-

1 Introduction

Better regulation – called bessere Rechtsetzung in Germany – has a long-standing history, not only in Germany but also in other countries. Those overall systems can be understood as systems of quality assurance of legal provisions, or, more broadly, of government decisions and policy measures. This article analyzes different features of the German system that represent some obstacles to making it a full quality assurance system. Without making a fully detailed investigation, the article looks at some selected, well-documented challenges and problematic issues of the German regulatory impact assessment scheme.

The systems of better regulation differ between countries and depend very much on the institutional design, characteristics, and organization of the country.1x See Andrea Renda, Impact Assessment in the EU: the state of the art and the art of the state, Centre for European Policy Studies (2006); Claudio M. Radaelli, Diffusion without convergence: how political context shapes the adoption of regulatory impact assessment, Journal of European public policy (2005); on the German system in international comparison see Werner Jann, Kai Wegrich & Jan Tiessen, Bürokratisierung und Bürokratieabbau im internationalen Vergleich – wo steht Deutschland? (2007). The evolution of better regulation systems depends on those characteristics and their specific contexts. This is also true of the development of Germany’s better regulation system, which has followed specific patterns and has become more and more sophisticated over time. These developments were partly in line with trends in other countries, particularly OECD countries.2x See OECD, Better Regulation in Europe: Germany 2010 (2010) and OECD, Regulatory Policy Outlook 2015 (2015). The understanding of the factors that represent “good regulation” has significantly evolved over time in line with major trends also observable in other countries. An important function of the systems is the legitimization of government decisions leading to government actions and policy measures implemented through laws and regulations. In a way, challenges and needs of societies change over time, and so does the meaning of what are legitimatized decisions and actions taken by governments.

The German system of better regulation shall be assessed from different angles. The article looks at some key factors for the appropriateness of a regulatory impact assessment system as a quality assurance system. The evidence presented draws on literature reviews, own observations, and some empirical results from a research project that focused on the implementation of federal legislations by subnational units.

The article is organized as follows: Section two outlines the assessment framework for a critical appraisal of Germany’s system. Section three summarizes the main elements of Germany’s better regulation system, namely its development path and its current structure, its main actors, and the areas of the regulatory impact assessment. In section four the challenges of Germany’s federal structure for the system are outlined. Section five appraises the system’s appropriateness as a quality assurance system. In particular, evidence will be provided on the practical consequences of Germany’s federal structure, the factual compliance with the rules and procedures of the better regulation system, and the compliance costs approach. Finally, the main conclusions are summarized in section six. -

2 Appraisal framework

Systems of better regulation have a number of versatile objectives. It is therefore important to have a clear and consistent definition of better regulation, as it is understood differently in individual contexts. The rationalization of the policy process, the control of bureaucracy and policy learning can be seen as the three main aims of better regulation.3x See Claudio M. Radaelli, Measuring policy learning: regulatory impact assessment in Europe, Journal of European Public Policy 16 (8), 1145-1164 (2009) and Claudio M. Radaelli & Fabrizio De Francesco, Regulatory impact assessment, political control and the regulatory state, 4th General Conference of the European Consortium for Political Research (2007). Systems of better regulation can be understood as a quality assurance system. They comprise administrative or procedural activities aimed at achieving legislative goals. One can refer to these systems as meta-regulation, which contain, in more or less formalized ways, a set of rules and procedures around the entire rule’s life.4x See Brownen Morgan, The Economization of Politics: Meta-Regulation as a Form of Nonjudicial Legality, 12 Social & Legal Studies, 489 (2003); Claudio M. Radaelli, Evidence-based policy and political control: what does regulatory impact assessment tell us? Paper for the European Consortium for Political Research Joints Sessions, workshop on “The Politics of Evidence-based Policy Making” (2008). These rules serve as a quality assurance system and are oriented towards traditional management or policy cycles. In this sense, the law or regulation as final product and its production process are subject to quality measures.5x See Ortlieb Fliedner, Moderner Staat – moderne Gesetzgebung? Sieben Thesen für bessere Gesetze (2004). In a broader and more comprehensive perspective – lawmaking as business model – the entire life of a rule/law including its implementation and execution can be considered.6x See Hermann Hill, Recht als Geschäftsmodell – Von Better Regulation zu New Regulation, Die öffentliche Verwaltung (DÖV), 809 (2007).

Better regulation comprises the avoidance of overregulation, maintaining a manageable number of legal substantive requirements, and improving the quality of legislation.7x See Bastian Jantz & Sylvia Veit, Entbürokratisierung und bessere Rechtsetzung, in Handbuch zur Verwaltungsreform, 126 (Bernhard Blanke, Franz Nullmeier, Christoph Reichard & Göttrik Wever, eds., 2011) and Kai Wegrich, Das Leitbild „Better Regulation": Ziele, Instrumente, Wirkungsweise (2011). The quality assurance of legislation does not end with the clarity of the norm, but involves the entire regulatory regime. It includes procedures such as monitoring, assessment, and optimization of the regulation, and, moreover, analytical methods and instruments as part of the rule-making.8x See Claudio M Radaelli & Anne C.M. Meuwese, Better regulation in Europe: Between Public Management and Regulatory Reform, 87 Public Administration, 639 (2009). These procedures and instruments can be applied before (i.e., ex ante) or after (i.e., ex post) adoption of a regulation. The toolkit of better regulation knows a number of instruments that can be applied to different phases of a rule’s life cycle. It contains various instruments such as regulatory impact assessments, consultations, systematic stakeholder involvement, measures to reduce administrative burdens and to simplify regulations and administrative procedures.9x Andrea Renda, Lorna Schrefler, Giacomo Luchetta & Roberto Zavatta, Assessing the Costs and Benefits of Regulation. Final Report, Study for the European Commission, Secretariat General (2013). Furthermore, it includes directives on the execution of laws, considerations of alternatives to traditional lawmaking, delimitation of laws (sunset regulation), politics of rule-making, and the review and evaluation of norms and legislation.

Over the last few decades, many states have established comprehensive systems and procedures to guarantee the quality of regulations. Systems of better regulation/regulatory impact assessment serve different functions. One function is to provide decision makers with a higher level of information (information function) to make better decisions.10x See Colin Kirkpatrick & David Parker (eds.), Regulatory Impact Assessment: Towards Better Regulation? (2007). In practice this can be achieved through stakeholder participation in the process of lawmaking, which increases the legitimacy of policy measures (legitimacy function). It is not only about stakeholder participation, but the production function of better regulation also aims at effectiveness, efficiency, compliance, practicability, sustainability and transparency of the legislation and its production process. This should lead to a rationalization of lawmaking and policymaking.11x See Gunnar Folkert Schuppert, Governance und Rechtsetzung. Grundfragen einer modernen Regelungswissenschaft (2010).

The German better regulation system has been investigated in a number of research studies and by international organizations, especially from the OECD.12x See OECD (note 4), but also Sylvia Veit, Bessere Gesetze durch Folgenabschätzung? Deutschland und Schweden im Vergleich (2010) and among others Werner Jann & Bastian Jantz, Bürokratiekostenmessung in Deutschland. Eine erste Bewertung des Programms "Bürokratieabbau und bessere Rechtsetzung" der Großen Koalition, in Zeitschrift für Gesetzgebung 1/2008, S. 51-68 This article focuses on the rationalization of the policy process from an economic point of view. For the appraisal of Germany’s better regulation system as a quality assurance system, three main factors for achieving better regulations are investigated: First, how the implementation and application of legislation by subnational units is taken into account in the better regulation system; second, it refers to the information the system provides for evidence-based and rational decisions on regulations and policies; and third, it looks at the approach and the indicators used to determine costs and benefits of regulations and thereby prove that the benefits outweigh the costs. To achieve this, a) the provisions of a better regulation system should be complied with, i.e., they should be followed by actors preparing legislative proposals, b) the system should take into account different possible implementation choices and discretionary power of subnational units, and c) it should provide information on costs but also on benefits of proposed regulations. These three factors chosen represent major challenges for the current system and have been at the center of attention in the recent past.

