the same period.58x US Department of Justice, above n. 18. These numbers look even more glaring when we take into account the fine imposed per undertaking. In 1990-1994, it was under two million Euros, increasing to twenty million Euros in 2000-2004. It again doubled to forty million Euros in 2010-2014, and redoubled to eight million Euros during 2015-2019. Thus, there is no denying that the size of fines in the EU has been increasing exponentially, consistent with Becker’s theory that fines should be set to the maximum possible penalty to achieve the most cost-effective deterrence.59x M. Polinsky and S. Shavell, ‘The Optimal Use of Fines and Imprisonment’, 24(1) Journal of Public Economics 89, at 99 (1984). However, as has been established, larger fines have not led to a decrease in the number of cartels in existence, bringing into question the policy of placing sole reliance on fines.Individual and corporate fines

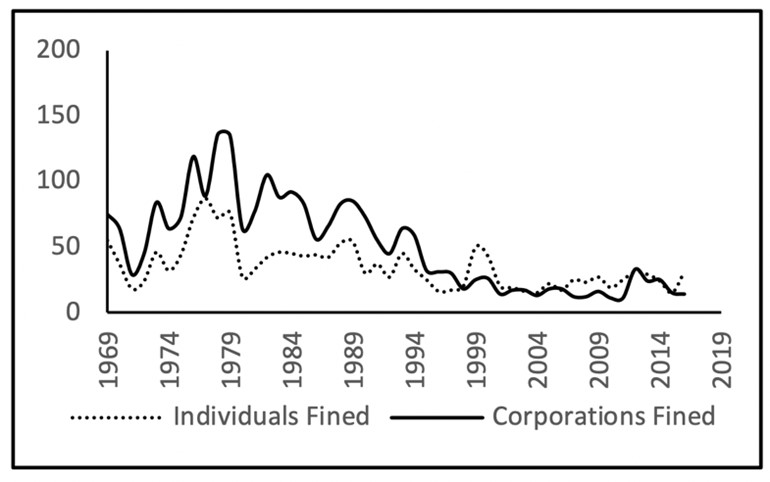

The third statistic of note is the number of cartel investigations in the US. Since the article seeks to propose that criminalisation of cartels should be undertaken, it is pertinent to display that the US has a better functioning deterrence system. While it is impossible to tell with certainty if the number of cartels in the US is in decline, but a good measure of the same is the number of cartel investigations being undertaken. The number of cartels prosecuted has shown an erratic but observable decline. While in 2012 over sixteen firms were prosecuted, by 2018 it was down to five. Similarly, the number of individuals charged has come down from sixty-three in 2012 to the range of twenty-five during 2018-2021. Similarly, a decline in the total penalty imposed has been observed. After peaking in 2015 at over 3.6 billion dollars, total fines and penalties imposed on cartels has not crossed 500 million dollars in any year, and has even been as low as sixty-seven million dollars in 2018.

As one can observe in Figure 2, this trend is also observable in longer time frames. The total number of individuals and corporations convicted has been in a precipitous decline after peaking in the 1970s.60x V. Ghosal and D. Sokol, ‘The Rise and (Potential) Fall of U.S. Cartel Enforcement’, 2020 University of Illinois Law Review 471 (2020). These statistics can lead to two possible conclusions: one that the probability of cartel detection has fallen, leading to reduced prosecutions and fines; or that the level of detection is the same or better but the number of actual cartels has reduced due to improving deterrence. Since no significant policy change has taken place to justify the first conclusion, it makes for a valid claim that the deterrence against cartels has been increasing due to the increased use of criminal penalties against individuals involved in cartels.

Taken together, these three statistics tell us a lot about the state of cartels in the EU. They continue to exist without much deterrence emanating from the rising fines, whereas in the US, there has been a marked decline in the number of cartels, possibly due to criminal sanctions. This conclusion provides a very good reason for us to re-examine the current enforcement system and determine if it can be modified to include criminal sanctions in the form of individual fines, probation, reprimands, and in a worst-case scenario, imprisonment. But to make an effective proposal on imprisonment, two hurdles must be crossed: first, a normative one, displaying that criminal sanctions for cartel activities is justifiable; and second, an objective one, displaying that imprisonment can alter the deterrence level and that a further increase in fines is not optimal. -

4 Can Criminal Sanctions for Cartel Activities Be Normatively Justified?

In this section, the article will display that criminalisation of cartels can be normatively and morally justified. Criminal justice scholar Bill Stuntz, a long-time critic of overcriminalisation and regulatory crimes, has justly argued that criminalisation should not be a recourse for mere regulatory offences but only for ‘core’ harm-based offences.61x D.C. Richman, ‘Overcriminalization for Lack of Better Options: A Celebration of Bill Stuntz’, in M. Klarman, D. Skeel & C. Steiker (eds.), The Political Heart of Criminal Procedure: Essays on Themes of William J. Stuntz 3-5 (2012). To achieve the high threshold of justifying the criminalisation of cartel activities, we must thus prove harm and display that such harm attacks the very ‘core’ of our being. For this, we must search for answers in the philosophy of criminal law and find out what makes crime a crime, and if cartel activities fit the bill. Criminal justice systems in most societies seek to control behaviour which may cause harm to others.62x A. Duff, Answering for Crime: Responsibility and Liability in the Criminal Law (2007), at 87. This proposition, however, has one difficulty: how do we

State Energy Cartels J.W. Coleman, ‘State Energy Cartels’, 42(6) Cardozo Law Review 2233 (2020).