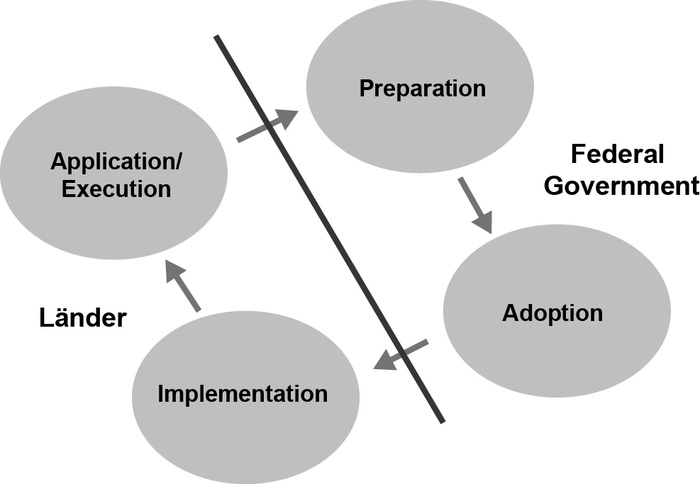

The implementation of a regulatory impact assessment system along a rule’s life has an impact on the performance of the system and its ability to guarantee regulatory quality. For the assessment of Germany’s better regulation system the entire rule’s life as a regulatory process with its phases of preparation, adoption, implementation, and application has to be taken into consideration, as well as the applied tools and foreseen instruments within this process. The system is investigated in terms of its adequacy to provide information for rational policy decisions from an economic viewpoint, i.e., effective and efficient regulations.

From this perspective, in Germany there are a number of issues that can be considered problematic. These refer in particular to the implications arising from the so-called executive federalism. Moreover, compliance with the rules set for the regulatory impact assessment has been a problem in the past, leaving the information for decision-making incomplete. Also, the exclusive focus on compliance costs to the neglect of the benefits of regulations leaves the decision maker and public an incomplete picture of the impact of a given regulatory proposal. -

3 Regulatory impact assessment at the federal level and the constitutional framework for the execution of federal legislation

When it was established, the German system of better regulation was targeted primarily at safeguarding accuracy and comprehensibility of laws, and at avoiding inconsistencies within the laws. Germany’s current system is the result of a number of changes and long-term evolution, which also reflect a changed understanding of what constitutes “good regulation” in the sense of high quality.

For a better understanding of the German regulatory impact assessment system, this section summarizes the major developments over the last few years (subsection 3.1) and provides a brief overview of the current systems’ characteristics, the systems’ actors, and the scope of the regulatory impact assessment (subsection 3.2).3.1 Cornerstones of the development of Germany’s regulatory impact assessment system

Until the year 2000 the impact assessment on the federal level was based on a variety of documents such as the Handbuch der Rechtsförmlichkeit (Handbook on formal requirements for drafting legislation)13x The handbook is available at: http://www.hdr.bmj.de. of the Federal Ministry of Justice (1991 and 1999), which contains rules on systematic and legal scrutiny. Furthermore, the handbook contained a number of questions and guidelines to ensure compliance with constitutional rules. Moreover, following a decision of the Federal Government, the so-called blaue Prüffragen (blue test questions), representing a checklist of 10 questions, has had to be taken into account when drafting a law since 1984.14x See OECD, Reviews of Regulatory Reform: Germany 2004. Consolidating Economic and Social Renewal 69 (2004). The Federal Ministers were held responsible for ensuring that legislative proposals were checked and verified according to the blue test questions as early as possible. Whereas the blue test questions, the handbook and several guidelines were tools for the preparation of legislation, some areas for the impact assessment of legislation (such as the budgetary impact of new regulations) were provided in the Gemeinsame Geschäftsordnung der Bundesministerien (GGO) (Joint Rules of Procedures of the Federal Ministries) before its major revision in 2000.

By the end of the 1990s the political agenda placed a greater emphasis on the efficiency of the public sector. At this time, the objective of better regulation also broadened out from a sole orientation towards deregulation and simplification towards a higher acceptance and stronger focus on the impact of legislation/regulations. The regulatory impact assessment became the core of the reform efforts. The revision of the GGO in 2000 introduced and institutionalized the regulatory impact assessment. At that time, the guideline on regulatory impact assessment15x Bundesministerium des Innern (ed.) Leitfaden zur Gesetzesfolgenabschätzung (2000). and the handbook on regulatory impact assessment16x Carl Böhret & Götz Konzendorf, Handbuch Gesetzesfolgenabschätzung (GFA), Gesetze, Verordnungen, Verwaltungsvorschriften (2001). were developed on the request of the Federal Ministry for the Interior. In the years that followed, “better regulation” in Germany has been primarily related to the reduction of bureaucracy costs. The driving force of this development was the introduction of the fast-spreading standard cost model in a number of European countries. This development also led Germany to extend the regulatory impact assessment to bureaucracy costs (2006), based on the standard cost model followed by the adoption of the broader concept of compliance costs (2011). In 2009, sustainability also became an area of the impact assessment. A game changer was the establishment of the NRCC in 2006, along with the revision of its mandate in 2011, which significantly changed the overall governance in the area of better regulation.

In the recent past the Federal Government took a number of decisions that did not change the legal framework for the regulatory impact assessment, but introduced some new measures, mechanisms and procedures. Since 2009 the Federal Government, in cooperation with Länder, the Federal Statistical Office, and the NRCC, has conducted a series of ad hoc studies aimed at reducing administrative burdens and compliance costs in various areas.17x The list of annual reports of the Federal Government and project reports is available at: http://www.bundesregierung.de/Webs/Breg/DE/Themen/Buerokratieabbau/2012-06-22-projektbericht.html. After having achieved the bureaucracy reduction target of 25 per cent in 2013, a new objective has not been set. Measures to hold administrative costs and compliance costs stable were the introduction of the bureaucracy-cost index (Bürokratiekostenindex18x The bureaucracy cost index with base date 1 January 2012 tracks the bureaucracy costs from information obligations for businesses. It is available at: www.destatis.de/DE/ZahlenFakten/Indikatoren/Buerokratiekosten/Ergebnisse/Buerokratiekostenindex/Buerokratiekostenindex.html. ), the Monitor-Erfüllungsaufwand19x The Monitor-Erfüllungsaufwand was introduced in July 2011 tracking the development of compliance costs for the addressees for each new regulatory proposal. It is available at: http://www.normenkontrollrat.bund.de/Webs/NKR/Content/DE/Artikel/monitor_ea_ausfuehrlicher_text.html (Monitor compliance costs) and a “one-in, one-out” rule. One of the decisions taken in early 2013 was to introduce an evaluation procedure for regulatory proposals after entry into force (based on a decision of the state secretaries responsible for reduction of bureaucracy).20x The decision provides for an evaluation of regulatory proposals 3-5 years after entry into force. Another decision was the adoption of a “one-in, one-out” rule for compliance costs of businesses, similar to the rule in the United Kingdom. The rule applies to new regulatory proposals from January 2015 onward.21x First, the rule should apply to all regulatory proposals from 1 July 2015. The state secretaries responsible for reduction of bureaucracy decided in early 2016 to set the starting date on 1 January 2015. See https://www.bundesregierung.de/Content/DE/Artikel/Buerokratieabbau/Anlagen/15-03-25-one-in-one-out.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=3 Moreover, the NRCC financed some studies dealing with the quantification of benefits of regulations, ex post evaluations practices, and the opportunities to better involve different federal actors.22x The studies are available at: https://www.normenkontrollrat.bund.de/Webs/NKR/DE/Service/Publikationen/Gutachten/_node.html In 2015, for the first time systematic surveys for citizens and businesses about the perceived bureaucratic burden in different, but typical situations of life were conducted.23x Information can be found at: https://www.normenkontrollrat.bund.de/Webs/NKR/DE/Service/Publikationen/Gutachten/_node.html The database maintained by the Federal Statistical Office on (substantive) requirements and information obligations contains more than 17,500 data entries for citizens and businesses from existing legislation.24x The database on information obligations and substantive legal requirements is available at: http://www.destatis.de/webskm. As of 10 March 2014, it contains a total of 17,650 requirements, 14,400 information obligations for business, 637 substantive requirements for businesses, and 2,613 requirements for citizens.