J.W. Coleman, ‘State Energy Cartels’, 42(6) Cardozo Law Review 2233 (2020). identify if a certain activity is considered deviant enough by the entire society to be deserving of criminal sanctions? With some activities such as murder or theft, which are so shocking that almost the entire society considers them deviant, it is easy to find an answer. The source of such shock lies not in morality but in the fact that such activities have visible victims.63x R. Nozick, Anarchy, State and Utopia (1974), at 65-71. No society faces trouble raising the consensus to criminalise such activities.

Such a straightforward analysis may not, however, be possible for activities which do not have a visible victim or are victimless – like cartelisation. These activities do not generally shock the entire society. For instance, we do not criminalise public smoking even though we are aware of the huge social costs they impose on society, as the moral shock is absent. Thus, normative justification of criminalisation requires harm, but it also needs something more than that. Two things can be highlighted in this regard: first, actual public opinion; and second, an abstract element of injustice.

The second element was highlighted by JS Mill when he argued that a society feels compelled to criminalise a harm only when, ‘means of success have been employed which is contrary to the general interest to permit – namely fraud or treachery, and force’.64x J.S. Mill, On Liberty (1859), at 179. This abstract element was also highlighted by Rawls in his ‘veil of ignorance.’ He used a hypothetical ‘veil of ignorance’ to identify what restrictions would generally be accepted by most humans in a given society, in a hypothetical pre-moral position if we were to be ignorant of the situations of our socio-economic existence.65x J. Rawls, A Theory of Justice (1999). According to this, an activity would deserve criminal sanctions if it were not just harmful but also unjust and fraudulent. Using the understanding espoused by these two theories as the backdrop, this section proffers three arguments: first, cartels cause harm; second, there is sufficient public disapproval to criminalise it; and third, cartel activities involve an element of injustice and fraud.4.1 Cartels Cause Harm

Cartels impose outsized costs on society. These costs are much larger than what we can ever recover from the responsible firms.66x G.J. Werden and M.J. Simon, ‘Why Price Fixers Should Go to Prison’, 57 Antitrust Bulletin 569, at 577 (1987); P. Buccirossi and G. Spagnolo, ‘Corporate Governance and Collusive Behaviour’, CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP6349 2007.

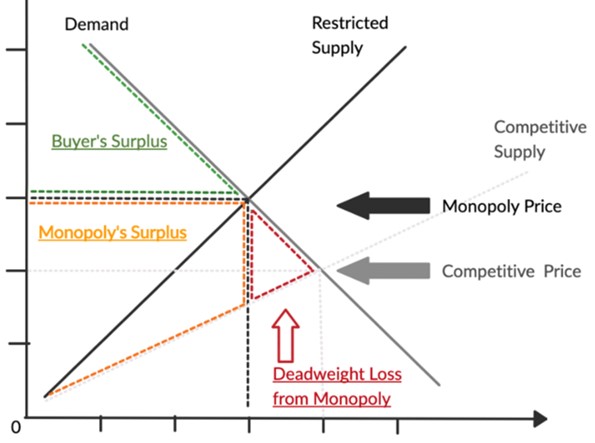

Cartels cause immense loss of welfare to the broader society. In simple terms, cartelisation is an attempt to raise the market prices to monopoly levels, away from competitive levels, even as oligopolistic number of firms exist. As can be observed in Figure 3, this helps transfer wealth from the consumers (and at times, from the government) to the cartelising firms. However, when this transfer takes place, deadweight loss is generated, which is a cost borne by society at large.67x G. Symeonidis, ‘Profitability and Welfare: Theory and Evidence’, 145 Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 530 (2018). In economic terms, this is the cost of foregone consumption by consumers. It also includes two other costs. One is the cost of maintaining the cartel and coordinating its organisation.68x M. Schiffbauer and S. Ospina, ‘Competition and Firm Productivity’, International Monetary Fund Working Papers 10/67 2010. The other cost is that of the loss to dynamic efficiency of the cartelised industry.69x P. Aghion et al., ‘Competition and Innovation: An Inverted-U Relationship’, 120(2) Quarterly Journal of Economics 701 (2005). After all, if the firms are able to cartelise and increase their income without being subjected to competitive forces, they are very likely to spend less on innovation and research, and dynamic improvement of their competitive abilities. These three costs taken together represent wasted resources that could have been used efficiently.

In reality, however, this deadweight loss is much larger because of the scarce resources a society has. This scarce resource has to be allocated to various economic activities and cartels distort this allocation, leading to an allocative inefficiency.70x A.C. Harberger, ‘Monopoly and Resource Allocation’, 44(2) American Economic Review 77 (1954); H. Leibenstein, ‘Allocative Efficiency and X-Efficiency’, 56 American Economic Review 392 (1966). When prices of a certain product increase, the society has to forego the consumption not only of that product but also of other products. This is especially true if the product which is subject to cartel prices is essential or has limited price elasticity. In that case, it is impossible to forego its consumption, distorting resource allocation in a significant way. A case of note is that of the European Truck Cartel which, over 14 years, worked to increase the prices of trucks which is the very basis of road transport industry and the demand for which is not very elastic. This cartel ended up distorting the entire economy by increasing the cost of commercial transport and limiting the resources available to invest in other productive sectors. As per one study, it caused allocative and deadweight losses to the tune of 15.5 billion Euros, this is in addition to the additional profits the firms must have earned through the overcharge.71x C. Beyer, K.V. Blanckenburg & E. Kottmann, ‘The Welfare Implications of the European Trucks Cartel’, 55 Intereconomics 120 (2020). The fines on the other hand amounted to 2.93 billion Euros.72x European Commission, ‘Antitrust: Commission Fines Truck Producers € 2.93 Billion for Participating in a Cartel’ (19 July 2016), https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/ro/IP_16_2582 (last visited 17 November 2022). While private damage claims are still being made in the courts, they are unlikely to account for the entire welfare loss suffered by society. And this is a case entailing the biggest fine ever imposed by the Commission on a cartel. In other cases, the gap between fines and damages imposed and welfare loss caused maybe even bigger.

Furthermore, it is not just that we are unable to impose enough fines on cartels to cover the net welfare loss, but fines do not even neutralise the profits earned by cartels as a totality. While some of the top cartels like the Truck Cartel had overcharges of approximately 10%,73x Cartel Damage Claims, ‘Trucks’, https://carteldamageclaims.com/cases/on-going-cases/ (last visited 17 November 2022). most cartels have much larger overcharges. Two sample cases are that of the global citric acid cartel and the global graphite electrode cartel, both fined by the EC in 2001.74x OECD, above n. 1. The first, as per the OECD, ‘raised the prices by as much as 30% and collected overcharges estimated at almost $1.5 billion’; and the second, ‘raised the price of graphite electrodes 50% in various markets, and extracted monopoly profits on an estimated $7 billion in world-wide sales.’75x Id. Was the Commission able to get this extra profits back in the form of fine? The citric cartel paid a fine of merely 135 million Euros and the electrode cartel a fine of 218.8 million Euros.76x EU Fines Price-Fixing Citric Acid Cartel, Food Navigator (18 July 2008), www.foodnavigator.com/Article/2001/12/06/EU-fines-price-fixing-citric-acid-cartel (last visited 17 November 2022); European Commission, ‘Commission Fines Eight Companies in Graphite Electrode Cartel’ (18 July 2001), https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_01_1010 (last visited 17 November 2022). These fines in no way recover the estimated profits that these firms were able to earn.

If we were to extend this discussion and look not just at individual cartel profits, but profits of all the cartels as a whole, they are going to be much larger. Most studies put the detection rate of cartels at approximately 15-25%. In the context of the EU, Combe, Monnier and Legal estimated the rate of detection to be between 12.9 and 13.3%.77x Combe and Monnier, above n. 54. In the American context, Bryant and Eckard estimated the probability of detection to be between 13 and 17%.78x P.G. Bryant and E.W. Eckard, ‘Price Fixing: The Probability of Getting Caught’, 73(3) Review of Economics and Statistics 531, at 536 (1991). Ginsburg & Wright estimate the detection rate to be around 25% in both the EU and the US.79x D. Ginsburg and J. Wright, ‘Antitrust Sanctions’, George Mason University Law and Economics Research Paper Series 6(2) 2010. Assuming that around one-fourth of all the cartels are detected and that the Commission is barely able to fine these cartels around 50% of the additional profits they earned, cartels as a whole are able to get away with seven-eighths of the additional profits they earn.

Connor and Lande have estimated that cartels overcharge anywhere between 28 and 54%.80x J. Connor and R. Lande, ‘How High Do Cartels Raise Prices?’, 80 Tulane Law Review 513 (2005); J. Connor, ‘Overcharges: Legal and Economic Evidence’, 22 Research in Law and Economics 59 (2007). Smuda, on the other hand, presented a more conservative mean of 20.7%.81x Combe and Monnier, above n. 54. Combe and Monnier agree with a similar rate of 20% overcharge.82x F. Smuda, ‘Cartel Overcharges and the Deterrent Effect of EU Competition Law’, 10(1) Journal of Competition Law and Economics 63 (2014). Going with the conservative estimate of 20%, it can be claimed that cartels as a whole make the society pay approximately 17.5% extra for the goods and services offered by cartelised industries.83x 17.5% is derived by multiplying 20% overcharge with 7/8 probability that they would get to keep the overcharge. This is a rather big number and causes incalculable harm to the society at large. A lot of everyday people have less money than they would, each time they engage with one of the cartelised firms. This is not very different from being defrauded at the hands of a multilevel marketing scheme or a securities fraud. This harm, however, is victimless, and thus, may not appear as shocking as someone being murdered or someone being defrauded. It does not result in consequences like people losing their life deposits due to a security fraudster, and hence, does not easily fall in the bracket of criminal activities. But does the general public agree with such an assessment? Or do they see cartel activities as akin to other categories of crime?4.2 Public Opinion

The second limb of the normative justification is to show that there is sufficient public resentment against cartel activities to justify their criminalisation. After all, it is what the society at large thinks of an activity which provides a basis for its criminalisation, even if such an assessment may not always be correct (e.g. criminalisation of homosexuality, marijuana consumption, and refugee influx).84x H.M. Hart, ‘The Aims of the Criminal Law’, 23 Law & Contemporary Problems 401 (1958); J. Hall, Principles of Criminal Law (1947), at 157. While the number of surveys is limited in number, a major study conducted by the US-based Centre for Competition Policy in 2014 studied public opinion in four jurisdictions: the US, Germany, the UK and Italy.85x A. Stephan, ‘Survey of Public Attitudes to Price Fixing in the UK, Germany, Italy and the USA’, Centre for Competition Policy Working Paper No. 15-8 2015. It found that a large majority of the public across these four jurisdictions agreed with the following assessments: first, they agreed that secretive collusion by cartelists has a negative consequence on consumers by leading to increased prices; second, they opined that secretive price-fixing was immoral, dishonest and criminal; third, they were of the understanding that price-fixing practices are widespread across business sectors; fourth, they agreed that cartel activities must be punished in some form; and fifth, individuals involved in price-fixing deserve some form of criminal punishment.86x Id.