This indicates that apart from the institutionalized system for regulatory impact assessment, there are a number of initiatives by the Federal Government and other actors in the area of better regulation that have paved the way for the extension of the institutionalized system in the past.3.2 Overview of the current system

The basis of the better regulation system is the Joint Rules of Procedure of the Federal Ministries (GGO).25x Latest version of GGO dates 5 October 2011. The GGO regulates the principles of organization of the federal ministries, the cooperation between federal ministries and with constitutional bodies, as well as the external course of business. It contains rules and provisions for the process of “drafting of laws” in chapter 6: preparation of Federal Government Bills (section 1), structuring Federal Government Bills (section 2), involvement and information (section 3). Paragraph 44 GGO is the most relevant for the analysis as it outlines the areas of Gesetzesfolgen (regulatory impacts). The GGO applies only to legislative proposals from the Federal Government. Its rules do not cover legislative proposals brought into the Parliament by political parties represented in the Bundestag (“from the floor of the Bundestag”), or those proposals brought in from the Länder (German states). Legislative proposals prepared by the Federal Government represent the large majority of laws in Germany by number. The Länder, which also have some lawmaking competencies in various areas,26x See Helge Sodan & Jan Ziekow, Grundkurs öffentliches Recht, 136 (2012) for an overview. See also section VI Basic Law on federal legislation and legislative procedures. have partly put in place procedures for lawmaking within their realms, which, however, are not as comprehensive as the procedures put in place at the federal level.

The second basis for better regulation instruments at the federal level is the Act on the Establishment of the NRCC of 14 August 2006, which was amended on 16 March 2011.27x Gesetz zur Einrichtung eines Nationalen Normenkontrollrates [NKRG]. Moreover, there are several guidelines provided by ministries on various aspects of lawmaking and on regulatory impacts.28x This encompasses the handbook for preparation of legal and administrative ordinances of the Federal Ministry of the Interior (Bundesministerium des Innern (ed.): Handbuch zur Vorbereitung von Rechts- und Verwaltungsvorschriften) (2012), the handbook on formal requirements for drafting legislation and on the examination of legislation in accordance with systematic and legal scrutiny of the Federal Ministry of Justice, the guidelines of the Federal Ministry of Finance on how to determine the fiscal impact of a draft law (Bundesministerium der Finanzen (ed.) (Federal Ministry of Finance), Allgemeine Vorgaben des Bundesministeriums der Finanzen für die Darstellung der Auswirkungen von Gesetzgebungsvorhaben auf Einnahmen und Ausgaben der öffentlichen Haushalte (2006)), the guidelines on the methodology of measuring administrative burdens (Bundesregierung (ed.) (Federal Government), Einführung des Standardkosten-Modells - Methodenhandbuch der Bundesregierung (2006)) and on compliance costs (Bundesregierung (ed.), Guidelines on the Identification and Presentation of Compliance Costs on Legislative Proposals by the Federal Government (2012)), and the guidelines on gender mainstreaming (Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend (ed.), Arbeitshilfe zu § 2 GGO: Gender Mainstreaming bei der Vorbereitung von Rechtsvorschriften (2005)).3.2.1 Main actors in the area of better regulation

a) Actors according to the GGO

The GGO sets out a number of rules on the involvement of stakeholders in the process of drafting federal legislation. The main actor is the responsible (lead) ministry in whose sphere of competence the legislative proposal falls.

If a legislative proposal is prepared, the office of the chancellor needs to be permanently informed about the current status of preparation and the time plan for the legislative procedure. Moreover, when legislative proposals concern Länder and municipalities, Länder and the municipal associations represented at the federal level need to be given an opportunity to provide a statement before drafting.

In addition, a number of participation rules apply to further stakeholders within the Federal Government. The responsible ministry has to involve the ministries affected by the legislative proposal as well as the NRCC in the process of preparing and elaborating the legislation at an early stage. Also, the Ministry of Justice and the Ministry for the Interior have to be involved. They examine legislative proposals for compatibility with the Grundgesetz (Basic Law). In case the legislative proposal needs a verification of compliance with the European law, the ministries with competences in matters of European law have to be involved.29x This is, in most cases, the Ministry for Economic Affairs. If the NRCC issues a statement, the responsible ministries have to examine whether a statement of the Federal Government in response is necessary. Finally, the Bundesbeauftragte für Wirtschaftlichkeit in der Verwaltung (National Performance Commissioner) has to be involved.30x The task of the Bundesbeauftragter für Wirtschaftlichkeit in der Verwaltung (Federal Performance Commissioner) is to put forward proposals, recommendations, reports, and opinions in order to enhance the efficiency of and, accordingly, organize the federal administration, including its off-budget and trading funds. The office of the Federal Performance Commissioner is held by the President of the Bundesrechnungshof (Federal Court of Auditors).

Before a legislative proposal is brought forward to a decision in the Federal Government, it has to be submitted to the Ministry of Justice for an examination of its systematic logic and the principles of legal logic. Furthermore, the legislative proposals must be passed to the Länder, municipal associations and the representation of the Länder at the Federation at an early stage, if their interests are concerned. The same is valid for expert groups and confederations. If a public hearing is made, the municipal associations have to be invited.b) National Regulatory Control Council

The establishment (appointment) of an independent body in the form of the NRCC in September 2006 represented the main change of the system of better regulation. Meanwhile, it turned into a dominant actor.31x Vgl. Sylvia Veit & Markus Heindl, 2013, Politikberatung im Spannungsfeld zwischen Unabhängigkeit und Relevanz: Der Nationale Normenkontrollrat, Zeitschrift für Politikberatung (ZPB), p. 111-124. It is one of the established “regulatory watchdog” institutions that can also be found in other countries like the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Sweden or the Czech Republic. Since 2011 the NRCC has consisted of 10 members (it was 8 members before), who are appointed for five years. A secretariat at the chancellery was established with a staff of 15 people.

The tasks and duties of the NRCC are determined in the Act on the Establishment of the NRCC. It provides assistance to the Federal Government by implementing its measures concerning bureaucracy reduction and better regulation. The NRCC examines the description of the compliance costs arising from new regulations for citizens, businesses, and public administration in terms of comprehensibility, correct methodology, as well as the description of further costs for businesses, in particular for medium-sized enterprises. Its right to examine extends to drafts of new federal laws, drafts of subordinated executive orders, and administrative orders, and the work in preparation for statutory instruments of the European Union and for regulations, directives, and decisions of the European Union. In the case of implementation of EU law, it has the right to examine the relevant acts and subordinate legal and administrative provisions. Finally, it can review existing federal acts, and ordinances and administrative provisions based on them.

The mandate of the NRCC was significantly expanded after the 2011 reform. The scope of its assistance was expanded from the initial application, observation, and further development of standardized measurements of administrative costs (old version of the Act of the Establishment of the NRCC) to all measures undertaken by the government in the area of bureaucracy reduction and better regulation. The most significant change was the shift from the determination of bureaucracy costs to the determination of compliance costs of federal legislation for the addressees: citizens, businesses, and public administration. Since 2011, the scope of the NRCC’s review rights involves not only the ministries’ estimates of consequential costs for citizens, businesses, and public authorities, but also “information concerning the aim and necessity of any regulation for its comprehensibility, considerations relating to other possible solutions, considerations regarding the effective date of a regulation, time limits and evaluation, information concerning simplifications of legal and administrative procedures and information on the one-to-one transposition of EU law.”32x See overview of NRCC tasks, available at: https://www.normenkontrollrat.bund.de/Webs/NKR/EN/Overview_of_Tasks/Ex_ante_Review/_node.html The review right of the NRCC today encompasses 6 out of 12 areas to be specified in the explanatory memorandum of legislative proposals. Before 2011, it only scrutinized the estimates of bureaucracy costs. Moreover, the NRCC does not only scrutinize legislative proposals of the Federal Government, but also proposals brought in from the Bundesrat or the floor of the Bundestag if submitted.

The 2011 reform of the act brought more comprehensive reporting duties for the Federal Government, in particular on the achievements and developments in the area of better regulation. Moreover, for the first time, the tasks and functions of the Statistisches Bundesamt (Federal Statistical Office) resulting from the act were defined in its 2011 revision. The NRCC comments on the yearly Federal Government report.3.2.2 Areas of impact analysis

a) Overview

The Joint Rules of Procedure of the Federal Ministries (GGO) were refined several times and in many ways. It provides an extensive list of statements to be provided in the explanatory memorandum setting out the reasons for the legislative proposal.

Tabel 2: Elements of the explanatory memorandum according to paragraph 43 GGO33x Official translation provided by the Federal Ministry of the Interior, available at: http://www.bmi.bund.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/EN/Broschueren/Joint_Rules_of_Procedure_of_the_Federal_Id_23338_en.pdf?__blob=publicationFile.1. The purpose and necessity of the bill and its individual provisions; 2. The matters of fact underlying the bill, and the findings on which it is based; 3. Whether there are other possible solutions, and whether the task can be performed by private parties, and what considerations led to their being rejected, as the case may be; 4. Whether duties of disclosure, other administrative obligations or reservations on the granting of permission are being introduced or extended together with corresponding government monitoring and permission procedures, and what grounds argue against replacing them by a self-obligation of the addressee of the legal norm;. 5. The regulatory impacts (paragraph 44); 6. Considerations regarding the effective date of a regulation; 7. Whether the bill proposes to simplify the law and administrative procedures, and in particular whether it simplifies or supersedes current regulations; 8. Whether the bill is compatible with the law of the European Union; 9. Whether in case of EU law implementation, it goes beyond the provisions of EU law; 10. Whether the draft law is compatible with international law/treaties Germany has concluded; 11. Changes to current legal position; 12. Whether article 72 III or article 84 I Basic Law gives specificities on entry into force and how this was taken into account. The areas highlighted in table 2 are areas that are examined by the NRCC. All legislative proposals contain a statement by the lead ministry to the foregoing issues in the explanatory memorandum to the draft proposal. Point Nr. 5 “Regulatory impact” is further specified in paragraph 44 GGO (table 3). It is particularly relevant as it presents the areas of the regulatory impact analysis.

Tabel 3: Areas of Gesetzesfolgen (regulatory impacts), according to paragraph 44 GGO34x Official translation of the Federal Ministry of the Interior.1. Regulatory impacts mean the main impacts of a law: This covers its intended and unintended side effects. The account of foreseeable regulatory impacts must be drawn up with the respective competent federal ministries, and with regard to the financial implications it must be indicated what the calculations or assumptions are based on. It is to describe whether the impacts correspond to a sustainable development,37 in particular regarding long-term effects. The Federal Ministry of the Interior can issue recommendations for regulatory impact analysis. 2. The impact on the public budgetary income and expenditure (gross) must be presented including the foreseeable impacts resulting from implementation of the law. The Federal Ministry of Finance may issue general instructions on this subject in consultation with the Federal Ministry of the Interior. The income and expenditure accrued to the federal budget must be broken down for the period of the Federation’s multiyear financial planning, stating whether, and if so to what extent, the additional expenditure or reduced revenues are taken into account in the multiyear financial planning, and how they can be compensated for. It may become necessary to calculate, or even estimate, the sums in consultation with the Federal Ministry of Finance. If there are no financial impacts, this must be stated in the explanatory memorandum. 3. Any impacts on the budgets of the Länder and local authorities must be stated separately. The lead federal ministry responsible for the bill must obtain details of expenditure from the Länder and national associations of local authorities in good time. 4. Compliance costs for citizens, businesses and administration. 5. Details must be given, in consultation with the Federal Ministry of Economics and Technology, of: the costs to industry and to small and medium-sized enterprises and the impacts of the law on unit prices, price levels in general and its effects on the consumer.

Impact on consumers in consultation with the Ministry for nutrition, agriculture and consumer protection.

6. Upon request of an interested party, under paragraph 45 (1) – (3), details must be given of any further impacts that this party expects. 7. In the explanatory memorandum for the bill, the lead federal ministry must state whether, and, if so, after what period of time, a review is to be held to verify whether the intended effects have been achieved, whether the costs incurred are reasonably proportionate to the results and what side effects have arisen. Introduced in the context of GGO revision of 1 June 2009.

Even if not listed in the preceding paragraphs referred to, paragraph 2 GGO provides additionally for equality between men and women as a guiding principle for all political, legislative, and administrative actions.35x To this end the Bundesministerium für Familien, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend (Federal Ministry for Families, Seniors, Women and Youth) has developed a guideline on gender mainstreaming „Arbeitshilfe Geschlechterdifferenzierte Gesetzesfolgenabschätzung – Gender Mainstreaming bei der Vorbereitung von Rechtsvorschriften“.

b) The concept of compliance costs

At the center of attention was in the last years and still is the shift from bureaucracy costs to compliance costs in the ex ante assessment of legislation proposals. The adopted concept is a further development of the standard cost model.

According to its definition in paragraph 2 of the Act on the Establishment of the NRCC, “compliance costs include the measurable time expenditure and the costs incurred by citizens, business and public authorities36x Part of the compliance costs are costs not only of the federal administration, but also of authorities of the Länder. The latter are, in most cases, responsible for the execution of federal laws. in order to comply with federal regulations.”37x Compliance costs do not include taxes, social security contributions, and budget lines administered by the Länder. Indirect effects such as lost profits and other charges are also not regarded. Administrative costs or bureaucracy costs stem from information obligations and form part of compliance costs. “Obligations are individual provisions which lead directly to a change in costs, time expenditure or both for its addressees.” They “are the result of federal legislative acts. They oblige addressees to comply with certain objectives or orders, or to refrain from certain actions. They may also demand cooperation with third parties or to monitor and control conditions, actions, figures or types of behavior. Information obligations form a subgroup of obligations so defined.”38x Bundesregierung, Guidelines regarding the identification and presentation of compliance costs, (2012), p. 8. “Information obligations are all obligations according to which data and other information has to be procured and kept available for authorities or third parties, or communicated to them.”39x Id. Information obligations include, for instance, “obligations to complete applications and forms, to participate in official surveys, or to provide supporting evidence and documentation (information, reporting, publication, registration, approval, etc.).”40x Paragraph 2 (2), Sentence 2 of the Act in the Establishment of the National Regulatory Control Council. “Direct” means that the change in costs or time expenditure is directly connected to the compliance with a particular legal provision. Examples of compliance with obligations in contrast to information obligations are, for instance, the maintenance of machinery, the provision of protective equipment, or costs for identifying and processing information. The concept of compliance costs is therefore much broader than the earlier focus on bureaucracy costs from information obligations.