The more or less consistent results across the four countries were shocking as they are different stages of criminalising cartels: while the US has done so for a century, the UK is still attempting to effectively criminalise, and Germany and Italy do not criminalise general cartel activities. For example, a question on whether cartelisation is more or as serious an offence compared to pure criminal fraud or theft. Across the four jurisdictions, over 90% of the people agreed with this statement.87x Stephan, above n. 88. The only explanation may be an instinctive human thought process and social conditioning, which identifies dishonesty and deception as major delinquency. Another study which was conducted in the Netherlands, also found that cartel activities were seen as serious offences by the Dutch public. Most of them were aware that cartels are illegal, considered them to be immoral and agreed that they have a negative effect on social welfare.88x P.T. Dijkstra and L. van Stekelenburg, ‘Public Attitude in the Netherlands towards Cartels in Comparison to Other Economic Infringements’, 17(3) Journal of Competition Law & Economics 620 (2021). Based on these studies, it is safe to assume that public opinion favours some form of criminal sanctions for cartelists. However, further sociological research in this regard may be required to concretise this claim. In any case, our normative argument has a third and stronger pillar to stand on: that cartels are vehicles of injustice in our market-based societies.4.3 The Abstract Element: Are Cartels Unjust?

Posner has argued that we cannot allow abstract moral reasoning to draft antitrust laws. According to him, it would lead to antitrust’s collapse into, ‘a weak field, a field in disarray, a field in which consensus is impossible to achieve in our society’.89x R.A. Posner, ‘Law and Economics is Moral’, 24 Valparaiso University Law Review 163 (1990). However, criminalisation cannot be based simply on law and economics, it has to be complemented with moral reasoning. As per Simester and Von Hirsch, criminal law ‘speaks with a moral voice’.90x A.P. Simester and A. von Hirsch, Crimes, Harms, and Wrongs: On the Principles of Criminalization (2011). This section would show that significant injustice is meted out by cartel activities and they carry an extraordinary level of dishonesty. Influence is drawn from the moral limits to criminal law as can be gleaned from the works of Mill and Rawls, as mentioned earlier, and of Feinberg, who has displayed that only those harms which affect our most fundamental interests are chargeable with criminal law’s coercive powers.91x J. Feinberg, Harm to Others (1984), at 11; Also see, J. Feinberg, Offense to Others (1985). While it may be argued that non-criminal institutional remedies can help protect the interests subverted by cartel activities, this article shall present arguments to the contrary. This section has two bases: first, cartel activities are inherently deceptive and fraudulent; and second, cartel activities affect the most fundamental element of our society: the free market.

4.3.1 Cartels are Inherently Deceptive and Fraudulent in Nature

This is what most people surveyed in the studies mentioned in Section 4.2 believe. That is a reasonable public opinion because usually the cartel offence arises out of an urge to steal, deceive and cheat. As Blackstone noted in his commentary, ‘an unlawful act is consequent upon such vicious will.’92x F.B. Sayre, ‘Public Welfare Offenses’, 33 Columbia Law Review 55 (1933). Scholars identify two constituents to inherent wrongfulness of an activity: culpability and the nature of the activity.93x N. Abrams, ‘Criminal Liability of Corporate Officers for Strict Liability Offenses ― A Comment on Dotterweich and Park’, 28 UCLA Law Review 463 (1981). Culpability refers to the degree to which the perpetrator is delinquent and their state of mind when they committed the questionable actions. Nature of the activity refers to the immoral content of the activity itself and if on its own it is dishonourable.

On culpability of the individuals involved, there is no doubt that those engaging in cartels are not gullible or uninformed individuals. They are not tricked or coerced into taking part in elaborate negotiations, brainstorming the numbers, implementing an organisation-wide pricing policy, and swearing into an oath of secrecy.94x OECD, above n. 1, at 15; OECD, Fighting Hard Core Cartels: Harm, Effective Sanctions and Leniency Programmes (2002), at 8 [which noted cartel members’ efforts to keep their activities secret, their burning bid files in bonfires and hiding computer files in the eaves of one employee’s grandmother’s house]. They are more often than not highly paid and well-advised individuals with a choice not to engage in an activity that causes society-wide harm. The presence of intent, free will to steal and cause harm makes those engaging in cartel activities culpable. A host of similar activities, whether it is securities fraud or embezzlement or bribery, are all criminalised and there is little evidence that cartel conspiracies are any different. In fact, there is ample evidence from many cartel prosecutions that cartelists go through significant troubles to devise sinister schemes to avoid detection and disrupt potential investigations.95x C. Harding and J. Edwards, Cartel Criminality: The Mythology and Pathology of Business Collusion (2015), at 20. Strategies such as hiring cryptographers and experts to advise on undetectable price-fixing or bid-rigging designs are common.96x M.B. Clinard and R. Quinney, Criminal Behavior Systems (1967). Thus, it can be said that there is sufficient culpability of the actors of a cartel scheme.

Coming to the nature of the activity itself, some have argued that cartelisation is nothing more than ‘aggressive business behavior.’97x S.H. Kadish, ‘Some Observations on the Use of Criminal Sanctions in Enforcing Economic Regulations’, 30 University of Chicago Law Review 423 (1963) Kadish argues that the nature of cartel activities lacks the immoral content which core crimes carry. It is not akin to theft as the victims are not subjected to a feeling of having lost their possessions. It is not similar to robbery as there is no use of force. Unlike most crimes, there is no invasion into bodily privacy or physical safety.98x Id. However, the deficit in these arguments is that the ambit of core crimes is broader than those where the victims are a subject of mental or physical trauma. Since the industrial revolution, almost all societies have deemed it just to criminalise many victimless crimes which have broad welfare consequences.99x K.A. Swanson, ‘Mens Rea Alive and Well: Limiting Public Welfare Offenses–In re C.R.M.’, 28 William Mitchell Law Review 1265 (2002); A. Leavens, ‘Beyond Blame – Mens Rea and Regulatory Crime’, 46 University of Louisville Law Review 1 (2007).