The ex ante assessment of compliance costs involves identifying obligations and identifying the change in compliance costs (identifying the number of cases per obligation or process, identifying the change in compliance costs per change, and identifying the total change in compliance costs) and the presentation of the overall results.41x Those steps apply for the assessment of compliance costs for all addressees. Examples for the determination of compliance costs for citizens, businesses, and public administration that have some differences are provided in the “Guidelines regarding the identification and presentation of compliance costs” from page 13 onward. If addressees can comply with obligations or processes42x Processes are several obligations that are in practice fulfilled in one step and that can be combined or clustered. in very different ways, it might imply larger differences in compliance costs, so that case groups can be formed.43x For instance, the conversion of existing plants versus the replacement of old plants by new plants can be considered as two different case groups. For each case group the compliance costs are separately identified and described. -

4 Challenges for the better regulation system emerging from Germany’s federal structure

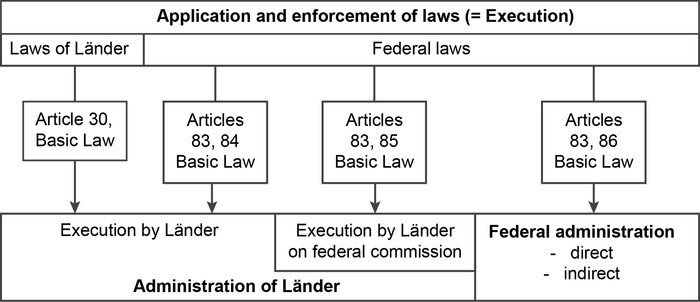

An important issue to consider when investigating the German system is the division of legislative power at the federal level, and the execution of federal laws by the Länder in most cases (figure 1). This brings some challenges for the regulatory impact assessment as these laws are assessed ex ante at the federal level, but executed at the level of the Länder, which have the right to make crucial implementation choices.

Administrative competence according to Basic Law (Source: Sodan and Ziekow (2012))

The Länder’s strong constitutional position has a major influence on how laws are implemented and executed. This is provided for in Article 83, which states: “The Länder shall execute federal laws in their own right as this Basic Law does not otherwise provide or permit.” This involves, according to article 84 Basic Law, that in case the Länder execute federal laws in their own right (as a “matter of own concern”), they shall provide for the establishment of the requisite authorities and regulate their administrative procedures. In practice, this applies to the majority of federal laws, so that the main model of execution is “execution by the Länder.” Even if the execution by the Länder takes place under federal oversight, in practice an effective oversight of the execution by the responsible federal ministry is not ensured, according to the evidence of the National Performance Commissioner.44x See Bundesrechnungshof, Bemerkungen 2012, p. 125-128.

Other types of execution – “execution by the Länder on federal commission (Article 85)” and “federal administration (Article 86)” – apply only to a few areas. The first type applies, for instance, to the so-called Geldleistungsgesetze according to article 104a Basic Law, where the Länder execute federal laws in their own right, which provide for money grants to be administered by the Länder. Those federal laws may provide that the Federation shall pay for such grants either completely or partially. For example, the federal laws for Wohngeld45x Wohngeldgesetz (WoGG). (housing benefit), Elterngeld (parental allowance), and BAföG (student funding under the Federal Education and Training Assistance Act provide that the Federation shall finance one half or more of the expenditure. If this is the case for a given law, this law is executed by the Länder on federal commission. Examples of matters of federal administration, where the Federation executes laws through its own administrative authorities, are the foreign service, the federal financial administration, the administration of federal waterways and shipping, air transport administration, or rail transport administration.46x The areas or matters where laws are executed by federal administrative authorities, or by federal corporations or institutions established under federal law, are defined in articles 87a-87e Basic Law.

If a law is executed by the Länder on federal commission, the Federation has some rights that go beyond the cases where the Länder execute federal laws not on federal commission. The additional rights involve the right to issue general administrative rules with the consent of the Bundesrat. Furthermore, the authorities of the Länder are subject to instructions from the competent highest federal authorities, which are the federal ministries responsible for the policy area. In this respect, oversight applies to the executing Länder authorities as if they were federal authorities. Moreover, federal oversight extends to legality of the enforcement, appropriateness and expediency of execution, whereas, in the case of Länder administration (not on federal commission), oversight is to ensure that the Länder execute federal laws in accordance with the law (legality of the enforcement).

The separation, for most laws, of lawmaking and execution is the reason why the German style of federalism is often referred to as executive federalism, where laws are made on the federal level (with the participation of the Länder in the Bundesrat), but not executed by federal authorities, but by the authorities of the Länder (or local authorities). A major challenge for the governance of better regulation is the fact that the actors mainly concerned with the execution of laws are not well represented in the better regulation system. At the federal level, there is often insufficient knowledge of how laws are executed in detail at the level of the Länder, since there is not yet a systematic approach for ex post evaluation. This leaves a lack of information for those actors involved in the lawmaking exercise and in the regulatory impact assessment.A rule’s life in German executive federalism

By institutional design the rule’s life of a given federal regulation in Germany in the regular case is split into activities that fall under different responsibilities. The first phases, preparation and adoption, of the rule’s life lie within the responsibility of the Federal Government, whereas the last phases, implementation and application/execution, are within the competence of the Länder. This also involves the production of secondary legislation as part of the Länder’s responsibility. The Länder may further delegate the responsibilities for implementation and application/execution to the authorities of counties and municipalities.

This has important implications for the implementation and application of federal laws. Since the Länder execute federal laws in their own right or on federal commission, the implementation and application of laws might differ between the Länder. There could also be differences regarding the impacts, for instance in compliance costs, of federal laws between the Länder. The degree of differences may depend on several factors such as the room a particular federal law leaves to the Länder and responsible authorities to decide on particular cases, the organization and structure of Länder administrations, the secondary legislation adopted by the Länder, and the implemented administrative procedures. Also, the administrative culture might play a role. All this might have impacts on several factors, which have to be addressed in the ex ante assessment of legislative proposals and in the explanatory memorandum.

This complexity arising from the federal structure has important implications for the overall impact of the better regulation system since a systematic feedback mechanism from the executing level to the lawmaking level is not well established. The regulatory impact assessment takes place in the first phase (ex ante) of a rule’s life, but rarely ex post after implementation of the legislation. This leads to a lack of information at the rule-making level and to information asymmetries regarding the actual application and execution of federal laws. -

5 Appraisal of the better regulation system as quality assurance system

This section assesses the better regulation system against the backdrop of the analytical framework and provides some empirical evidence for current weaknesses of the system. The evidence draws on literature reviews, own observations, and empirical findings from a research project that focused on the implementation of federal legislations by subnational units. If the entire system described in the foregoing section is considered as a quality assurance system to ensure better regulation, three factors are of particular importance:

the consequences for the regulatory impact assessment system coming from Germany’s federal structure, providing for a separation of lawmaking and law execution;

the actual degree of compliance with set rules and procedures in the area of better regulation; and

the question of whether the regulatory impact assessment, focusing exclusively on costs, can provide sufficient information in order to contribute to better regulations.

5.1 Underestimated: Differences in execution owing to separation of lawmaking at the federal level and execution of federal laws by Länder

By looking at a rule’s life (figure 2) one can see that the competence for the execution of the law is in the hands of the Länder, even though most of the laws are made at the federal level. However, the regulatory impact assessment assumes that laws are executed in the same way, although empirical evidence suggests differences in the execution of federal laws among the Länder. This is particularly the case if the law allows application and execution in different manners. The separation of rule-making and execution implies that the 16 Länder could take 16 different types of law implementations, yet still be in conformity with the law. This can be true even when laws are executed on federal commission. Although in practice there are numerous meetings of the Länder government officials for various policy areas where the Länder consult on how to harmonize the unified application and execution of federal laws, differences cannot be ruled out.

Empirical evidence for these differences was identified in a number of projects conducted by the NRCC in cooperation with the Federal Government, responsible federal ministries, a number of Länder, and local authorities within the Länder in the years 2009 and 2010.47x See Dirk Zeitz, Bewertung der Einfacher-zu-Projekte unter dem Blickwinkel eines Vollzugsbenchmarking, 76 FÖV Discussion Paper (2013) for a summary on the empirical evidence of the NRCC projects. The projects, titled Einfacher zu… (Facilitating the Application of…), focused on the administrative procedures for granting parental allowance,48x Bundeskanzleramt (German Chancellery), Einfacher-zum-Elterngeld (2010). student funding under the Federal Education and Training Assistance Act,49x Bundeskanzleramt, Einfacher-zum-Studierenden-BAföG (2009). and housing benefit.50x Bundeskanzleramt, Einfacher-zum-Wohngeld (2010). Since all actors participated in the projects, which are either making the law or executing the laws, numerous proposals on how to simplify administrative procedures and reduce the administrative burdens for all addressees (citizens, businesses, and public administration) were developed. These underlying laws are executed by Länder offices (respectively local authorities) on federal commission.