The most recent welfare crime, still in evolution, is the environmental crime.100x ‘The EU Steps Nearer to Tougher Regime to Fight Environmental Crime’, Osborne Clarke (11 January 2022), www.osborneclarke.com/insights/eu-steps-nearer-tougher-regime-fight-environmental-crime (last visited 17 November 2022). The Commission has already submitted a proposal on ‘the protection of the environment through criminal law and replacing Directive 2008/99/EC’ to the European Parliament.101x European Commission, ‘Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Protection of the Environment through Criminal Law and Replacing Directive 2008/99/EC’ (2021/0422). There is no immediate victim of manipulating the emissions of vehicles you make or of causing deforestation in a region. But we still deem the negative effects of these practices on society to be high enough to make them immoral and criminal.102x M.G. Faure and G. Heine, Criminal Penalties in EU Member States’ Environmental Law (2022). In fact, most corporate practices affecting the environment are done with the same pursuit as those for cartel activities: bigger profits. Thus, this article proffers that the nature of the proposed cartel offence is similar to other welfare crimes already on the statute books. By transferring wealth, leaving a lot of people poorer, reducing consumption opportunities, disturbing resource allocation in the economy, harming honest businesses, promoting a corporate culture where conspiracies are rewarded, abusing state resources, creating unfair rules in the market, and most importantly, by intently deceiving the general public, the nature of the cartel offence is inherently immoral, unjust and deserves our social disapproval.4.3.2 Cartel Activities Affect the Most Fundamental Element of Our Society: Free Market

While in the economic analysis of law, criminalisation is often thought of as a tool to create deterrence, the apparent purpose of criminalisation is much larger. Criminal justice systems in modern society are meant ‘to apply the rule of law as a means of providing social stability’.103x R.D. Hunter and M.L. Dantzker, Crime and Criminality: Causes and Consequences (2012), at 13. Social stability is what concerns most people when they think of crimes. This stability is specific to each society and its physical, temporal and moral situation. Social stability in post-industrial societies, as per Hayek, is a result of market competition and network coordination.104x J. Birner and R. Ege, ‘Two Views on Social Stability: An Unsettled Question’, 58(4) American Journal of Economics and Sociology 749 (1999). Durkheim too argued that social cohesion and cooperation are a result of the division of labour and the presence of market forces.105x E. Durkheim, The Division of Labour in Society (1893). Adam Smith’s indivisible hand also refers to market forces as the primary tool of social organisation today.106x E. Rothschild, ‘Adam Smith and the Invisible Hand’, 84(2) American Economic Review 319 (1994). As Ross theorised in 1907, a variety of economic sins were bound to emerge in post-industrial society and would have to be treated with the same attitude as we dealt with physical harm.107x E.A. Ross, Sin and Society: An Analysis of Latter-Day Inequity (1907). Taken together, the work of these theorists supports a claim that the market and its competitive forces are essential to our social stability and any attempt to subvert them should be treated with utmost reaction.

However, competitive markets are not just essential from a sociological point of view. From the perspective of justice and fairness, too, they are important as they are an essential redistributive mechanism. Free markets, by creating opportunities, providing choice and creating competitive prices ensure that people can exchange their intellect, resources and abilities at the best possible prices. Looking at it through Rawls ‘Veil of Ignorance’ one could pose a question as to whether one would want to be on the losing side (whether as a consumer or a firm not participating in the cartel) if the market is unfair and uncompetitive. The obvious answer would be that every person behind this veil would support the protection of the voluntary nature of the transaction, unadulterated by price-fixing practices. The free market ensures, to a certain extent, this goal of attaining equality. Cartels affect this fundamental element of our social stability by creating hidden rules and in the process hurt the process of ensuring fairness and justice. This provides a very strong normative justification for their criminalisation. -

5 The Limitations of Corporate Fines

That fines have not been deterrent enough has already been displayed in Section 3. In this section, the article shall assert that corporate fines have certain inherent limitations as a deterrence function. It shall also propose that a combination of fines and criminal sanctions would provide the best possible deterrence effect. These arguments shall have three components: first, corporate fines do not target the actual wrongdoers; second, to achieve optimality, fines would have to be much larger than they currently are and reach a socially undesirable level; third, criminal sanctions will add an incalculable value to deterrence and limit the need to enlarge fines to socially undesirable levels.