These projects showed, in particular, differences in the required time to handle the submitted requests (application forms) in the public administration. According to the data, the time needed to handle an “average efficient standard case” in the public administration for housing benefit (here for the first request for a direct grant to the rent) reached 38,2 minutes to 178,6 minutes depending on the office, whereas the median was 87,4 minutes. In the case where the request was renewed or a request for a higher grant was made, the working times in the responsible offices ranged from 26,1 to 155,1 minutes (median 68,4 minutes). In both cases the time needed for handling the request was more than five times as long in the office for which the maximum was measured as for the office with the minimum value. However, only 12 offices from four Länder took part in the measurements, and therefore the results are neither significant nor reliable. The spread between the values was unexpectedly large, if one considers that the study was on a federal law that is executed on federal commission. The findings may provide evidence for large differences in the efficiency of execution of federal laws. The qualitative descriptions of working processes showed differences between offices regarding IT systems to process requests or “applications,” regulations for the organization of the data exchange between different offices within the administration, and the division and organization of labor in the office. Differences can also be found when looking at application forms for different social benefits such as housing benefit.51x A detailed comparison of application forms for housing benefit across the Länder can be found in Dirk Zeitz, Der Antrag auf Wohngeld als Beispiel der Konsequenzen des Exekutivföderalismus auf den Erfüllungsaufwand, FÖV Discussion Paper Nr. 80 (2015). Making the design of application forms also falls in the competence of the Länder for the execution of laws. The identified differences in the implementation and execution of federal laws could be an explanatory factor for observed differences in the time required to process applications in the public administration.

The findings were the starting point for a more detailed study on the execution of the law on housing benefit, which was conducted in 2015.52x The complete results of the study will be published in the course of 2016. In total, 201 offices from 11 Länder participated. The results reveal, in particular, differences concerning the use of IT systems: whereas in some Länder there is one solution for all offices in a given Land, there were also Länder in which the offices use different IT systems (up to four different solutions). Some solutions are applied in different Länder. Further differences related to the question of the level at which the offices are located. While most Länder locate the offices at the counties (Landkreise) or county-free cities (kreisfreie Städte) and only larger municipalities, there are also Länder where the task is delegated to the municipalities. Another difference concerns the payment of the housing benefit: is it made decentralized by the office or centralized by a responsible place at the level of a Land? The way administrative procedures are implemented by the Länder could also have direct effects on the compliance costs faced by the addressees, citizens, and businesses in a given Land, but also for the offices. Also, in this study large differences in the time required to process applications between the offices could be identified, but clear recommendations for the design of the execution or the implementation cannot be formulated. The empirical problem faced is to disentangle drivers of compliance costs that may be due to implementation choices from effects that are due to external factors, i.e., factors that cannot be influenced by the offices such as the completeness of applications, the behavior of applicants, etc.

Those differences resulting from Germany’s model of executive federalism and the role of Länder as laboratories for the execution of federal legislation are not fully taken into consideration in the regulatory impact assessment. This applies not only to differences in execution, but also in terms of cost structures of the Länder, for instance because of different salaries of civil servants.53x In 2006, the legal responsibilities for civil servants’ remuneration were shifted to the Länder, so from this perspective also, differences may arise. Considering the constitutional rules on administrative competences, the assumption of a unified execution of laws across all Länder cannot hold: While the legal text of federal legislation is binding for all Länder, the actual implementation and execution can vary between Länder. This can lead to differences in compliance costs. The implementation choices made by executing offices can be seen only if the execution of a law is investigated ex post. The current ex ante approach looks at only the legal text, but leaves out the execution of legislation.5.2 Degree of Compliance

In the past, the degree of compliance with the rules laid down in the GGO was rather low. The reasons were the low legal institutionalization of better regulatory instruments, the practical way the regulatory impact assessment was conducted, and also some practical issues.

Although strengthened over time, the instruments of better regulation are still institutionalized to a low degree in a legal sense. The Joint Rules of Procedures for the Federal Ministries, containing those rules and procedures, are not as binding as a law. They are decided by the cabinet and are binding for the Federal Government, but there would be no consequence respectively sanctions if those rules and procedures were neglected. In contrast, the establishment of the NRCC is based on a law. However, even after the 2011 refinement of the law, its review rights or right to scrutinize ex ante impact assessments are referring only to some issues to be provided in the explanatory memorandum of a legislative proposal. The consequence of a poorly conducted or incomplete regulatory impact assessment of the lead federal ministry would be a rather negative statement on the legislative proposal, i.e., bad publicity. However, if the Federal Government wanted to avoid having negative statements by the NRCC on its legislative proposals, the ruling parties could bring in the legislative proposals from the floor of the Bundestag. Then the proposal would not be scrutinized, if not submitted. This presents a loophole in the system that could be exploited to make also legislative proposals pass without having a statement of the NRCC.

In general, the reform efforts may have some positive effects since the impact assessment of legislative proposals takes place behind closed doors within the ministerial administration. Regulatory impact assessment, therefore, was and still is mainly an insider issue.54x Götz Konzendorf, Institutionelle Einbettung der Evaluationsfunktion in Politik und Verwaltung in Deutschland, in Evaluation. Ein systematisches Handbuch, 27 (Thomas Widmer, Wolfgang Beywl & Carlo Fabian eds. 2009). Even though the GGO foresees consultations with different stakeholders on the draft proposals, and in fact those consultations take place, who the stakeholders were that participated in the process is not disclosed. The higher degree of transparency could to some extent relieve some problems relating to the self-interests of the Federal Government and government officials or civil servants working in the relevant area. The officials within government have an interest in agreeing to the necessity of their own proposed regulation and would tend to underestimate costs while overestimating benefits. Because of the stronger weight those concerned with drafting the proposals lay on political rationalities – pushing through the legislation – rather than factual rationalities, the idea of achieving rational decisions on political matters through checklists and methods of analysis was assessed to be far from reality.55x Renate Mayntz, Gesetzgebung und Bürokratisierung. Wissenschaftliche Auswertung der Anhörung zu Ursachen einer Bürokratisierung in der öffentlichen Verwaltung (1980). However, the need to create greater transparency of the costs of regulations (for addressees), also in the political decision-making process, and to make them an integral part of the discussion on regulations was finally taken up in the context of the introduction of the standard cost model and the concept of compliance costs.

Another issue in the practical conductance of impact assessments was and still is the lack of empirical knowledge and high measurement uncertainty of regulatory impacts. Other reasons for a low degree of compliance with the GGO rules are the lack of specialization and the lack of experience of those people conducting impact assessments. The federal ministries, where staff was reduced over decades, just suffer from a lack of resources to carry out comprehensive impact assessment or cost-benefit analysis within the often very strict time schedules. Konzendorf cited further reasons why the system in practice does not function as it should.56x For instance, a lack of guidelines, practical examples, and institutional support sanctions, see Götz Konzendorf, Gesetzesfolgenabschätzung, in: Handbuch zur Verwaltungsreform, 135 (Bernhard Blanke, Frank Nullmeier, Christoph Reichard & Göttrik Wever eds., 2011). His main line of argument is that there is a trade-off: while regulatory impact assessment can in fact improve the quality of regulations, in practice, the quality of the regulatory impact assessment depends on the resources (staff, time) made available to conduct them.