5.1 Fines and Skewed Corporate Governance: An Agency Problem

The current enforcement model of progressive fines does not take into account the issue of inferior corporate governance.108x Buccirossi and Spagnolo, above n. 68. Most corporations are managed by a set of executives who are agents of the shareholders, the actual owners. While elaborate rules on corporate governance are in place, the presence of the agency problem is widespread and corporate governance issues are common.109x F. Thépot, The Interaction Between Competition Law and Corporate Governance – Opening the ‘Black Box’ (2019). As Clarke has shown, corporate governance rules are essentially cyclical and misplaced incentives due to self-interest of the agents find one way or the other to creep into the governance institutions.110x T. Clarke, ‘Cycles of Crisis and Regulation: The Enduring Agency and Stewardship Problems of Corporate Governance’, 12(2) Corporate Governance 153 (2004). Power is inherently asymmetric in bureaucratic contexts and the same is true for corporate enterprises.111x D. Band, ‘Corporate Governance: Why Agency Theory is Not Enough’, 10(4) European Management Journal 453, at 459 (1992). This gives rise to moral hazards as there might be sufficient motivation for the agents to resort to anti-competitive practices, even though they might be aware that if detected it may impose costs on the firm and the owners.112x C. Argenton and E.E.C. van Damme, ‘Optimal Deterrence of Illegal Behavior Under Imperfect Corporate Governance’, TILEC Discussion Paper No. 53 2014. These may be the result of managerial incentive schemes like annual profit-related bonuses or economic cycles, as there may be an incentive during economic downturns to engage in cartels to improve the baseline.113x Cseres, Schinkel & Vogelaar, above n. 12. There is also a possibility of corporate corruption by way of personal kickbacks for taking part in cartels.114x A. Stephan, ‘Cartel Laws Undermined: Corruption, Social Norms, and Collectivist Business Cultures’, 37(2) Journal of Law and Society 345 (2010).

The true perpetrators of cartel activities thus are the managers who do not usually own the company or own a minuscule part of it. Of all the listed companies in the world, only 7% of the shareholding belongs to strategic individuals and corporate executives.115x OECD, Owners of the Worlds Listed Companies (2019), at 11. They, however, have an overwhelming majority of the decision-making power. Their practices may often escape the monitoring mechanisms. In such a scenario, simply relying on corporate fines is inappropriate as it sanctions the owner-shareholders, not the managers. This is becoming especially problematic due to increasing public shareholding of corporations.

Today, 56% of the shareholding in all publicly listed companies the world over is owned by institutional investors (incl. pensions funds, mutual funds, insurance companies etc.) and governments, which are indirectly funded by the general public.116x Id. Another 27% is directly owned by retail investors and other free-floats.117x OECD, above n. 118. Thus, any fine imposed on corporations, if it is optimal, is indirectly a fine on the general public owners but for the fault of their agents. This does not allow for the sanction to be internalised by the actual doers, limiting its deterrence effect.118x Argenton and Damme, above n. 115. What makes the problem worse is that voting power in most corporations is concentrated in the hands of promoters and founders, with spread-out retail and minority investors having limited control over company affairs.119x D. Leech, ‘Shareholder Voting Power and Corporate Governance: A Study of Large British Companies’, 27(1) Nordic Journal of Political Economy 33 (2001). This problem is also aggravated by the fact that corporations have limited ability to punish executives.120x R.H. Lande and J.M. Connor, ‘Cartels as Rational Business Strategy: Crime Pays’, 34 Cardozo Law Review 427 (2012). These individuals are often protected with the help of elaborate contracts, wherein not only is dismissal difficult but also comes with high costs to the corporation. While the shareholders may take punitive or preventive action against the management in the form of shareholders litigation seeking damages or by firing the management. However, shareholder damage suits continue to remain a rarity in Europe and have found limited success.121x K. Hopt, ‘Modern Company Law Problems: A European Perspective Keynote Speech’, OECD (2001); M. Gelter, ‘Why Do Shareholder Derivative Suits Remain Rare in Continental Europe?’, 37 Brooklyn Journal of International Law 843 (2012). This is due to entrenched executive power and interconnected power relations.5.2 Truly Optimal Fines Would Be Socially Undesirable

Optimality of fine refers to a state when each additional euro of fine results in more than a euro worth of benefit for the society at large.

Global Cartel Enforcement Report 2021, Morgan Lewis, www.morganlewis.com/pubs/2022/01/global-cartel-enforcement-report-2021 (last visited 17 November 2022).

This means that fines would be optimal only when the expected punishment can completely neutralise the expected gain.122x K. Yeung, ‘Quantifying Regulatory Penalties: Australian Competition Law Penalties in Perspective’, 23 Melbourne University Law Review 440 (1999). Since the expected punishment is the cost of sanction multiplied by the probability of getting caught, the actual cost of sanction must be equal to expected gain divided by the probability of getting caught.123x Whelan, above n. 27.

To illustrate,

Expected gain: 100 Euros

Expected cost of punishment (if the probability of getting caught is ¼): Sanction * 1/4.

Sanction is optimal when

Sanction × ¼ = 100 Euros = Sanction = 100 × 4 = 400 Euros.While it is impossible to measure the exact gain an average cartel makes and the probability of their detection, various scholars have made an attempt to measure it. As per Wils, the expected gains of a cartel are around 20% of their actual mark-up over the course of 5 years, which is equivalent to 50% of their annual turnover; and the probability of detection has an upper limit of 33%.124x W. Wils, ‘Is Criminalization of EU Competition Law the Answer?’, in K.J. Cseres, M.P. Schinkel & F.O.W. Vogelaar (eds.), Criminalization of Competition Law Enforcement (2006) 60. According to this calculation, optimal fines should be somewhere around 150% of annual turnover. As per Werden, the probability of detection is around 25%, thus increasing the optimal fines to 200% of annual turnover.125x G. Werden, ‘Sanctioning Cartel Activity: Let the Punishment Fit the Crime’, 5(1) European Competition Journal 19, at 24 (2009). As has already been displayed in Section 4.1, detection rates were pegged at 15-25% by most studies. Thus, it can be concluded that an optimal fine would be equal to 200% of annual turnover: an exorbitantly large and undesirable amount of fine. Already the current cap of 10% of annual turnover is seen by many as unreasonable.126x Jones and Harrison, above n. 19. Further, there are concerns about many productive companies heading to bankruptcy because of enlarging fines.127x B. Wardhaugh, Cartels, Markets and Crime: A Normative Justification for the Criminalisation of Economic Collusion (2013), at 95-100. It is one of the key reasons behind capping fines at the level of 10% of the turnover or lower, which is not enough to deter cartel activities.

5.3 Criminal Sanctions Will Help Cap Fines at Socially-Desirable Levels

As can be observed in Figure 4, the fines in the EU are already leaving behind the rest of the world by a huge margin and are constantly rising. They are, as this section has shown, of limited versatility. Even though Becker’s modelling would show that fines can indefinitely be raised, our socio-economic realities and need for stability require that the fines should have a reasonable limit.128x P. Buccirossi and G. Spagnolo, ‘Optimal Fines in the Era of Whistleblowers – Should Price Fixers Still Go to Prison?’, in V. Ghosal and J. Stennek (eds.), The Political Economy of Antitrust (2007) 81, at 107-8. This reasonable limit may not be enough to deter, given that the expected benefits of cartelising are much higher and also because the source of the implicated activities (executive-agents) and the landing of the fine’s impact (shareholder-owners) do not overlap. In such a scenario, complementing fines with criminal sanctions would allow us to significantly improve the deterrence effect of the cartel enforcement system in the EU.

While an argument may be presented that deterrence can also be created by using personal administrative sanctions against the executives, instead of criminal sanctions, there are two obstacles to this argument. First, as mentioned earlier, the deterrence effect of criminal sanctions is indefinite, whereas administrative fines are easy to handle for highly placed executives. This is especially true when they have the security of director and officer’s insurance.129x N.R. Mansfield, J.T.A. Gabel, K.A. McCullough & S.G. Fier, ‘The Shocking Impact of Corporate Scandal on Directors’ and Officers’ Liability’, 20 University of Miami Business Law Review 211 (2012). Second, fines on executives too would have to be prohibitively high for it to be effective, when they may be adequately compensated for any fine by favourable employment contracts.130x P. Henning, ‘Why It is Getting Harder to Prosecute Executives for Corporate Misconduct’, Columbia Law School Blue Sky Blog (13 June 2017), https://clsbluesky.law.columbia.edu/2017/06/13/why-it-is-getting-harder-to-prosecute-executives-for-corporate-misconduct/ (last visited 17 November 2022); J. Stewart, ‘In Corporate Crimes, Individual Accountability is Elusive’, The New York Times (9 February 2015), www.nytimes.com/2015/02/20/business/in-corporate-crimes-individual-accountability-is-elusive.html (last visited 17 November 2022). As such, fines alone may not be sufficient.

Criminal sanctions, as has been noted many times, have incalculable costs for most white-collared individuals. They entail costly restrictions on liberty, have reputational costs and significantly affect career prospects. This means that the cost of the punishment increases much beyond just the economic costs and creates a strong deterrence effect. In addition, criminal sanctions on the ‘directing minds and will’ who got the company into a cartel will ensure that the crime and punishment are congruent: the one who commits it is the one who is punished. This, on its own, will improve deterrence. Further, as displayed in Section 3, the US is already having a slowdown in cartel activities due to its penal sanctions. As per one study of antitrust practitioners amidst the US executives, the threat of imprisonment and criminal sanctions had the biggest deterrent effect on their clients. Fines, in fact, were the third main instrument, preceded by the threat of private damage suits. These facts, taken together, show that criminal sanctions make for an ideal tool to use and mere reliance on fines is not ideal. -

6 The Challenge of Criminalisation: Laying Down Some Principles

Whenever a strong policy proposal is made, it is pertinent to follow the principle of Occam’s Razor; that is to say, we should use state power to restrict liberties only to the extent it is necessary, and in accordance with basic rule of law principles. If the restraints are too arduous, extreme and commonplace, it is very likely that good executives would avoid working within the EU and management quality may downgrade. Three principles can be highlighted with respect to criminalisation of cartel enforcement.

First, that cartel crimes should not have an omnibus definition. Four different types of cartel activities can be identified and must be differentiated in how they are sanctioned:131x Norris v. Government of the United States, [2010] UKSC 9. first, where the customer is duly informed about a price-fixing agreement. In such a case there is no crime because the intent to deceive is absent and there is no element of secrecy.132x For e.g., the ‘Customer Notification’ exclusion in the UK law at Sec. 30, Enterprise Act (2002). Second, where there is complete secrecy and a price-fixing agreement is carried out with mutual consent between various competitors. This certainly qualifies as a ‘hardcore cartel’ and those involved in negotiating the agreement deserve criminal sanctions of varying levels as per their role in the scheme. Third, where some of the competitors were forced to join the cartel through the use of force, coercion or fraud. In this case, while the officials of the victimised company are free of any liability, the rest of the individuals have committed an even graver crime and deserve a higher degree of punishment. Fourth, one where a party was aware of the cartelisation but did not report it to the authorities.133x Swaine, above n. 22. Any attempt at criminalisation must be cognizant of the various cartel activities and accordingly create distinct categories of cartel crimes.

Second, criminalisation should have a strong basis in procedural fairness and cannot be implemented by the Commission. The Commission, given its administrative nature, lacks separation of powers.134x B. Ganglmair and A. Günster, ‘Separation of Powers: The Case of Antitrust’, SSRN Electronic Journal 3, 17 (2011). It has legislative powers, investigative powers and adjudicatory powers. This is not a particular problem with civil fines, but when it comes to criminal sanctions, a strict separation of powers in these three types of functions is important to ensure due process and justice.135x C. Teleki, Due Process and Fair Trial in EU Competition Law (2021), at 1-26. Thus, any attempt at criminalisation at the EU-wide level has to necessarily start at national levels, in accordance with due process and human rights standards.136x Whelan, above n. 6, at 34-40. This would be compliant with the Lisbon Treaty, which to a great extent nationalised criminal enforcement measures.137x P. Csonka and O. Landwehr, ‘10 Years after Lisbon – How “Lisbonised” is the Substantive Criminal Law in the EU?’, 4 EUCrim 261 (2019). The two processes of civil and criminal investigations may run parallelly but should be independent of each other.