This low degree of implementation until the year 2011 can be underpinned with data. Meanwhile, things may have changed to some degree, but so far no studies have been made that cover the development since 2011. Based on draft proposals for the year 2006, Veit found that 94% of legislative proposals contained the statement that there would be no alternative with respect to the proposed regulation. In 53.9 % of the draft proposals it was stated that the regulation would not have any impact on public budgets, and 89 % of the draft laws did not have a statement on whether the law could be determined. Less than 10 % of legislative proposals contained information if an (ex post) evaluation was foreseen. Draft legislation prepared by the Federal Ministry for the Environment foresaw in around 30% of the proposals an evaluation that is a relatively high percentage. Another comprehensive study on the preparation of draft laws of the Federal Government during the period 2004-2008 conducted by the Federal Performance Commissioner found similar results.57x Bundesbeauftragter für Wirtschaftlichkeit in der Verwaltung, Gutachten über Maßnahmen zur Verbesserung der Rechtsetzung und der Pflege des Normenbestandes (2010). Information on a possible delimitation of the law was found in just one fifth of the 690 draft proposals. The issue “evaluation” was addressed only in 6% to 23% of the proposals depending on the policy area. These findings indicate a “striking gap between formal and actual compliance” with regard to the application of regulatory impact assessment.58x See Veit (note 14).

The Federal Performance Commissioner attributed the deficits in compliance mainly to the insufficient legal base of the better regulation instruments set out in the GGO, which is based on the decision of the cabinet, and even if binding for Federal Government without consequences, if it was neglected: “[T]he low degree of legal implementation could be a reason why the procedure does not find the reputation and attention in the ministerial administration, it would deserve.” The Federal Performance Commissioner recommended an improvement of the rules for the evaluation of impact assessments and the establishment of a specific place/office that checks and examines the implementation of the rules regarding the preparation of legislative proposals. This criticism has been partly taken up in the 2011 reform of the Act on the Establishment of the NRCC. The expansion of the mandate of the NRCC can be assessed as a reaction to the government’s low degree of compliance with its rules for regulatory impact assessments. The expansion of NRCC’s mandate may make it more difficult to pass legislative proposals with low quality or incomplete impact assessments without having publicity. So far no studies have been undertaken on how compliance has developed since 2011, but there are reasons to be optimistic:

The share of legislative proposals that contained the category “bureaucracy costs” was significantly higher during the period 2007-2009 in comparison with the period 1999-2003.59x Id. This was the area of regulatory impact assessment the NRCC has had to review since 2006.

Since the number of areas the NRCC reviews expanded in 2011, it is likely that the quality of impact assessment and compliance will improve and that the gap between formal and effective compliance will be reduced.5.3 Just costs without benefits? Conceptual problems with the German cost concept

The German ex ante impact assessment has relied on the concept of compliance costs since 2011. Before that, just the bureaucracy costs from information obligations were examined. In this chapter the specific characteristics of the concept of compliance costs are investigated. General criticism on the standard cost model is found in a number of references.60x See, for instance, Wolfgang Weigel, The Standard Cost Model - A Critical Appraisal, 25th Annual Conference of the European Association of Law and Economics (2008). Radaelli (note 5), Renda et al. (note 11).

Generally, the ex ante assessment in Germany does not quantify the benefits of regulation. The approach, however, may provide reductions in compliance costs through the introduction of new regulations. But showing higher/lower compliance costs without showing some net benefits of regulations leaves the entire ex ante assessment still a one-sided approach. Benefits of regulations are not provided, but only costs of implementing a proposed legislation.61x The German model covers all direct costs except direct charges, taxes, levies, social security contributions, and other direct costs. Also, hassle costs are excluded. Some authors argue that the focus on costs is a key feature of the German system.62x See Jann & Jantz (note 14), Jann et al. (note 3), Wegrich (note 9). The assessment of whether benefits of a regulatory proposal outweigh its costs would be made implicitly by the political decision makers. Consequently, the regulatory impact assessment does not question a given regulatory proposal but rather its legal implementation. In practice, alternative modes of implementation and their impact on compliance costs are rarely provided. One can raise doubts as to whether the system then is able to provide sufficient information for evidence-based decision-making. Referring to the introduction of the minimum wage in Germany, it can be questioned whether a value of 8.50 euros is the “right” one to take.63x See Gisela Färber & Dirk Zeitz (2015): Legitimation durch Gesetzesfolgenabschätzung? Möglichkeiten und Grenzen für die Legitimation staatlichen Verwaltungshandelns, der moderne staat, Zeitschrift für Public Policy, Recht und Management 2/2015. By not considering alternative values, the regulatory impact assessment leaves out the fact that different modes of implementation could go along with differences in compliance costs but also with differences in benefits.

However, the shift from measuring bureaucracy costs arising from information obligations to measuring compliance costs from substantive requirements or obligations represents a significant change. Information obligations are textual parts of regulation that require businesses and citizens to make information available to public authorities or third parties. So information obligations are more or less just data requirements. Whereas the standard cost model, focusing on information obligations, was a rather “unpolitical” approach, the measurement of compliance costs is more comprehensive as it represents a broader concept of costs, with its stronger focus on the substantive requirements of regulation. In consequence, there could be further discussion on the substantive provisions of legislation – think of adequate emission limit values or, as mentioned earlier, the adequate level of a minimum wage.

Compliance costs are determined not only for businesses (personnel costs and material costs), but also for citizens (time expenditure and material costs) and public authorities (personnel costs and material costs). While in principle this gives some more information on the consequences of regulatory impact for several stakeholders, it falls short of covering the impact of interaction processes between addressees in the application and execution of laws. In practice, substitution effects involving shifting of compliance costs from one addressee to another could be quite common. The focus on the burdens for a specific addressee is not sufficient when several addressees are involved in the process of law execution. Reducing the burden for one stakeholder could lead to inefficiencies when the entire process would be taken into consideration. But there are problems in empirically investigating this issue. The extent of interaction effects can hardly be analyzed as the burdens of addressees are investigated separately in surveys. While for the determination of compliance costs, businesses and citizens are usually asked how long it took them to comply with “their” requirement, the question to officials in the public administration is how long it takes to handle a “normally efficient case.” Therefore, results are not comparable since the measurements for addressees businesses and citizens rely on individual cases, whereas in public administration they rely on an average case. However, the individual compliance costs of businesses and citizens may be driven mainly by their individual situation (such as the complexity of the case). Additionally, from the perspective of the executing authorities, a large share of compliance costs is due to external factors such as the behavior of the addressees of a regulation. Some assumptions taken in the ex ante assessment such as the completeness of application forms are rarely fulfilled in practice but can have a significant impact on compliance costs and require additional (unnecessary) interactions between addressees, leading to higher compliance costs.64x In the survey, around 80% of offices for housing benefit said the share of incomplete applications is “high” or “very high”.

Even though the ex ante cost estimates are verified two years after the entry into force of a regulatory proposal, a further problem relates to the doubts on the accuracy of the estimates. As it is the case for the standard cost model, if measurements of compliance costs were repeated, rarely would the same results be obtained, owing to sample bias. In order to better link ex ante and ex post assessment, the state secretaries responsible for reduction of bureaucracy at the federal level and the Länder decided, in January 2013, to establish a broader and systematic ex post assessment for all regulatory proposals adopted with compliance costs larger than one million euro, which should take place three to five years after entry into force. First evaluation reports are expected in 2016, and it remains to be seen which results can be drawn. -

6 Conclusion

The changed perception of better regulation can be seen in the development of the German system of better regulation. This reflects different and partly new demands in terms of today’s criteria for the quality of regulations such as legitimacy, improved transparency in the law making process, and efficiency of law execution. Germany reacted to this changed environment by strengthening better regulation instruments and its regulatory impact assessment by improving governance through the establishment of the NRCC as a ‘regulatory watchdog’, and by adapting the methodology of the ex ante impact assessment.