One may argue that this leads to ‘double jeopardy’ since the same activity is being punished twice: once, an administrative penalty in the form of a fine; and second, a criminal penalty under national criminal laws. This is an important issue since it goes to the very root of due process and implicates Article 50 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (CFREU), which protects against double jeopardy. The ECJ rendered a clear position on this matter this year in its simultaneous judgements in bpost SA v. Commission138x Case C-117/20 (2022). and Bundeswettbewerbsbehörde v. Nordzucker.139x Case C-151/20 (2022). It agreed that administrative actions under competition laws are covered under double jeopardy. However, it went on to hold that parallel proceedings under different legislations, having distinct but complementary objectives and processes, do not violate double jeopardy.140x Case C-117/20, bPost SA v. Commission, [2022] at 53-6; Case C-151/20, Bundeswettbewerbsbehörde v. Nordzucker, [2022] at 50-7. Thus, a distinct, parallel and complementary proceeding under national criminal legislations would not give rise to the problem of double jeopardy.

Third, parallel investigations must have a mutually linked leniency programme. As has already been witnessed, the lack of a common leniency programme for private damages and public fines has reduced the number of leniency applications.141x See Section 2 of the article. A similar outcome would result if leniency applicants do not get respite from criminal sanctions in addition to civil fines. This would plummet detection rates significantly since almost two-thirds of the cartels are detected through leniency applications.142x Friederiszick and Maier-Rigaud, above n. 50. This is undesirable from a deterrence perspective, and hence, a leniency exception must be present in legislation criminalising cartel crimes. -

7 Conclusion and Some Afterthoughts

There is no doubt that criminalisation is a double-edged sword. Every time we criminalise an activity we impinge on individual liberty and take a step closer to a police state. As Dr. Ferris in Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged observed, ‘when one declares so many things to be a crime that it becomes impossible for men to live without breaking laws.’143x A. Rand, Atlas Shrugged (1957), at 411. This is not the proposal of this article. Overcriminalisation comes with many costs for society, whether it is the cost of maintaining prisons, creating costly investigative agencies or the mental cost to individuals at risk of wrongful sanctions.144x E. Luna, ‘The Overcriminalization Phenomenon’, 54 American University Law Review 703, at 719-39 (2005). In some societies, where democracies are non-functional and police power lacks due procedure, a criminal sanction for cartels cannot be normatively justified for the risk of wrongful prosecution would be too large.

That is not the case with the EU. The courts are a powerful and effective check on the executive power. Procedural rights are strong and human rights standards at the pan-EU level are highly progressive. In such a scenario, an activity which is imposing great harm on society, is challenging its very basis (of fair markets) and is morally unjust deserves to be duly punished. As has been displayed, fines alone have not sufficiently deterred cartel activities. A lot of planning and funds are being invested into creating effective and profitable cartel schemes. This must be stopped. Criminal sanctions, which are normatively justified for wilful and harmful activities like this, are the right tool. They would allow us to control the ever-rising fines which, as has been displayed in Section 5, are becoming socially undesirable by imposing high costs on shareholder-owners and not effectively sanctioning the executive-agents.

The article recognises that this is not going to be an easy endeavour. As can be gauged from the British experience, criminal sanctions are not easy to implement. In fact, some countries like Austria, which had criminal sanctions for cartels abolished it due to practical difficulties in implementation. Unlike the US, which has had cartel crimes since over a century and has the jurisprudence required to carry out due adjudication, European countries will face many legal and procedural obstacles. This becomes a bigger problem since criminalisation at the EU-wide level is only possible through individual country-level consensus. This is a tall order and is ridden with political challenges. However, practical difficulties have to be contented with when the question is about hundreds of billions of Euros (if not trillions) worth of harm to the public and the creation of an unequal market with unfair rules. ‘A crime is born in the gap between the morality of society and that of the individual,’ wrote the author Håkan Nesser.145x H. Nesser, Hour of the Wolf (1998). This article believes that such a gap exists in the case of cartel crimes. -

1 OECD, Hard Core Cartels (2000), at 5.

-

2 A. Stephan, ‘The Battle for Hearts and Minds: The Role of the Media in Treating Cartels as Criminal’, in C. Beaton-Wells and A. Ezrachi (eds.), Criminalising Cartels (2011) 111, at 129.

-

3 T.O. Barnett, ‘Criminal Enforcement of Antitrust Laws: The U.S. Model’, United States Department of Justice (2006), www.justice.gov/atr/speech/criminal-enforcement-antitrust-laws-us-model (last visited 17 November 2022).

-

4 Verizon Communications v. Law Offices of Curtis Trinko (2004) 124 S. Ct. 872.

-

5 OECD, above n. 1, at 5.

-

6 P. Whelan, The Criminalization of European Cartel Enforcement (2014), at 44-78.

-

7 Id., at 260-88.

-

8 E. Milton, ‘Putting the Price-Fixers in Prison: The Case for the Criminalisation of EC Competition Law’, 5 Hibernian Law Journal 159 (2005); D. Sokol, ‘Reinvigorating Criminal Antitrust?’, 60 William & Mary Law Review 1545 (2019).

-