However, when the system of better regulation is assessed as a quality assurance system along the entire life of a rule and the regulatory cycle, a number of issues leave it incomplete and offer chances for improvements. Three issues that are and seem to remain critical for its performance have been addressed in this article: the extent to which Germany’s federal structure is considered in the better regulation system, the degree of compliance, and the areas of the regulatory impact assessment (in particular on the compliance costs arising from regulation). One can summarize:

The basic assumption of the ex ante assessment that there is a unified execution of federal laws by the Länder cannot be held on the basis of the constitutional provisions of the Basic Law. The reason is the strong constitutional position of the Länder, which are responsible for the execution and the enforcement of federal laws. The Federation has relatively weak means to manage or influence the execution or the enforcement of laws. This leads not only in theory to a variance in the execution of laws among the Länder but also in practice, as empirical evidence suggests. This is closely linked to the differences in the efficiency and efficacy of execution, which could have some drawbacks relating to the impact of the regulation. Since no systematic approach for ex post evaluation yet exists, the experiences and informational advantages of the law-executing actors are underexploited.65x The decision regarding how to evaluate has been left to the federal ministries in charge for a given regulation. So far only a number of pilot studies have been carried out. The system does not make use of the advantages of the federal system, where the Länder serve as “laboratories for the execution of federal legislation”. A stronger involvement of the federal levels responsible for the actual implementation and application of federal legislation could strengthen the regulatory impact assessment, not only in the ex ante phase but also in the ex post phase of the regulatory cycle.

Even though strengthened over time through the 2011 reform of the Act on the Establishment of the NRCC, the degree of institutionalization of the better regulation can still be considered as being rather weak.66x Sabine Kuhlmann & Sylvia Veit, 2013, Der Nationale Normenkontrollrat in Deutschland: Promoter für bessere Rechtsetzung?, Journal of Legislative Evaluation, 10/2013, S. 51-73. One has to remember that the GGO is not as binding as a law and that there are no sanctions foreseen when the rules are neglected. The review rights of the NRCC still cover only legislative proposals of the Federal Government (which could also bring in such proposals via the Bundestag). Also, the difference between formal and factual compliance with the rules and procedures may be still an issue. However, improvements in terms of compliance could be expected from the measures taken, in particular the expansion of the NRCC’s mandate to scrutinize more areas of the impact assessment and the resulting higher degree of transparency. An evaluation procedure for regulatory proposals has been introduced recently, but it remains to be seen what the evaluation reports to be prepared by the lead ministries will look like, which methodology will be applied in the evaluations, and how the Länder as the ones finally executing and implementing the large share of federal legislation will be involved.

The almost exclusive focus on the costs of regulation without specifying any benefits leaves the German system a one-sided approach. This has an impact, in particular, if there are alternative options of rule-making for which different compliance costs have been measured, but which also could have differences with regard to the benefits. This does not provide a sufficient information base to decide on the right policy. Moreover, the strong focus on the compliance costs from substantive requirements for specific addressees such as businesses neglects the complex interaction processes between addressees. This could lead to inefficient substitution effects, where compliance costs are just rolled over from one addressee to another, but in total no reduction of compliance costs is achieved. Finally, the compliance cost approach based on the legal provisions leaves out important drivers of compliance costs from the perspective of executing authorities such as complexity and interaction costs.

In conclusion, even though some gaps can still be identified in the overall approach for regulatory impact assessment along the life of a rule, the reforms of recent years have improved the overall governance of better regulation in Germany as a quality assurance system. The basis of information provided by regulatory impact assessments to take better government decisions and to finally design “better regulations” has been broadened. But there is room for further improvement and the completion of the better regulation system. It can be expected that the degree of compliance will improve following the extended mandate of the NRCC. However, the system still has some basic limitations that cannot be overcome without, for example, introducing some way of also quantifying benefits of regulations. Moreover, without a better consideration of the systematic separation of rule-making at the federal level and execution of federal laws by the Länder, the system remains incomplete. The phases of implementation and execution of laws are currently not yet fully embedded in the overall system, which focuses mostly on the ex ante phase (i.e., rule-making), but neglects the ex post phase (i.e., the execution) of the regulatory cycle. So the three factors discussed in this article are closely interrelated. If the benefits of regulation shall not be quantified, an alternative for improvement could be a stronger consideration of the Länder’s experiences in the application and execution of federal legislation as well as the (alternative) implementation choices made by the Länder. This approach, more oriented towards the execution of federal legislation, may also contribute to reductions in compliance costs. Since the Länder’s experiences and implementation choices can barely be identified before entry into force of a regulatory proposal (ex ante), the focus on ex post phase in the overall approach should be strengthened.

Hence, the challenges for the regulatory impact assessment to serve as a quality assurance system could be addressed through stronger involvement of the actors responsible for the execution, as already shown in a number of NRCC projects. This would provide additional information after implementation of the legislation to be used not only horizontally at the executing level to raise efficiency and efficacy of law execution, but also vertically as a systematic feedback mechanism to the lawmaking level. The consequences of the separation of a rule’s life between phases that are made at the federal level and at the level of the Länder, and the resulting information asymmetries, could perhaps be overcome by the introduction of a benchmarking approach targeting the execution of federal legislation (Vollzugsbenchmarking). Thereby a process of mutual learning and a culture more headed towards the evaluation of existing legislation could be promoted. Such an approach could complete the regulatory cycle and improve the information base for decision-making. The “Facilitating the Application of…” projects were very successful and can serve as an example of how this could be realized in practice as they have already implemented this overall approach that takes the multilevel regulatory governance in a rule’s life into consideration. - * Special thanks to two anonymous reviewers and Stephanie Hengstwerth for comments.

-

1 See Andrea Renda, Impact Assessment in the EU: the state of the art and the art of the state, Centre for European Policy Studies (2006); Claudio M. Radaelli, Diffusion without convergence: how political context shapes the adoption of regulatory impact assessment, Journal of European public policy (2005); on the German system in international comparison see Werner Jann, Kai Wegrich & Jan Tiessen, Bürokratisierung und Bürokratieabbau im internationalen Vergleich – wo steht Deutschland? (2007).

-

2 See OECD, Better Regulation in Europe: Germany 2010 (2010) and OECD, Regulatory Policy Outlook 2015 (2015).

-

3 See Claudio M. Radaelli, Measuring policy learning: regulatory impact assessment in Europe, Journal of European Public Policy 16 (8), 1145-1164 (2009) and Claudio M. Radaelli & Fabrizio De Francesco, Regulatory impact assessment, political control and the regulatory state, 4th General Conference of the European Consortium for Political Research (2007).

-

4 See Brownen Morgan, The Economization of Politics: Meta-Regulation as a Form of Nonjudicial Legality, 12 Social & Legal Studies, 489 (2003); Claudio M. Radaelli, Evidence-based policy and political control: what does regulatory impact assessment tell us? Paper for the European Consortium for Political Research Joints Sessions, workshop on “The Politics of Evidence-based Policy Making” (2008).

-

5 See Ortlieb Fliedner, Moderner Staat – moderne Gesetzgebung? Sieben Thesen für bessere Gesetze (2004).

-

6 See Hermann Hill, Recht als Geschäftsmodell – Von Better Regulation zu New Regulation, Die öffentliche Verwaltung (DÖV), 809 (2007).

-

7 See Bastian Jantz & Sylvia Veit, Entbürokratisierung und bessere Rechtsetzung, in Handbuch zur Verwaltungsreform, 126 (Bernhard Blanke, Franz Nullmeier, Christoph Reichard & Göttrik Wever, eds., 2011) and Kai Wegrich, Das Leitbild „Better Regulation": Ziele, Instrumente, Wirkungsweise (2011).

-

8 See Claudio M Radaelli & Anne C.M. Meuwese, Better regulation in Europe: Between Public Management and Regulatory Reform, 87 Public Administration, 639 (2009).

-

9 Andrea Renda, Lorna Schrefler, Giacomo Luchetta & Roberto Zavatta, Assessing the Costs and Benefits of Regulation. Final Report, Study for the European Commission, Secretariat General (2013).

-

10 See Colin Kirkpatrick & David Parker (eds.), Regulatory Impact Assessment: Towards Better Regulation? (2007).

-